Celebrities, Stooges, and 25th-Century Reporters: Are Video Games Art or Merchandise? (Op-Ed)

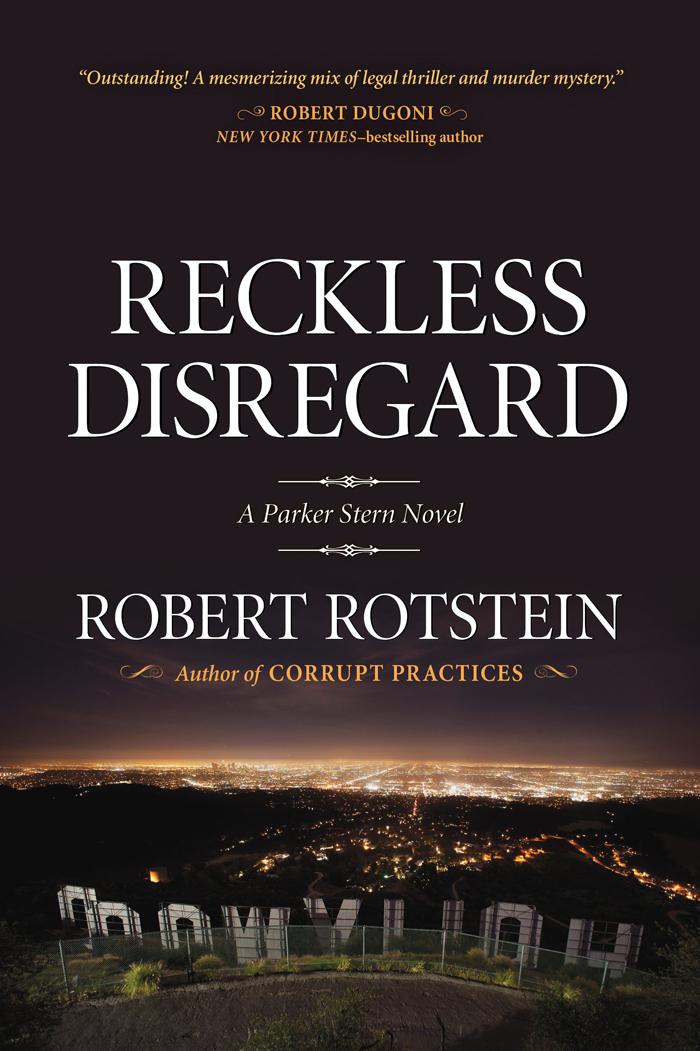

Robert Rotstein is the author of the new novel, "Reckless Disregard" (Seventh Street Books, 2014). An entertainment attorney, he has handled lawsuits on behalf of Michael Jackson, Quincy Jones, Lionel Ritchie, James Cameron, and major motion picture studios, and he has taught as an adjunct professor at Loyola Law School. Robert is currently a partner in a major Los Angeles law firm, where he co-chairs the firm's intellectual property department. He contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Though video games have been around for quite some time, they still have a checkered reputation. They're often accused of causing society's major ills — horrific acts of random violence, childhood obesity, ADHD, creeping illiteracy. The mainstream often dismisses their aesthetic value. The renowned film critic Roger Ebert proclaimed that video games will never be art — meaning that they'll never be as good as movies.

In light of this hostility, it might seem surprising that in a case called Brown v. Entertainment Merchants Association, the Supreme Court of the United States, a staid institution to say the least, decreed that video games are equal to traditional forms of artistic expression: "Like the protected books, plays, and movies that preceded them, video games communicate ideas — and even social messages — through many familiar literary devices (such as characters, dialogue, plot, and music) and through features distinctive to the medium (such as the player's interaction with the virtual world). That suffices to confer First Amendment protection."

So, at least where free speech is concerned, video games are just as worthy as movies and books.

Good news for video-game designers, right? No government censorship, no lawsuits seeking to enjoin the game because of its content? Not so fast. Some troubling recent legal opinions continue to treat video games as second-class forms of expression. These cases involve celebrities who object to the use of their images.

"Hey, Moe, Hey Larry!"

