Explainer: What is Vitiligo?

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Vitiligo, a human skin condition that turns patches of skin and hair white, it is not a disease we hear much about, although it affects approximately 1% of the population.

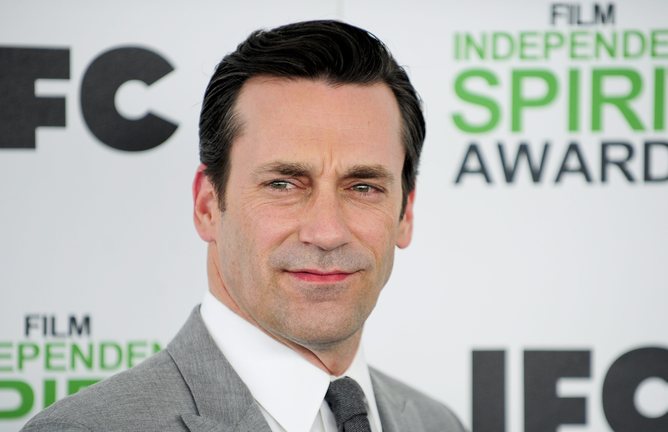

Most famously, Michael Jackson was diagnosed with the condition, but more recently Jon Hamm from TV’s Mad Men has it, as does model Chantelle Brown-Young on America’s Next Top Model.

So what causes these white spots, and how are they treated?

Vitiligo is thought to be an autoimmune condition that affects males and females of all ages and races. Immune system cells usually fight infection but in vitiligo, a person’s own immune system cells start to attack the skin’s pigment cells (melanocytes).

The destruction of the pigment cells result in white spots on the skin and sometimes also the mucosa (lips and genitals) and hair, eyelashes or eyebrows. This is not because the immune system is inactive or underactive but rather a result of it simply “behaving badly".

It is not an infection, nor is it contagious, cancerous or caused by food. It is generally not passed down to children and individuals that are affected are usually otherwise fit and healthy.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Some people may develop vitiligo in areas of skin trauma (such as surgery, cuts or abrasions) and some describe a worsening of the condition at times of stress but neither trauma nor stress cause vitiligo to develop.

People with vitiligo may have many white spots over different parts of the body or just one area of skin. White hairs (poliosis) and white skin around moles (halo neavus) may also be seen.

Unfortunately, there is no way to determine if a person’s vitiligo will be progressive over time. The condition undoubtedly carries a significant psychological burden for many which may impact on work, life and relationships. Education and increasing public awareness of vitiligo is the sure way to remedy this problem.

Vitiligo is best diagnosed by a dermatologist (medical doctor who specialises in conditions affecting the skin, hair and nails). Usually assessing the skin in the consulting rooms is all that is required but occasionally a skin biopsy (piece of skin) may need to be looked at under a microscope to clinch the diagnosis.

While there is no blood test to diagnose vitiligo, blood tests may be ordered to assess for other autoimmune conditions if deemed necessary.

Treatments in the spotlight

While not all patients with vitiligo will want to or need to treat their spots, others do – and for this group, treatments are available to try to regain pigment in affected areas.

Medicated creams and specialised medical light and laser sources are often the first step in treatment with most responding to this treatment. Results are usually seen within six months and treatment may be continued for up to two years if progressing well.

Hair-bearing areas such as the arms, legs and face respond better than non-hair bearing areas such as the hands, feet and lips to this treatment.

In special situations, surgical techniques (such as punch grafting, blister grafting and non-cultured melanocyte transfer) may be used to try to regain pigmentation. For those who wish only to conceal affected areas, cosmetic camouflage agents are available, each with their own advantages and disadvantages.

There is also a medicated bleaching cream available for those with very large areas of involvement on the body who prefer to “go white” and remove colour from the few remaining patches of normal skin.

A holistic approach to care is essential with counselling being a very valuable part of some peoples’ treatment plan. The exact treatment regimen chosen must be carefully and individually tailored by a dermatologist.

Exciting developments are being made in the area of vitiligo therapeutics with new treatments on the horizon including immune modulators (called “biologics”) and those resembling melanocyte-stimulating hormone.

Vitiligo has, for too long, been a condition shrouded in mystery. The time has come to reveal the truth, educate the community and raise awareness of this condition.

June 25 is World Vitiligo Day – visit the Vitiligo Association of Australia website for more information.

Michelle Rodrigues does not work for, consult to, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has no relevant affiliations.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.