11-Million-Year-Old Weird Worm Lizard Discovered

They look like snakes, but don't be fooled: Legless, slithering amphisbaenians are more closely related to lizards than to boa constrictors.

Now, the first complete skull of the ancestor of today's bizarre "worm lizards" reveals that these strange reptiles have been largely unchanged for at least 11 million years. The fossil skull, discovered in Spain, is only 0.44 inches (11.2 millimeters long), but represents a new species, Blanus mendezi.

This family, known as blanids, includes the only worm lizards found on land in Europe, said study researcher Arnau Bolet, a doctoral student at the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont in Barcelona.

"Their fossil record was until now limited to isolated and usually fragmented bones," Bolet told Live Science in an email. "Thus, the study of a complete fossil skull more than 11 million years old was an unprecedented opportunity." [The 12 Weirdest Animal Discoveries]

Lizards without legs

Worm lizards are found around the world today, though most of the 180 or so extant species live in the Arabian Peninsula, Africa and South America. Some have rudimentary legs, but most have no limbs at all, and resemble large earthworms.

Today, there are three groups of worm lizards in the Mediterranean region: one group is eastern, one is Iberian and one is northwest African. The Iberian and northwest African groups probably arose from one western Mediterranean group that only later subdivided, Bolet and his colleagues explain today (June 4) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

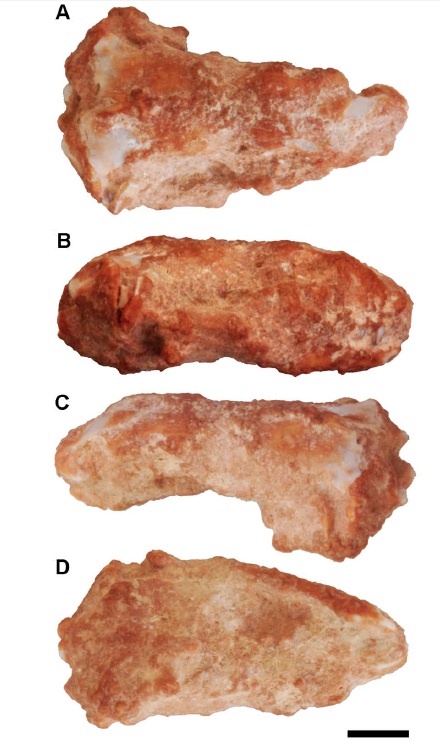

The new skull was found in sediments excavated in 2011 in the Vallès-Penedès Basin in Spain's Catalonia region. Manel Méndez, a technician at the Institut Català de Paleontologia Miquel Crusafont, was sifting through the dirt for fossils using a screen when he found a lumpy, pinkish rock that he knew was something more.

"We were lucky to have him doing this work, because it would have been relatively easy to dismiss the fossil," Bolet said. The skull is surrounded by a concretion of carbonate rock that has hardened around it like cement.

Locked in stone

Fortunately, Bolet said, Méndez "immediately realized that what he had found was a small vertebrate skull, a rather exceptional finding, because screen-washing techniques mostly retrieve disarticulated bones and isolated teeth."

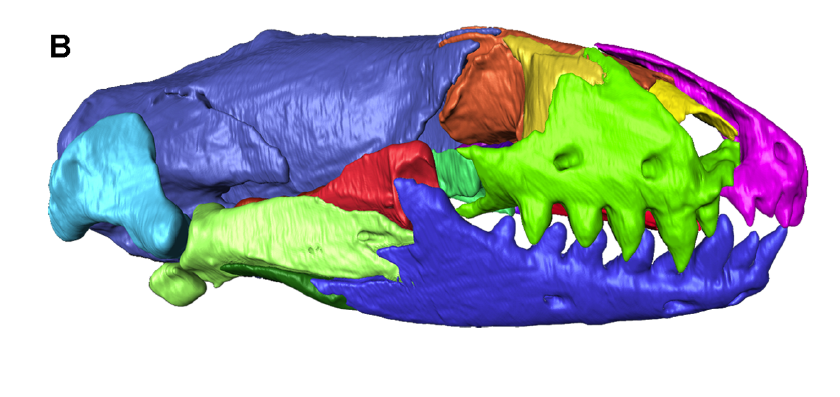

The researchers were used to working with tiny fossils, even ones less than a half-inch across, like this one. But removing the rock crust from the fossilized bone would be impossible without damaging the skull inside, they knew. So they turned to technology. Using computed tomography (CT) scanning, the same sort of imaging used in hospitals, the researchers created a virtual reconstruction of the bone still locked in the rock.

The result, Bolet said, is a three-dimensional digital model that allows the researchers to study the skull. They realized the specimen, which measured only 0.23 inches (5.8 mm) at its widest spot and had 20 teeth, was a previously unknown species. They dubbed the animal Blanus mendezi in honor of the technician who discovered the skull.

B. mendezi dates back to the Miocene epoch and is about 11.6 million years old, but its skull looked very similar to those of worm lizards alive today. The researchers suspect this species lived after the evolutionary split between eastern and western Mediterranean worm lizards, and represents the oldest known record of the western group.

The study also highlighted the mystery of worm lizards, Bolet said — even modern species.

"One of the things that became evident during this study was that the osteology of even living species of Blanus is still not well-known," he said. "At the same time, this precludes a proper identification of fossil specimens at the species level, because variation within species has been barely studied."

Ongoing research will need to focus on describing the bones of both fossil and modern blanids, Bolet said, in order to build a family tree for these wiggling enigmas.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.