Worst Spots for Weather Extremes Found

Frightful floods, freezes and heat waves favor certain parts of the Northern Hemisphere, the result of strong atmospheric currents that steer extreme weather to the same places over and over again, a new study finds.

Fear a cold winter? Then avoid eastern North America. Hate floods? Stay out of western Asia. Enjoy a long shower? Then drought-prone central North America, Europe and central Asia aren't for you. Can't stand the heat? Rule out heat-wave-prone western North America and central Asia, according to findings published today (June 22) in the journal Nature Climate Change.

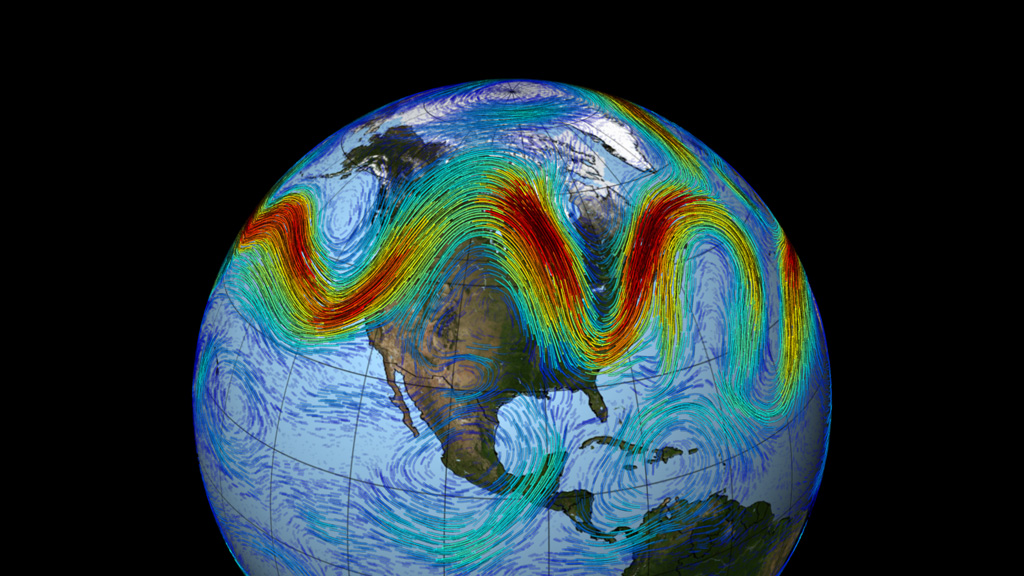

The atmospheric currents that control the bad weather are similar to a sky river: They swoop back and forth across the hemisphere at about 3 miles (5 kilometers) above the surface, with giant waves that resemble the Mississippi River's wide bends. The currents also have vertical pressure waves that vary like a riverbed that shallows and deepens — these contribute to the pressure highs and lows in daily weather reports. [Infographic: Tour Earth's Atmosphere Top to Bottom]

These atmospheric waves shove air around the planet, sucking warmth up from the tropics and cold air down from the Arctic. Extreme weather hits when the swoops freeze in their tracks, trapping storms, heat or cold in place for weeks.

"We're not saying these extremes are becoming more prevalent," said lead study author James Screen of the University of Exeter in the U.K. "These waves have preferred locations, so you're more likely to get extreme weather in one place over another."

However, many weather observers have noted an apparent rise in extreme weather in recent decades. This has led some researchers to blame global warming for altering these wind patterns, resulting in more stuck air waves and more frightful weather.

The new research did not examine the link between global warming and extreme weather, however. Rather, scientists set out to test one of the idea's main tenets: that these planetary air currents really cause terrible weather.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The narrative I've been reading is almost like these waves can cause anything, anywhere, anytime, but it actually doesn't seem to be that way," Screen said.

Only month-long severe temperature and rainfall events, not a few days of miserable weather, merited a look in the study. The researchers examined these extreme weather events, along with past atmospheric wave patterns, from 1979 through 2012. (Screen said the 2013-2014 "polar vortex" winter in eastern North America would have qualified for the study.)

The scientists discovered the waves tend to get stuck in the same spots over and over again. These "preferred locations" are influenced by topographic features such as mountain ranges and oceans.

The currents studied by Screen and his co-authors are shallower than the more well-known jet stream, which flows at about 6 miles (10 km) above the ground. However, the shallow currents "play an important part in controlling our weather," Screen said.

Now that the team has identified which regions of the Northern Hemisphere are most strongly affected by stuck planetary waves, the next step is thinking about what might happen if the waves get larger, as some researchers predict might happen under the influence of global warming.

"The meteorological implication is that climate change is not necessarily going to make everything more extreme everywhere," Screen said.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.