Great White Sharks Are Making a Comeback off US Coasts

Good news for great white sharks: The species' numbers are on the rise off both the east and west coasts of the United States, two new studies show.

The species had been feared to be in decline, but the research suggests conservation efforts have given great whites a boost.

"It's a good news story and one we don't hear often enough with sharks," said George Burgess, a researcher at the Florida Museum of Natural History at the University of Florida in Gainesville. [Image Gallery: Great White Sharks]

Great mysteries

Despite their name recognition, the sharks made infamous by the movie "Jaws" are rather mysterious in the wild, and it's difficult for scientists to get a handle on their population size.

Great whites are generally solitary creatures that spread out widely. Populations typically don't aggregate around regular feeding areas, especially along the East Coast. With adults sometimes growing to be more than 20 feet (6 meters) long, great white sharks are not easy to capture, and unlike whales and other marine mammals, sharks don't need to go to the surface to breathe.

"They're rare animals," said Tobey Curtis, a shark researcher at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Greater Atlantic Regional Fisheries Office in Gloucester, Massachusetts, who led one study on great whites off the East Coast, published in the journal PLOS ONE this month. "They're not commonly seen, and it takes a lot of effort to track down verified records of sightings and fishery captures."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A rise in the East

Curtis and his colleagues compiled 649 confirmed records of western Atlantic great white sharks from the years 1800 to 2010, through sources as varied as commercial catch data, fishing tournament results and newspaper articles. The group said their records make up the largest dataset of great white sharks ever collected for the region.

The team didn't have enough information to estimate a real number for the area's shark population, but they were able to establish a relative trend. Their analysis suggests the great white shark population took a dive in the 1970s and 1980s with the expansion of recreational and commercial shark fishing. But sightings of the species started to rise again after conservation and management efforts took effect in the 1990s.

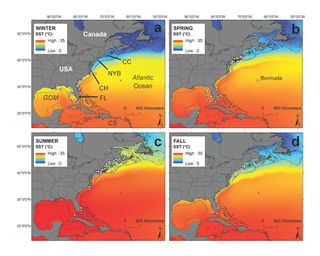

The study also identified patterns showing where the sharks tend to move throughout the seasons: They like Florida waters in the winter and move northward in the spring, sometimes traveling to places as far as Newfoundland and the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Canada.

California comeback

Burgess, who was involved in Curtis' study, separately led another investigation published in PLOS ONE this month to estimate great white shark populations off the coast of California. Unlike their counterparts on the East Coast, West Coast great whites tend to gather around feeding hotspots where seals and sea lions congregate. (Right now, on the East Coast, the only place to reliably spot the sharks is off Cape Cod, thanks to a gray seal comeback over the last several years, which has attracted great whites to the region.)

Burgess said he found that earlier reports about the demise of great white sharks had been overstated. His data suggested that California populations are on the rise — perhaps 2,000 individuals strong. In contrast, an earlier study from researchers at Stanford University suggested that just 219 great white sharks lived in the region.

The researchers can only cautiously declare victory for conservation efforts. Sharks and other elasmobranchs — a group that includes rays and skates — all share biological traits that make it difficult for their populations to recover from sharp declines. They grow slowly, reaching maturity at a late age, and because females are fertilized internally, they can only have a limited number of offspring at a time.

And without much historical data, scientists also have difficultly establishing a baseline against which to measure their conservation success.

"They're back on the way up, but to be honest, I don't think any of us know what 'up' is," Burgess told Live Science. "The fact is, we have no real idea what [the population] was before we started screwing around with the environment on both coasts."

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Most Popular