Human Behavior, Not Hurricane Names, Dictates Danger (Op-Ed)

Joshua Klapow is an associate professor of public health at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He is also the chief science officer for ChipRewards Inc., a population health technology company. He contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights

The recent study examining the difference in fatality rates among female- versus male-named hurricanes is a fascinating one.

As a behavioral scientist and chief science officer of a population-based organization, I was immediately drawn to both the creativity and the implications of the study. It is not commonplace to see the use of large archival databases combined with small yet highly controlled experimental studies designed to tease out gaps in the large data. This is a great example of how big data and "little data" can work together. [Gender Bias May Make Female Hurricanes Deadlier]

The study by Kiju Jung and colleagues at the University of Illinois should be valued for its scientific creativity. It should not, however, be valued for its immediate real-world implications. The concept of a name having so much impact as to affect fatality rates is fascinating and concerning. It is so easy to immediately jump from the findings to the implications — and that can be a deadly flaw.

Science and the concept of scientific study are critical for humanity's understanding and development of knowledge. However, we have to take science for what it is. It is observations and quantification of those observations.

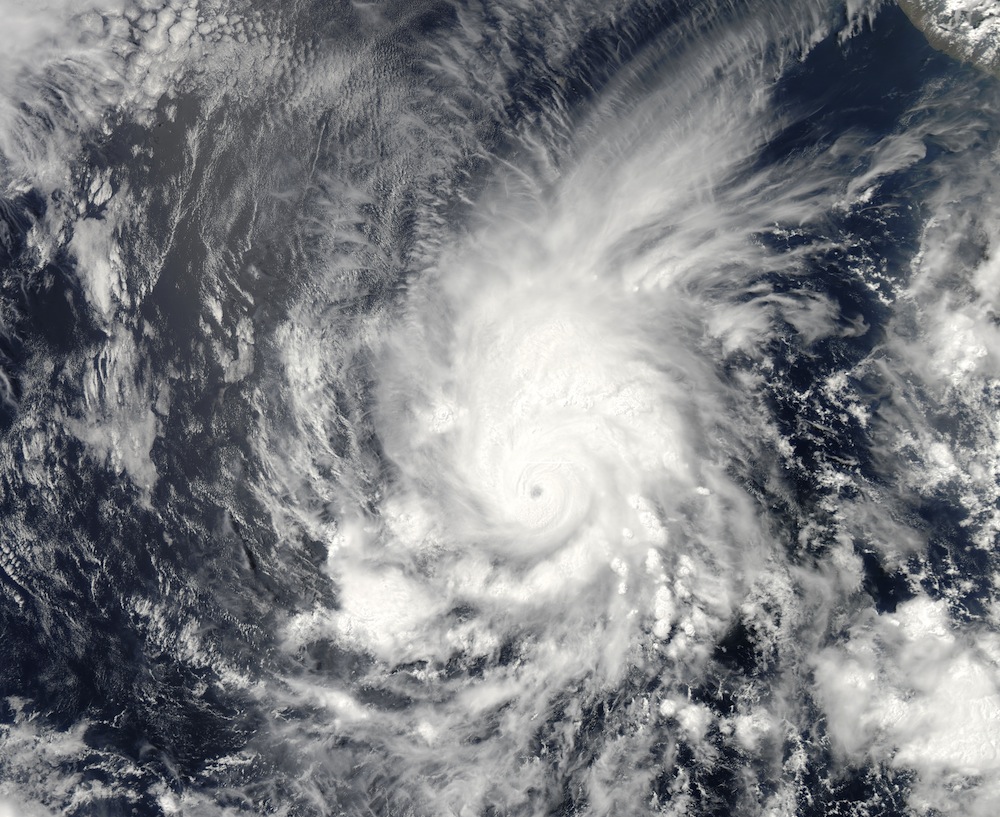

Every year thousands of people die in natural disasters. The field of disaster preparedness constantly struggles with getting individuals to engage in appropriate health behaviors that will keep them safe. From emergency plans and preparedness kits, to complying with evacuation instructions, we sadly see that a lack of preparation and behavioral action often results in fatalities.

The true, real-world implication of this study is that people place different meanings on names. The archival data are interesting and a starting point, but like other big-data analytics, they have significant limitations. The fact that there are any differences in fatality rates, and the fact that there are any differences in the way people perceive names, tell us that there are psychological factors associated with natural disasters. Did we already know that? Common sense would say, "Of course."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But common sense is not solidified until there is documentation. Science can do that for us. It can take our common sense hypotheses and turn them into reliable and stable observations.

People typically think about preparedness as a functional exercise, one that involves logistics and operations. What the Illinois study shows is that preparedness is also very much about human behavior. Moreover, it reminds us that human behavior is influenced not just by outside or environmental factors, but by internal psychological factors as well.

It is easy to infer from the study that there is something magical in a name. I would argue that it's easier to infer from this study that human behavior is influenced by everything from the external environment to the internal meaning of the label or symbol.

Should we conclude that female hurricanes are deadlier? Even if we do, should it impact our approach to disaster preparedness?

This study is an interesting demonstration of science. However it is not a call for changing the names of hurricanes. Rather it's a powerful reminder that humans are very much influenced by a multitude of factors. Deadly hurricanes, male or female, are just that: deadly. [In Photos: Notorious Retired Hurricane Names ]

If we rename every hurricane with the male name would we save lives? Possibly. But let us not be fooled that that is the answer. The answer lies in the complexities that make-up human behavior.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.