Ant Sperm Bundle Up to Outrace the Competition

The race to fertilization is no every-sperm-for-itself sprint in desert ants. A new study finds that bundles of these ants' sperm work together to swim faster than any single sperm could.

The sperm of the ant Cataglyphis savignyi are some of the few sperm cells ever found to cooperate. The stakes are high: Females of this species mate with many males in quick succession, and only the quickest, strongest sperm end up stored in the female sperm storage organ, the spermatheca. There, sperm can live for 20 to 30 years — far longer than the males that produced them, which survive mere weeks.

"In the end, the higher the proportion of your own sperm stored in the spermatheca, the more offspring you will have," said study leader Morgan Pearcy, who researches evolutionary biology and ecology at the Université Libre de Bruxelles. [Sexy Swimmers: 7 Surprising Facts About Sperm]

Sperm synergy

Pearcy and his colleagues discovered the speedy sperm bundles by accident. The researchers were studying sperm competition in female ants, some of which mate with only one male and some of which mate with many.

To investigate the phenomenon, the team chose the ant with the highest number of matings, C. savignyi. The queens of this species — brownish-red, unassuming desert ants — mate with an average of nine (and up to 14) males one after another. They then store the males' sperm in the spermatheca, keeping it there for life. And queens can live to a ripe old age — at least 20 years in laboratory conditions, Pearcy said. It's unclear how long they live in the wild, but they likely survive at least a decade, he said, because it takes many years for a queen to establish a new, self-sustaining colony.

Reproductive race

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In contrast, males of the species live a few weeks, at best. Pearcy and his colleagues captured ants from the Arad desert in Israel and raised males to maturity. At 28 days, they killed the ants with chloroform. In death, the ants' penis structures (called the endophallus) popped out of the abdomen. The researchers squeezed the ants' abdomens and collected the semen that oozed out of each endophallus.

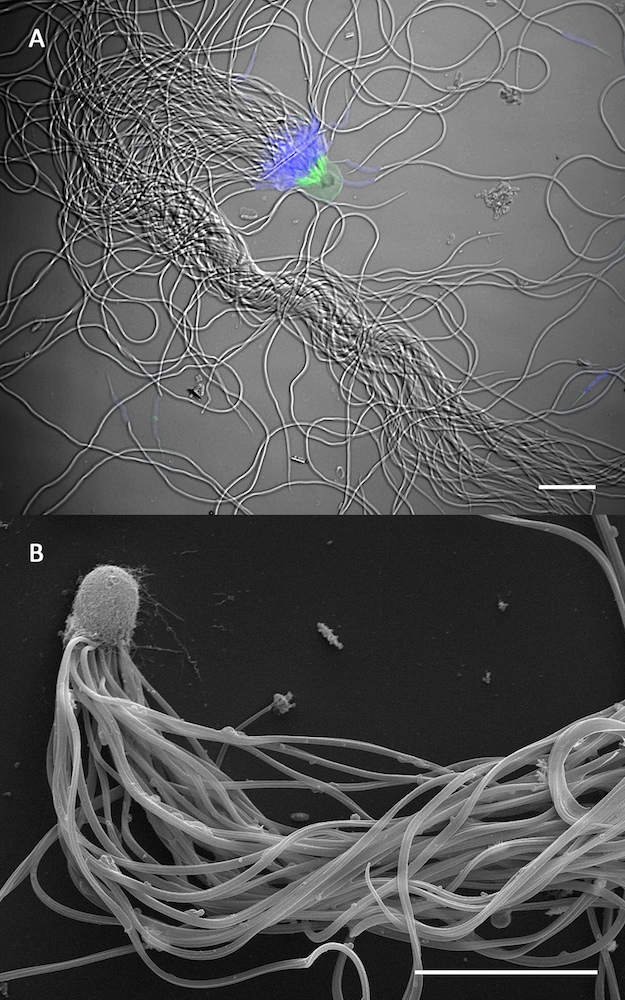

Under the microscope, the researchers could see that most of the sperm was bundled by the dozens, with an average of 73 sperm per bundle. They then introduced the ant sperm to fluids of varying viscosity, ranging from very fluid to more slow and sticky than syrup. Under a microscope, they set the sperm racing against one another, measuring, in particular, how quickly bundled sperm moved compared with single sperm.

On average, the bundled sperm swam twice as fast as their single counterparts, the researchers found. When comparing an ant's bundled sperm with its own single sperm, the teamwork advantage still persisted: Bundled sperm swam 50 percent faster than singletons from the same individual.

To swim, the bundled sperm move their flagella in a coordinated spiral motion, corkscrewing their way through the fluid. The scientists didn't find any bundles in the spermatheca of ant queens, suggesting the sperm disband when they reach their destination.

Competition and cooperation

The speed of the bundled sperm likely helps them beat out other sperm in the competition for space in the spermatheca, Pearcy said. These sperm may also be more energy-efficient swimmers, which could help save resources for their long wait inside the spermatheca. Bundles could also be better at elbowing other sperm out of the spermatheca, though there is no evidence that they play bouncer so far, Pearcy said.

Few other examples of sperm cooperation exist in the wild, Pearcy said. The sperm of the opossum Monodelphis domestica appear to work in pairs, while the sperm of the wood mouse Apodemus sylvaticus join in long trains that swim faster than individual sperm. The sperm of some diving beetles link up in chains of hundreds or thousands, perhaps to navigate the females' complicated reproductive tracts.

Editor's Note: If you have an amazing or general science photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Jeanna Bryner at LSphotos@livescience.com.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.