Gender Bias May Make Female Hurricanes Deadlier

In both the Bible and magical folklore, power over a man comes from knowing his true name: Speak it and strike him dead. Names carry savage clout in everyday life too, as anyone with parents cruel enough to name them Adolph or Bertha can attest.

Now, a controversial new study suggests gender bias can shape how people respond to hurricane names.

A severe hurricane (category 3 and higher) with a feminine name is more deadly than a storm with a masculine name, behavioral science researchers from the University of Illinois report today (June 2) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). Their statistical model suggests that hurricanes with female names cause nearly three times more deaths than hurricanes with masculine names.

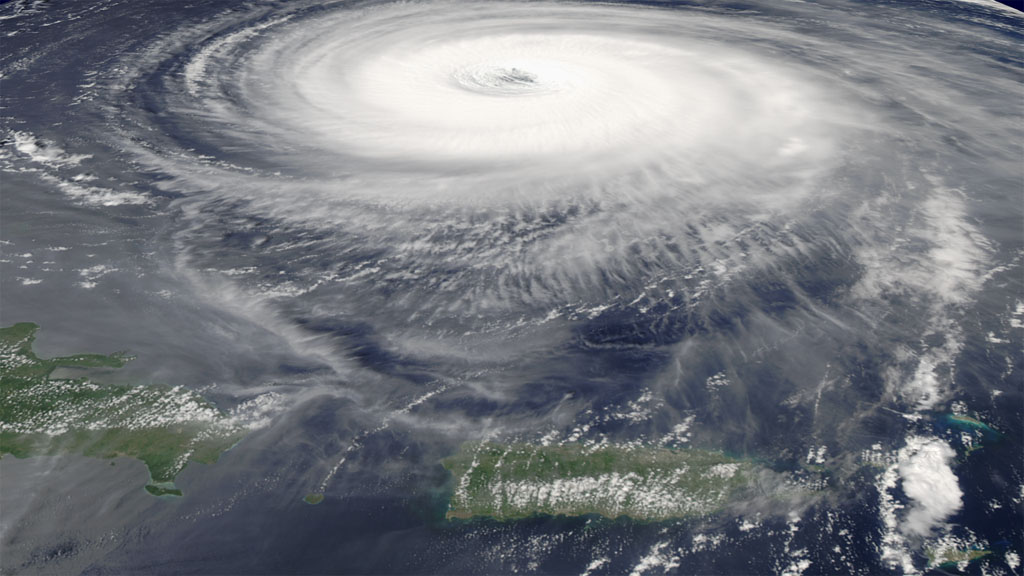

The reason? People perceive storms with female names as less dangerous, don't evacuate and thus die in greater numbers, the researchers think. [Hurricanes from Above: See Images of Nature's Biggest Storms]

"Gender biases and beliefs are very pervasive," said study co-author Sharon Shavitt, a professor and behavioral psychologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. "These kind of biases routinely affect the way we judge people, even when people explicitly say they don't believe that men and women are different."

However, independent researchers found several reasons to question the link between gender stereotypes and hurricane deaths. Here's why.

Findings will spark debate

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings are not surprising to scientists who specialize in the study of names: A deep well of research already shows humans judge others by names, which convey a wealth of information about race, class, age and gender. However, people may be unaware of their underlying prejudices. For example, both male and female science faculty, who are trained to be objective and aware of bias, are more likely to offer jobs to male candidates than to identically qualified women, according to a study published Sept. 24, 2012, in PNAS.

"I think they are absolutely right that names have stereotypes associated with them, and these stereotypes are going to unconsciously affect how easy it is for people to become scared of certain hurricanes," said Cleveland Evans, a professor at Bellevue University in Nebraska and past president of the American Name Society. Evans, who was not involved in the study, said he has written several letters to the National Weather Service to offer advice on naming hurricanes, to no avail. [Sophia's Secret: Tales of the Most Popular Baby Names]

Led by graduate student Kiju Jung, the University of Illinois team studied National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) hurricane names and fatalities for storms that made landfall in the United States between 1950 and 2012. Ranking the storm names from very masculine to very feminine, the researchers discovered the gender effect only came into play for very damaging storms. (The ranking means they can judge each name on its own merits, not male versus female.) There was no gender effect on less-deadly storms, which caused little damage as defined in the statistical model.