Though their films certainly have a beat 'em up game feel, the Stooges' heyday came decades before video games were invented. Nevertheless, a case involving use of the Stooges' images has had an important impact on the game industry.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

An artist named Gary Saderup sold T-shirts embossed with his charcoal drawing of the Stooges. The Stooges' successors sued Saderup, claiming he'd violated their right to control the commercial use of the Stooges' images (the legal term is "right of publicity"). The issue was whether Saderup's drawings were commercial (if so, the Stooges win) or rather artistic expression (Saderup wins). The California Supreme Court found for the Stooges' heirs, concluding that Saderup's drawings didn't "transform" the Stooges' images — didn't make a significant creative contribution, in other words. The case established the principle that someone can use another's image in an entertainment work only where the use is "transformative." The decision is important because it has been subsequently applied to video games.

Oo la la/Ulala/Gwen Stefani

One of the first video-game cases considering use of a celebrity image involved Sega's Space Channel 5. The game featured a character named Ulala, a twenty-fifth century news reporter with hot-pink hair tied in pigtails. Ulala wore an orange outfit consisting of a midriff-exposing top, a miniskirt, elbow-length gloves and stiletto heels. Not only did Ulala report the news, but she also had some cool dance moves.

Enter singer-dancer Keirin Kirby, who as Lady Miss Kier had fronted an eighties/nineties musical group called Deee-Lite. Kirby claimed that Ulala looked like her, dressed like her, wore her hair like her and danced like her. Worse, Kirby's signature expression had been, "ooh la la." Despite these similarities, the court dismissed Kirby's right of publicity lawsuit, finding that Sega had transformed the character by exaggerating her appearance and making her a reporter in the space during the 25th Century. So far so good for the first-amendment protection of video games.

But things changed when Activision's Band Hero game incorporated images of the band No Doubt performing in unique settings, including outer space. What upset No Doubt was that, supposedly unbeknownst to them, the player could unlock certain levels where the band sang songs they'd never have sung in real life and where lead singer Gwen Stefani sounded like a man.

These departures from reality — an outer-space setting, unusual song choices, a female singer with a male voice — seem quintessentially transformative. Not according to the California appellate court, though, which held that Band Hero did nothing more than depict the band members doing exactly what they do as celebrities — performing songs. The upshot was that Activision had no first-amendment right to depict images of the band in Band Hero.

The problem with this holding is that, if a movie, rather than a video game, had depicted the band in the same way, the result probably would've been different. Twenty years ago, the hit coming-of-age movie "The Sandlot" told the story of a motley group of boys who played sandlot baseball. One of the main characters was "Michael Palledorous," nicknamed "Squints." The real Michael Polydorous, a former childhood friend of the writer, wasn't amused. Apparently, Polydorous as a kid had looked and dressed like the movie character. Even though the Squints character had a similar look and almost identical name to the real person, the court threw the lawsuit out of court because the movie was obviously a fictional work of art entitled to first-amendment protection.

The use of Polydorous's name and likeness in The Sandlot case seems no more artistically expressive than the inclusion of No Doubt in Band Hero. What happened to the principle that movies and video games are equal in the eyes of the law?

"Omaha, Omaha!"

Last year, the prognosis for a designer's ability to use celebrities in video games got even worse. A group of college football players brought a class action against Electronic Arts (EA) and the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) over EA's "NCAA Football." Every real football player had a corresponding avatar with the player's actual jersey number and virtually identical height, weight, build, skin tone, hair color and home state. But these characteristics weren't static. Game players could change the players' abilities and attributes, recruit new players, and control practices, academics and social life. In other words, the video game was interactive, and the gamers could transform the characters. You'd think that, under the Three Stooges case, this ability would mean that the EA's use of the players' images was protected by the First Amendment. Yet, the courts found that EA's depiction of the players wasn't really transformative because the characters were shown doing what they normally do — playing football. The result — in 2013, EA announced that it was discontinuing its football video games. So much for games getting equal treatment with movies and books.

Brown, the very Supreme Court case mandating that video games receive full first-amendment protection, cautioned, "esthetic and moral judgments about art and literature . . . are for the individual to make, not for the Government to decree…" Unfortunately, those courts that have condemned the use of images in video games as "non-transformative" seem to be making aesthetic judgments about the artistic merit of video games. Let's hope such decisions don't stifle the growth of a significant and still developing medium of artistic expression.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.