8 Tips to Be a Probiotic Pro

Finding "good bacteria"

These days, you'll find probiotics in more places than yogurt and the supplements aisle. "Good bacteria" are turning up in everything from toothpaste and chocolate, to juices and cereals.

"The oddest place I saw probiotics was in a straw," said Dr. Patricia Hibberd, a professor of pediatrics and chief of global health at MassGeneral Hospital for Children in Boston, who has studied probiotics in young children and older adults. "It seemed difficult to imagine how a straw could deliver probiotics in a meaningful way," she said.

Hibberd said she also wasn't a fan of probiotics in bread, because toasting a slice could potentially kill the live organisms. "What also shocks me is the cost of some of these products," she said.

Putting probiotics into foods that don't naturally have the beneficial bacteriamight not make these products healthier, higher quality or worthwhile additions to the diet, she said.

"At some level, there's more hype about probiotics than there should be," Hibberd told LiveScience. "The enthusiasm has gotten ahead of the science."

These facts don't seem to have dampened consumer interest: The Nutrition Business Journal anticipated that U.S. sales of probiotic supplements in 2013 would top $1 billion. [5 Ways Gut Bacteria Affect Your Health]

To separate the reality from the hype, here are eight tips to keep in mind before buying probiotics in foods or taking them as supplements.

Probiotics are not regulated like drugs

"I think probiotics in supplements are generally pretty safe," Hibberd said. Even so, probiotics sold as dietary supplements do not require FDA approval before they are marketed, and do not go through the same rigorous testing for safety and effectiveness as drugs do.

Although supplement makers cannot make disease-specific health claims without the FDA's consent, manufacturers can make vague claims, such as saying that a product "improves digestive health." Also, there are no standardized amounts of microbes or minimum levels required in foods or supplements.

Mild side effects are possible

When people first start taking probiotic supplements, there's a tendency to develop gas and bloating in the first few days, Hibberd said. But even when this happens, these symptoms are usually mild, and they generally go away after two to three days of use, she said.

All foods with probiotics are not created equal

Dairy products typically have the most probiotics, and the amount of live bacteria in these foods is quite good, Hibberd said.

To get billions of good bacteria in a serving, choose a yogurt labeled "live and active cultures," she said. Other probiotic-rich foods include kefir, a fermented milk drink, and aged cheeses, such as cheddar, Gouda, Parmesan and Swiss.

Beyond the dairy case, probiotics are also found in pickles packed in brine, sauerkraut, kimchi (a spicy Korean condiment), tempeh (a soy-based meat substitute) and miso (a Japanese soybean paste used as a seasoning).

Then there are foods that seemingly jumped on the probiotics bandwagon. They aren't naturally fermented or cultured, but may supply some live organisms; these foods include probiotic-enriched juices, cereals and snack bars.

Although the majority of probiotics found in foods are safe for most people, the bigger concern is whether the organism is actually present when the person consumes the food, Hibberd said. In some cases, the organism may have decayed, making it less active than it could be and less able to offer health benefits, she said.

Probiotics might not be safe for everyone

There are definitely some people who should avoid probiotics in foods or supplements, Hibberd said. These might include individuals with weakened immune systems, such as cancer patients who are receiving chemotherapy. The risks are also increased in people undergoing organ transplants, and for people who have had much of their gastrointestinal tract removed because of disease.

People who are hospitalized and have central IV lines should avoid probiotics, as should people who have abnormal heart valves or who need heart valve surgery, because there is a small risk of infection, Hibberd said.

Pay attention to expiration dates

Live organisms can have a limited shelf life, so people should use probiotics before their expiration dates to maximize the potential benefits. To prevent the organisms from losing their potency, product labels or manufacturer's websites may indicate proper storage information; some supplements needs refrigeration, or should be kept at room temperature or in a cool, dark place.

Read product labels carefully

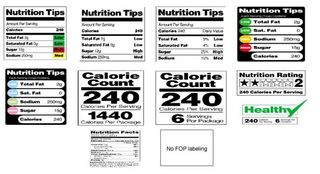

The amount of probiotics in a food product is often unclear. Ingredient labels may reveal the organism's genus and species, but will not include a microbe count.

Labels on supplements should specify the genus, species and strain, in that order. For example, a label might say, "Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG." Microbe counts are listed as colony-forming units (CFU), which are the number of live organisms in a single dose, typically in the billions.

Follow package directions for instructions on proper dosage, frequency and storage. In her studies on probiotics, Hibberd advises participants to open up supplement capsules and sprinkle the contents into milk.

Supplements tend to be pricey

Probiotics are some of the most expensive dietary supplements, with one dose often costing more than $1 a day, according to a 2013 study by ConsumerLab.com. And a higher price might not necessarily reflect a higher-quality supplement, or a reputable manufacturer.

Select the organisms needed for your medical condition

For people who are looking to help prevent or treat a specific health concern with probiotics, Hibberd recommends finding a high-quality study published in a reputable medical journal that shows positive results. Use the product and organism mentioned in the research at the dose, frequency and length of time described.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Cari Nierenberg has been writing about health and wellness topics for online news outlets and print publications for more than two decades. Her work has been published by Live Science, The Washington Post, WebMD, Scientific American, among others. She has a Bachelor of Science degree in nutrition from Cornell University and a Master of Science degree in Nutrition and Communication from Boston University.