"The rigor of the statistical analysis was very strong," Shavitt said.

But disaster expert Hugh Gladwin found the results dubious and misleading. Gladwin pointed out that no simple correlation was found between the number of deaths and male-female hurricane names in the study. "The male-female name predictor is not significant by itself, and only becomes so after a lot of statistical massaging," said Gladwin, an anthropologist at Florida International University in Miami, who was not involved in the study.

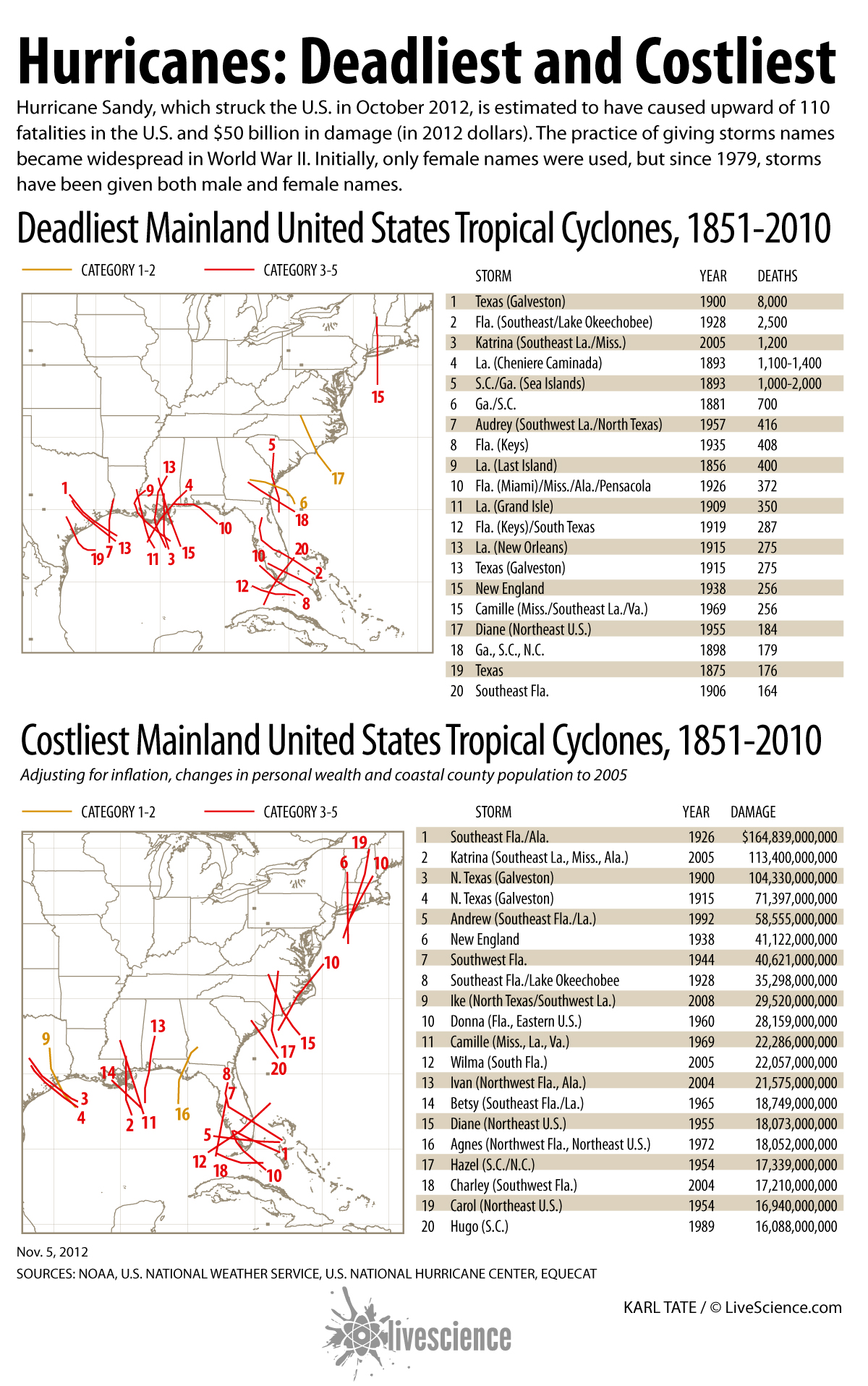

And a Live Science analysis found that since 1979, more male hurricane names have been retired from the official list than female names. The World Meteorological Organization retires names of storms that are particularly damaging and deadly. That means more of the deadliest, costliest storms were named for men: There are 29 retired male-named storms, compared with 24 female storms.

The National Weather Service started naming all Atlantic hurricanes with women's names in 1953. The practice was called sexist in the 1970s, ended in 1978, and the World Meteorological Organization now maintains the official roster. There are six repeating lists, with alternating male and female monikers — one year "A" is a male name: the next it's a female.

On average, hurricanes killed 47 people each year between 1947 and 2013, and 108 people each year between 2004 and 2013 — a jump caused by the incredible number of deaths from Hurricane Katrina, the National Weather Service reports.

Power of prejudice

After accounting for hurricane deaths, Jung and his co-authors asked six groups of participants to imagine being in the path of hurricanes with male or female names. For some groups, the names were similar, such as Victor and Victoria or Alexander and Alexandra. Other groups got names drawn from the official 2014 list, including Omar, Cristobal, Dolly and Bertha. The experimental groups were less likely to evacuate or seek shelter from feminine-sounding storms, and rated these storms as less risky and less intense.

