Cosmic objects with strange orbits discovered beyond Neptune

Are they being tugged by Planet Nine?

A six-year search of space beyond the orbit of Neptune has netted 461 newly discovered objects.

These objects include four that are more than 230 astronomical units (AU) from the sun. (An astronomical unit is the distance from the Earth to the sun, about 93 million miles or 149.6 million kilometers). These extraordinarily distant objects might shed light on Planet Nine, a theoretical, never-observed body that might be hiding in deep space, its gravity affecting the orbits of some of the rocky objects at the solar system's edge.

The new observations come courtesy of the Dark Energy Survey, an effort to map the universe's galactic structure and dark matter that began in 2013. Six years of observation from the Blanco Telescope in Cerro Tololo in Chile yielded a total of 817 confirmed new objects, 461 of which are now being described for the first time in a paper posted on the preprint server arXiv. The paper has been submitted to a journal for peer review, according to ScienceAlert.

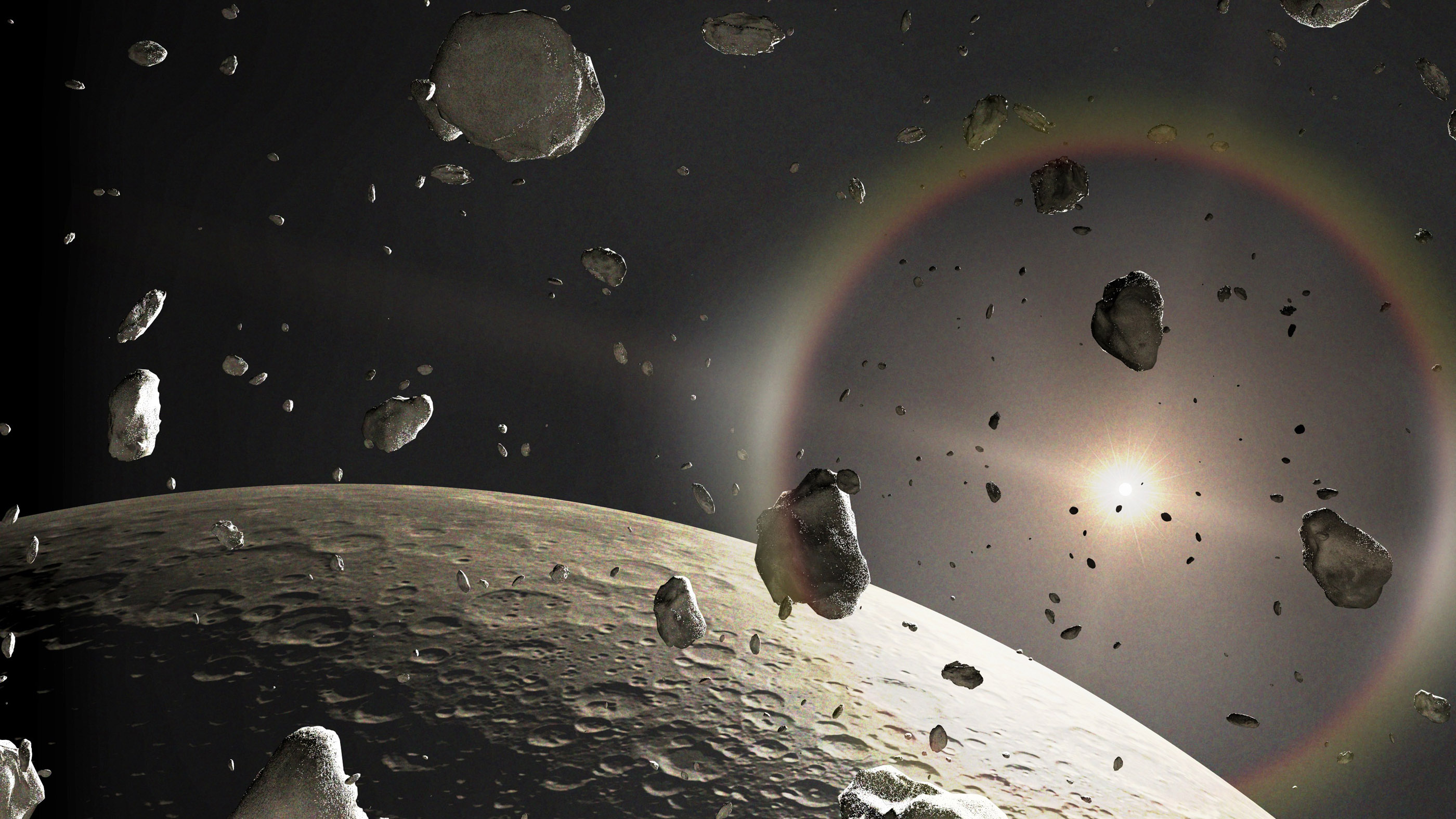

The objects in the study are all at least 30 AU away, in a region of the solar system that is almost unimaginably dark and lonely. More than 3,000 trans-Neptunian objects, or TNOs, have been identified in these icy reaches. They include dwarf planets such as Pluto and Eris as well as small Kuiper Belt objects like Arrokoth, a rocky body visited by the New Horizons spacecraft in 2019. The Kuiper Belt is a region of icy objects orbiting between about 30 AUs and 50 AUs from the sun.

Of the 461 objects described for the first time in the new paper, a few stand out. Nine are known as extreme trans-Neptunian objects, which have orbits that swing out at least 150 AUs from the sun. Four of those are extremely extreme, with orbital distances of 230 AUs. At these distances, the objects are hardly affected by Neptune's gravity, but their strange orbits suggest an influence from outside the solar system. Some researchers think that influence might be a yet-undiscovered planet, dubbed Planet Nine. (Others think that the combined gravity of lots of little objects, or, alternatively, nothing more than a statistical anomaly, explain the weird orbits.) The newly discovered objects could thus help researchers hone in on the possible Planet Nine — or disprove its existence.

The researchers also found four new Neptune Trojans. Trojans are bodies that share the orbits of a planet or moon. In this case, the objects share Neptune's orbit around the sun. They also observed the Bernardinelli-Bernstein comet, named after the two lead authors of the paper, University of Pennsylvania cosmologist Gary Bernstein and University of Washington postdoctoral scholar Pedro Bernardinelli. The two researchers were the first to spot the comet in the Dark Energy Survey dataset. The Bernardinelli-Bernstein comet may be up to 100 miles (160 km) wide. It hails from the Oort cloud, another layer of icy objects even more distant than the Kuiper Belt.

At least 155 of the newly discovered objects are what astronomers called "detached." This means that they are far enough from Neptune that the large planet's gravity doesn't affect them much; instead, they're mostly tied to the solar system by the distant pull of the sun. Detached objects, sometimes known as extended scattered disc objects, tend to have huge elliptical orbits.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings are exciting, the researchers wrote in their paper, because the Dark Energy Survey wasn't meant as a search for trans-Neptunian objects. Its goals were to characterize the theoretical dark energy that affects the universe's accelerating expansion. Nevertheless, the data from the survey contains 20% of all currently-known TNOs, the researchers wrote, covering an eighth of the sky.

"These will be valuable for further detailed statistical tests of formation models for the trans-Neptunian region," they wrote.

Originally published on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.