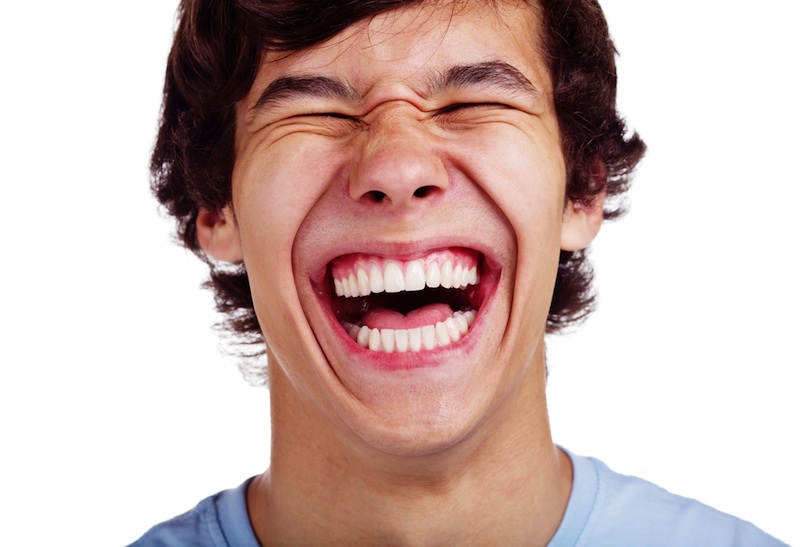

SAN FRANCISCO — Ask a woman from a remote village in Bhutan to act as if she's embarrassed, amused or awed, and chances are, a teenage boy in the United States could guess exactly what emotion she was portraying.

Human beings have dozens of universal expressions for emotions, and they deploy those expressions in recognizable ways across several cultures, new research finds.

That number is far greater than the range of emotion previously thought to be the similar around the world. [Top 10 Things That Make Humans Special]

Common core

For decades, scientists have held that there are six basic human emotional expressions, all revealed in the face — happiness, sadness, disgust, fear, anger and surprise.

But about five years ago, Daniel Cordaro, a psychologist at the University of California at Berkeley and Yale University, began wondering if there were more. He spent hours watching people in cafes or downloading YouTube videos of children across the world unwrapping birthday presents with big smiles on their faces. He noticed that despite cultural differences, many more-complicated expressions seemed similar across cultures.

To test the idea, Cordaro and his colleagues showed people from four continents a one-line description of a story (which the researchers translated into the various native languages), such as "Your friend just told you a very funny story, and you feel amused by it," or "Your friends caught you singing along loudly to your favorite song, and you feel embarrassed," then asked the participants to act out this emotional state using no words.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the researchers shared those emotional reenactments with people from foreign cultures, the viewers could match 30 facial and vocal expressions to the associated stories with better accuracy than if they had simply guessed. (Interestingly, expressions of sympathy, desire and coyness didn't seem to translate across cultures.)

The team also compared people in China, Japan, Korea, India and the United States when reenacting these emotions, then coded 5,942 of their facial expressions. This meant meticulously recording the positions of 25,000 different facial muscles, Cordaro said.

"We found these incredible patterns: There are lots of similarities in how people are producing these expressions," Cordardo said. "I started to feel for the first time how similar I was to everyone around me."

(Some expression were incredibly similar across cultures, whereas others, such as the sound "aww" to react to something cute, were not universal.)

Distant but similar

But most of the people initially studied in this research belonged to cultures largely linked by TV, smartphones and other technology, meaning the emotional expressions examined may not be truly universal.

So Cordaro and his colleagues trekked to a remote village in Bhutan that outsiders had never visited. The researchers asked the villagers to pair vocal tracks with a story that was being described. For 15 out of the 17 vocal expressions, the villagers could pick the corresponding situation at rates that were better than chance.

The findings suggest that a vast part of the human emotional repertoire is universal, and that emotional expressions go far deeper than the six basic ones previously described by researchers.

But the findings shouldn't underplay the role of culture, Cordaro said.

"Each emotion boils down to a story," Cordaro said. "Culture teaches us the stories under which we use these emotions, but look underneath them, there will be some theme."

Personal epiphany

While translating basic emotional concepts for Bhutanese villagers, the researchers also came upon a Bhutanese word that had no English equivalent: "chogshay," which loosely translates to a fundamental contentment that is independent of a person's current emotional state.

For instance, someone could be in the throws of rage or feel horrendously ill, but their underlying sense of well-being could still be intact.

"Fundamental contentment is a feeling of indestructible well-being resulting from unconditional acceptance of the present moment," Cordaro said.

At first, the notion of chogshay was completely alien to Cordaro, who was used to defining well-being in terms of what he had, how he was feeling and what he was striving for. But through a process of recognizing the universality of many human emotions, and after completing a round of Buddhist meditation in Thailand, Cordaro experienced the chogshay state.

"I felt complete blankness," Cordaro said. "It was the most beautiful moment in my entire life."

Different access points

This state of contentment may be available to people all the time, but different cultures may instead emphasize emotional states that could crowd out that awareness, Cordaro speculated.

He also hypothesizes that people can access this state in many different ways, whether by self-reflection, meditation or achieving "flow" in highly engaging activities.

Cordaro discussed his experiences on Tuesday (June 24) at a presentation organized by the Being Human foundation in San Francisco.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.