In addition to showing possible gender biases, the experiment in which people were asked to predict hurricane intensity based on actual hurricane names also revealed Americans' deeply held racial and cultural biases, Evans said. On a scale from 1 (least intense) to 7 (very strong), this group ranked Bertha at 4.523, or more intense than four other corresponding male names, except for Omar, at 4.569. Dolly was ranked the lowest.

Since Germany introduced the Big Bertha cannon in World War I, the name Bertha has been connected with fat, loud and obnoxious women, Evans told Live Science. And Dolly reminds people of country signer Dolly Parton, whose friendly reputation colors perceptions of the name, Evans said. Finally, male names with racial or ethnic overtones earned the highest-intensity scores.

"Unfortunately, because of racism, people think anything that sounds black or Hispanic are scary, especially among male names," Evans said. [Understanding the 10 Most Destructive Human Behaviors]

Public health researcher Josh Klapow also sees a problem with extrapolating from focus groups to a real-world disaster setting.

"When you're talking about natural disasters, you can't reproduce many of the psychological elements in a non-disaster setting. A controlled experiment is absolutely contrived," said Klapow, a clinical psychologist at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. "There very well may be differences in the way people interpret names associated with natural disasters, but the whole thing falls dramatically short of changing policy."

Too soon to change names

The experiments with individual groups show that preconceived notions about gender may affect perceptions of risk. But does that mean that hurricanes should be named for flowers, trees and insects, as Asian countries do with Pacific typhoons?

Everyone interviewed for this article said no.

Shavitt hopes the results will correct the potential influence of gender bias by raising awareness. "The power of biases is that they are so under the radar," she said. "I suggest that when the media report about hurricanes, meteorologists avoid using gendered pronouns," Shavitt told Live Science, referring to the way some meteorologists call the male-named storms "he" and female-named ones "she."

And even if female-named hurricanes are deadlier than male-named hurricanes, for practical purposes, names don't matter, Klapow said. "Deadly is deadly."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.