Strange Stone Spheres Top List of New World Heritage Spots

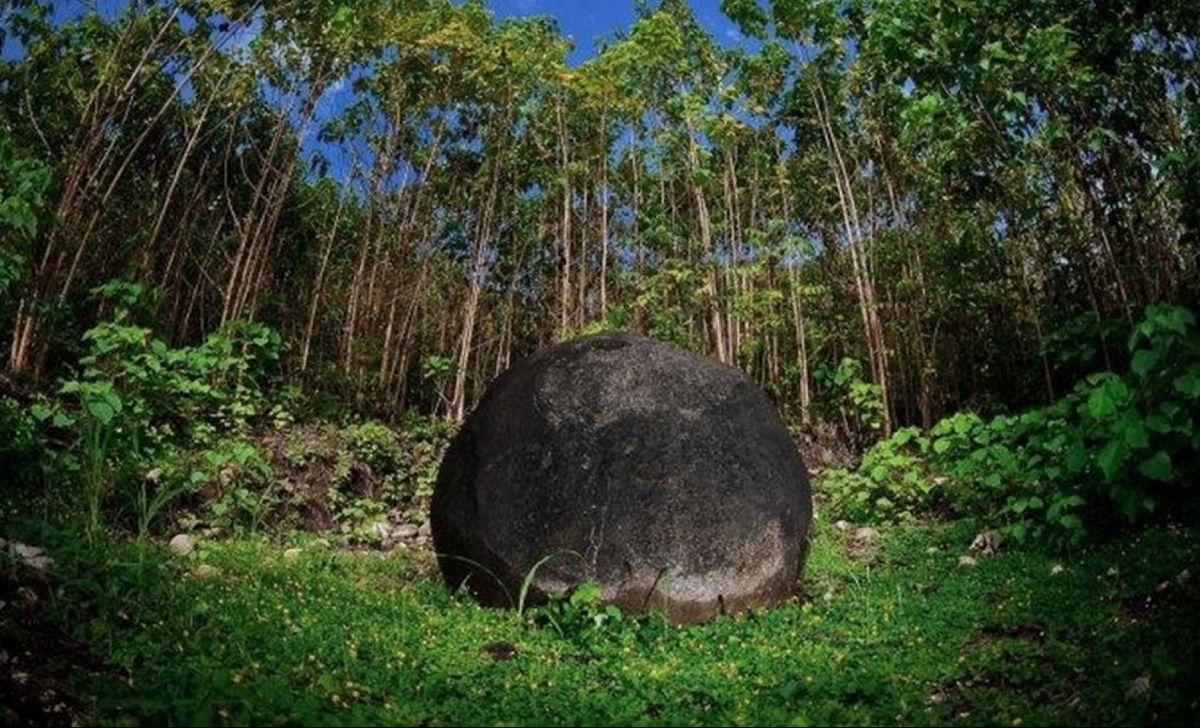

Enigmatic archaeological sites in Costa Rica dotted with mysterious stone spheres are among six new spots newly designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The stone sphere sites, on the Diquis Delta in southern Costa Rica, join places like the Great Wall of China and Yellowstone National Park on the list of 1,007 sites designated as World Heritage Sites by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). The organization lists places that are "of outstanding universal value," based on criteria such as representing a masterpiece of creative genius, recording testimony of a vanished civilization, or containing exceptional natural beauty.

The U.N.'s World Heritage Committee, currently meeting in Doha, Qatar, announced the additions to the list today (June 23). Other than the Diquis Delta sites, the new honorees include the architectural remnants of a medieval Eurasian city, spectacular landscapes in Vietnam and India, a wildlife sanctuary in the Philippines and a site offering geological evidence of the meteorite collision that killed off the dinosaurs. [See Photos of the New World Heritage Sites]

The new sites are:

1. Bolgar Historical and Archaeological Complex, the Russian Federation: Along the banks of the Volga River, south of Kazan, Tatarstan, is an archaeological site containing the remnants of the medieval city of Bolgar. Built in the seventh century by a civilization called the Volga-Bolgars, Bolgar remained an important town until the 15th century, according to UNESCO. In the 1200s, it was the capital of the Golden Horde, the northwestern region of the Mongol Empire. The Volga-Bolgars converted to Islam in A.D. 922, and the site remains a destination for pilgrimages by Tatar Muslims today.

