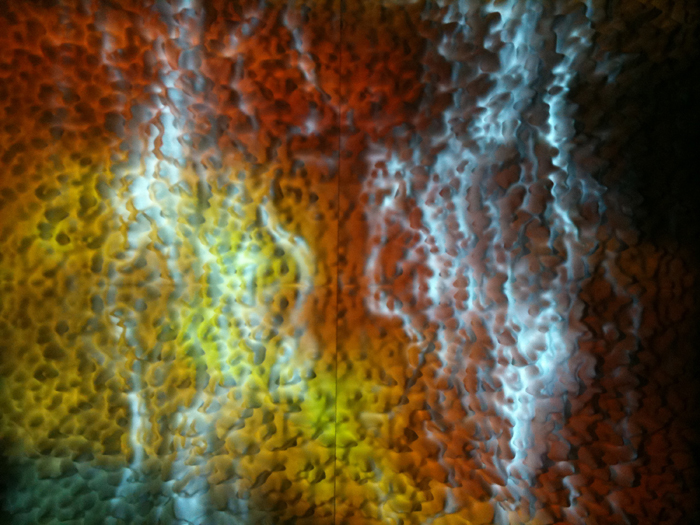

Science As Art: Soundscapes, Light Boxes and Microscopes (Op-Ed)

Dynamic Extensions III, digital photo, 2012, 22.5 inches by 61 inches. (Image credit: Patricia Olynyk)

Paulette Beete, NEA senior writer-editor, contributed this article as part of partnership between NEA and Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Can we really believe all that we see? How much does an experience depend on what we perceive with our eyes? How much depends on our other senses?

These questions lie at the heart of the work of visual artist Patricia Olynyk. Using tools of science — microscopy and biomedical imaging — Olynyk creates installations that explore how people's sensorial experiences of their physical environments impact their understanding of them. As she notes on her website, "I investigate the often-tenuous relationships between human culture, science, and the environment."

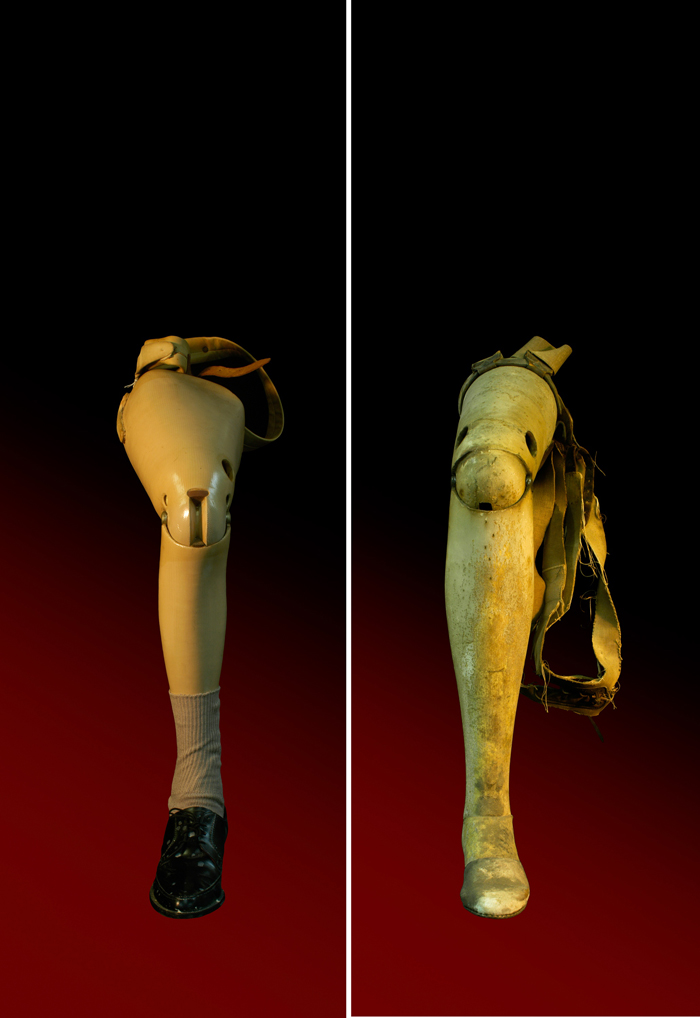

Dark Skies, for example, an installation including projections and a soundscape drawn from field recordings taken in the Rocky Mountains at twilight loosely explores the concept of biomimicry and the complex relationship between natural forms at the micro- and macro-levels. The Archive — a series of photographs and light box sculptures that recontextualizes historically valuable anatomical models, gynecological instruments and prosthetic devices — examines how humanity's relationship with the human body changes when we view it as an assemblage of parts rather than as a whole. As these projects illustrate, Olynyk's work shake's the viewer out of what could be called a complacency toward the world around us. [Art, As It Transforms the Environment ]

Olynyk has exhibited her work at the Brooklyn Museum, Museo del Corso (Rome), Saitama Modern Art Museum (Japan), and the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. She has also held multiple residencies at the College of Physicians in Philadelphia, Canada's Banff Center for the Arts and at the Pyramid Atlantic Center in Maryland.

