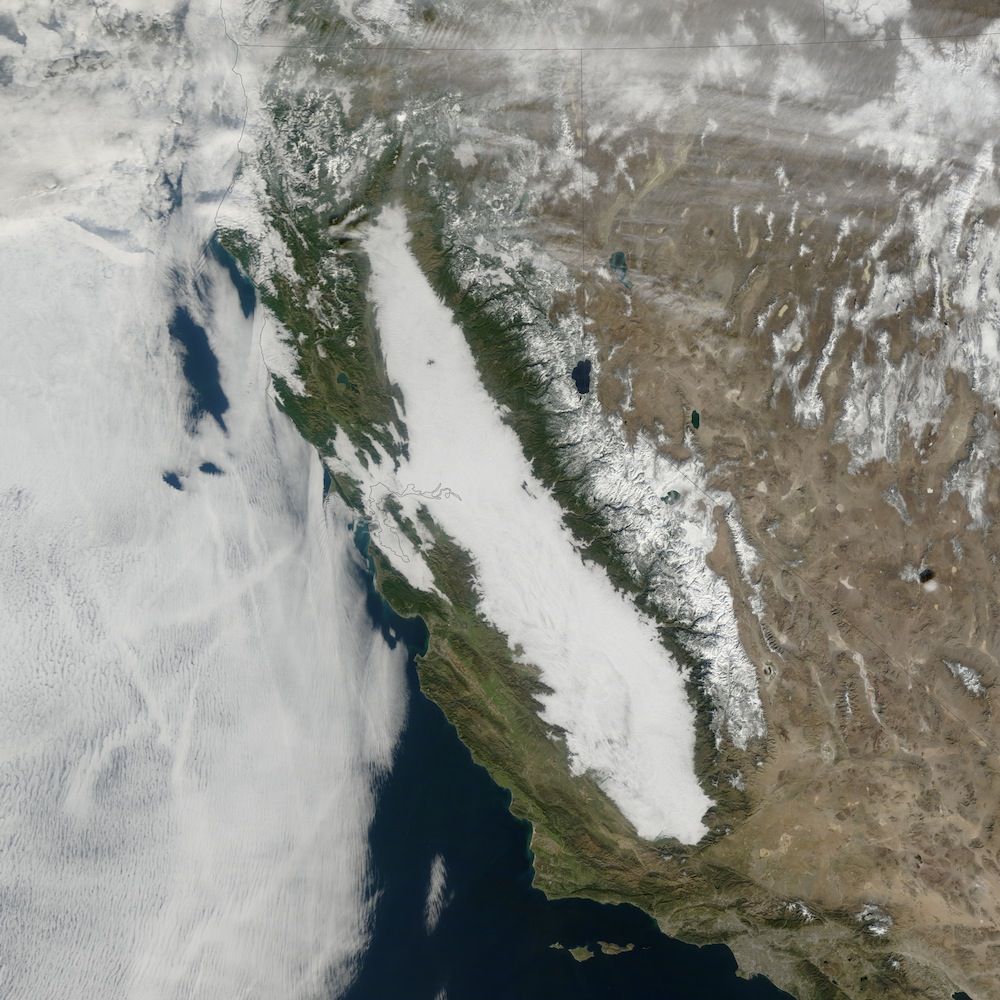

California Tule Fog Becoming Increasingly Rare (Photo)

At first glance, this image might seem to show Central California covered in snow. But that white stuff isn't the makings of a winter wonderland. It's thick, dense fog known as tule fog.

Tule fog season in California is traditionally between November and March, when rains bring moisture to the state's Central Valley. The term "tule" comes from the plant of the same name (Schoenoplectus acutus), which dominates marshes in the region.

But tule fog may not be the defining feature of Central Valley winters for much longer. A new study, published May 16 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, found that the number of winter fog events declined by 46 percent over the past 32 winters. [Fish Rain & Fire Whirlwinds: The World's Weirdest Weather]

Vanishing fog

The conditions varied year by year depending on the level of moisture, study leader Dennis Baldocchi, a biometeorologist at the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement.

"Generally, when conditions are too dry or too wet, we get less fog," Baldocchi said. "If we're in a drought, there isn't enough moisture to condense in the air. During wet years, we need the rain to stop so that the fog can form."

This image of tule fog was taken Jan. 17, 2011, by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer on NASA's Terra satellite, according to NASA's Earth Observatory, which released the image on June 5.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fog and fruit

The decline of tule fog has pros and cons. Dense fog frequently causes traffic accidents in the Central Valley, some on a very large scale. In 2007, for example, dense fog on California's Highway 99 near Fresno caused an 108-car pileup that killed two people. Fewer days of fog means less risk of deadly accidents.

But tule fog is also crucial to the Central Valley's fruit and nut crop, which represent about 95 percent of U.S. production of foods such as cherries, almonds, peaches and apricots, according to UC Berkeley. Fruit and nut trees need a winter chill period to become dormant, and tule fog helps contribute to that chill.

As fogs decline, so have winter chills, Baldocchi and his colleagues reported. The number of winter days with temperatures between 32 degrees and 45 degrees Fahrenheit (0 degrees to 7 degrees Celsius) in the Central Valley have dropped by several hundred in the past 60 years.

For fruit trees, the fog and temperatures are related, Baldocchi said. A shroud of fog shields the trees from sunlight, keeping their buds cooler. As a result, farmers may need to cultivate more heat-hardy trees, or move orchards to cooler spots.

California's current drought is unlikely to help matters, as it is starving the state of the moisture needed to form tule fog. California's final full snowpack survey of the winter, on May 1, found that the moisture stored in the state's snow is at 18 percent of normal. A more limited, automated survey conducted on May 30 suggests that snowpack was at only 3 percent of normal on that date.

As of May 30, most of California's major reservoirs were at 50 percent capacity or lower, according to the state's weekly drought report. There have been 1,852 wildfires in the state since Jan. 1, exceeding the year-to-date average of 1,074.

Editor's Note: If you have an amazing weather or general science photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Jeanna Bryner at LSphotos@livescience.com.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.