2. Pre-Colombian Chiefdom Settlements with Stone Spheres of the Diquis, Costa Rica: Consisting of four archaeological sites in the Diquis Delta, this new site encompasses the archaeological remains of human civilization before Europeans arrived in Costa Rica. The sites date to between A.D. 500 and 1500 and include burial sites, paved areas and mounds, according to UNESCO. Most intriguing, however, are the stone spheres that dot the sites. These spheres range in size from 2.3 feet to 8.4 feet (0.7 to 2.57 meters) in diameter, and many remain in the locations where they were placed centuries ago. No one knows how the stones were made — or why. [The 7 Most Mysterious Archaeological Finds on Earth]

3. Trang An Scenic Landscape Complex, Vietnam: The stunning landscape on the south side of the Red River delta in Vietnam earned this area a place on the UNESCO list. Dramatic limestone peaks and mountainside caves define this region of so-called karst topography. (Karst landscapes are formed when easily dissolvable rocks such as limestone erode into impressive shapes, typically pockmarked with caves.) The caves contain artifacts of human settlement dating back 30,000 years. Today, the site also includes Hoa Lu, the capital of Vietnam in the 10th and 11th centuries, as well as villages, temples and farms.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

4. Great Himalayan National Park, India: This national park in the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh is rich in both beauty and biodiversity. Located in the western Himalayan Mountains, the park's landscapes include low, wet plains, high, dry deserts, mountain peaks and major rivers. Threatened species, including the endangered snow leopard and red-headed vulture, call this park home. This site is extremely important for biodiversity conservation, according to UNESCO.

5. Mount Hamiguitan Range Wildlife Sanctuary, Philippines: The iconic Philippine eagle and the striking white-and-red Philippine cockatoo make their homes in this species-rich sanctuary, which runs north-south along the Pujada Peninsula of the Philippines. At least 11 endangered vertebrates live in the range, along with dozens of species that can be found nowhere else on Earth.

6. Stevns Klint, Denmark: The striking white chalk cliffs on Denmark's island of Zealand aren't just beautiful. They're paleontological wonders. These cliffs are made of rocks set down at the end of the Cretaceous and the beginning of the Tertiary 65 million years ago. A layer of ash likely marks the spot in time when a meteorite crashed half a world away in Mexico, filling the atmosphere with sun-obscuring dust and probably killing off the dinosaurs. This 9-mile-long (15 km) stretch of cliffs is the longest, best-exposed geological site showing this boundary between eras, according to UNESCO.

In addition to the six new sites, UNESCO expanded three existing World Heritage sites. These expanded regions include the South China Karst site, which will now be 124 acres (50,000 hectares) larger. This site, on the list since 2007, encompasses a stunning karst landscape in four provinces in southern China.

The second extension was granted to the Białowieża Forest on the border of Belarus and Poland, which has been a World Heritage Site since 1979. Here, primary forest provides shelter for the European bison, which was once hunted to extinction in the wild. Now reintroduced, the bison is Europe's largest land animal.

Finally, UNESCO extended the Dutch and German Wadden Sea World Heritage Site, which has been on the list since 2009. This expanse of wetlands and mud flats sits in the southeastern North Sea and is home to hundreds of thousands of birds, as well as seals and other species.

Editor's Note: If you have an amazing World Heritage Site photo you'd like to share for a possible story or image gallery, please contact managing editor Jeanna Bryner at LSphotos@livescience.com.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitterand Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.