She is former chair of the Leonardo Education and Art Forum, co-founder and co-organizer of Leonardo's NY LASER salons, and a professor of Art at Washington University in St. Louis, where she also directs the Graduate School of Art. We spoke with Olynyk about her work at the intersection of art and science and her investigations into how perception of the world impacts one's view of the world.

The power of the visual

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

OLYNYK: About ten years ago, a number of artists interested in the creative inquiry of scientific images were asking themselves, "What is the aesthetic of disease? Of the hepatitis C virus? What is the aesthetic of cancer? What is the aesthetic of the scientific or laboratory image?"

Peter Galison and Caroline Jones wrote a terrific book that addressed this and other subjects, "Picturing Science, Producing Art." It was a great book because the first chapter tackles a sticking-point question right away: What makes the science image, and what makes the art image?

Basically, Galison and Jones were saying what I've always believed intuitively to be true, and that is that both science and art images exist in the world. And so rather than sitting and pondering forever whether a visual is an art work or a scientific image, it's more productive to say a multitude of images exist in the world — and to ask what they do. Where do they live? What kinds of inquiries do they prompt? What do they beg of the viewer? So for me, it's the power of the visual that changed my work but also changed my worldview.

My window into science was always the power of the visual. My art practice has expanded beyond that to question even the power of the visual as primary by challenging ocular-centric tendencies. By that I mean that there is enthusiastic interest in scientific visualization and data capture amongst artists and scientists alike, particularly in recent years with the advent of new technologies that record our world at the macro, micro and nano scales. Some of these include MRI technologies, scanning electron and scanning tunnelling microscopy, and digital tomosynthesis. Also, elaborate and sometimes unconventional recording devices allow for the sonification of the living world (the transformation of data into acoustic signals). Such translations allow artists to move beyond the visual into other sensory experiences and to engage the discourses of cognitive science, aesthetics, psychology, and human consciousness in expanded ways through the reinterpretation of our environment.

This is probably one of the reasons why I've moved into producing installation works that provide a kind of embodied or spatialized experience for the viewer, and why I'm collaborating so much with sound designers and architects, at this point. But the power of the visual is evident when you look at microscopic images, and there's such a strong aesthetic even if the thing you're looking at is something that one would consider to be evil or bad, such as the case with images of disease. Though I don't use such images myself, they can certainly be viewed through the lens of contemporary aesthetics.

Early engagement with the arts

I had parents who were deeply supportive of whatever sort of proclivities I tended to show as a child. So from very early on, I was drawing. And I can remember one of my earliest art-related memories being with my mother, and I was four years old and she had these large pads of paper. They were almost poster-sized and they had numbers printed on them, and one was meant to use those numbers as a shape to press out some kind of drawing from the imagination.

And so my mother and I used to sit for hours and turn those numbers into faces and a variety of creatures.

If I was being punished, those papers were taken away from me, but then I would turn to my own body to draw. So I covered myself with drawings scribbled in blue BIC pen. I was almost tattooing myself so it was quite humorous.

I was an avid and determined drawer. And I was never dissuaded by my parents, ever, from pursuing some kind of career in the arts. I'm one of the fortunate few, I guess.

Inspiring wonder in kids

I had parents, especially a father, who really wanted to provide experiences that would inspire wonder. So from a young age, I had that advantage in combination with private art lessons.

Whereas most young students where I grew up were getting art lessons at school, I was fortunate enough to have private lessons with someone who was actually a career painter in Calgary — and who spent a lot of time with First Nations people in Western Canada.

I had the private lessons between the ages of nine and seventeen, and then went through the regular school circuit: Undergraduate degree at the Alberta College of Art and Design in Canada and a Masters in Fine Arts (MFA) from the California College of the Arts. I got my MFA with distinction there. And then I got two back-to-back scholarships to be a visiting scholar in Japan for four years. So I was educated in three countries. It gave me a broad worldview on contemporary creative practices.

And then I came back to the Bay Area and was the production manager for Suzanne Lacy’s Roof is on Fire project, which was a multi-layered feminist and inner-city youth art project and performance piece involving over 200 high school students from the Oakland Unified School District. Three years of media literacy training culminated in a three-hour long "performance" on the rooftop of a parking garage in Oakland where audience members simply engaged in empathic listening as teens debated various issues pertinent to their lives (which brings us back to the power of the auditory experience). Through a series of unscripted conversations, the youth participants addressed a variety of topics that included sex, AIDS, drugs, race, gender, music, media and teen rites of passage.

I then became interested in a number of local observatories, such as the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, which was associated with UC Berkeley. I had some interest in science, but I didn't really have access to labs or to teaching art and science until I got a full-time position at the University of Michigan in 1999. I was there for eight years and I had a lot of contact with scientists in my first tenure-track teaching position. I was also offered a courtesy appointment at the university’s Life Sciences Institute, directed by Alan Saltiel, which was an inspiring and transformative experience.

Science and art

Some people think that my love of science was an outgrowth from my father, who was one of several engineers in my family. But I have to say I think it was my fascination with the intersection of life at micro- and macro-scales.

We had microscopes growing up, and I remember spending hours looking at specimens and being fascinated by these miniature forms of theater I observed as a child. When I later moved to the San Francisco Bay Area to go to graduate school, I had access to these fantastic observatories where I could see lunar eclipses, and go on planet-gazing evenings where I could see the rings of Saturn. It's not that it ever coalesced as a single idea in my mind, but I think that the seduction of scale was always something that fascinated me, especially with regard to how the visual, and sensing in general, shapes human consciousness.

That in and of itself is also interesting, because now I actually challenge ocular-centric tendencies through my work, but it did start with the power of the visual and capturing, somehow, those different worlds in some kind of visual form that would prompt a different set of questions.

My dean at the University of Michigan, Bryan Rogers, came from chemical engineering and both the visual and digital arts, and he created opportunities for artists and scientists to come together. And this is still something that I try to do in the programs that I launch. He supported a series of mixers for artists and scientists, through which I met particle physicist Dante Amidei who was a scientist at the university and at the Fermilab. And I think that was really what solidified my interest in science because my conversations with Dante were so inspiring. Conversations with Gordon Kane, who is also a particle physicist were thought provoking. These two physicists were willing to spend hours with artists talking about the nature of the matter of what we're made of.

Exploring the dialectics of mind and body

If you're talking about my art from a kind of meta perspective, I would say I try to explore the dialectics of mind and body, of human and artificial and also of sensing and knowing. A rich set of conversations involving the relationship between mind, body and consciousness have emerged through a variety of philosophical positions over time, including certain Asian traditions and Cartesian dualism, which posits that mind and matter are distinctly separate realms. My interest in this territory springs from new visualizations of the human body made available through medicine, nanotechnology, and genetic engineering, which extends these conversations into the present, where contemporary re-conceptualizations of "humanness" are directly linked to new representations of the body in science. Ironically, this brings us back again to the power of the visual.

And I also try to investigate ways in which dominant culture — and also institutional culture — shape people's understanding of the natural world and shape our understanding of science. I try to employ a lot of photography and microscopy and biomedical imaging technology. So, again, it gets back to the importance of what we see in relation to what we know, or what we think we know. And I use these images to interpret and challenge our perceptions and our conventions of science and the world around us. So we've got objective ways of knowing the world and we've got subjective ways of knowing the world, and I think what I try to do through my work is to challenge both of these and propose something that allows the viewer to ask new questions.

From "The Archive" series. Isomorphic Extension, digital photo, 2012, archival lightbox sculptures, 25.5 inches by 6 feet. Credit: Patricia Olynyk

Art and science coming together has done something rather unique

People sometimes presume that science is one single form of inquiry that follows one single methodology. One of the most interesting arguments I ever heard was between two particle physicists. One of them was saying that in conducting an experiment a researcher needed to remain open to any outcome and that this was really at the heart of discovery. The other physicist said, "No, no — you have to have some sense of what you're looking for or you won't recognize it when you see it." So we think that science, first of all, is one single kind of empirical process. But, I think, even within various scientific methodologies there are numerous variations.

So art is unique in that artists don't typically start with a hypothesis and then structure their practice to prove it. But I think that artistic practice can in and of itself be a form of research and knowledge production. The outcomes tend to be more open-ended, but they're driven by the same drive for inquiry and desire for discovery. And from that perspective I do think it's not that hard for artists to be inspired by science, particularly in new advances in medicine, biotechnology, nanotechnology, cosmology and quantum physics.

I also think it's not that hard for scientists to be inspired by visualizations or creative conceptualizations of what's happening in science. Of course, there are examples of bad collaborations. At worst, the artist gets used as a kind of illustrator by the scientist. And at worst the artist misinterprets and misuses ideas from science that don't advance inquiry and that don't incite reasoned debate, especially about some of the more controversial aspects of science.

But I do think that art and science coming together has done something rather unique. And it seems to me that it's almost the lay audience that's changed the most in all of this.

Science has reached such a broad audience that the kind of chief impact on culture and on artists involves the ability to stimulate new thinking and ways of knowing rather than art necessarily shifting the way that science works (though this can also be the case). But I do think that science's outreach to a broader audience, which frequently happens through art, especially work that addresses the social and/or ethical dimensions of science has fundamentally changed the way that our collective culture thinks about life and the environment.

The NEA is committed to encouraging work at the intersection of art, science and technology through its funding programs, research, and online as well as print publications. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.