Life Blooms on Swirling Ocean Current (Photo)

A bright aqua bloom of phytoplankton dances in the Leeuwin Current, off the coast of Western Australia, in a newly released satellite photo.

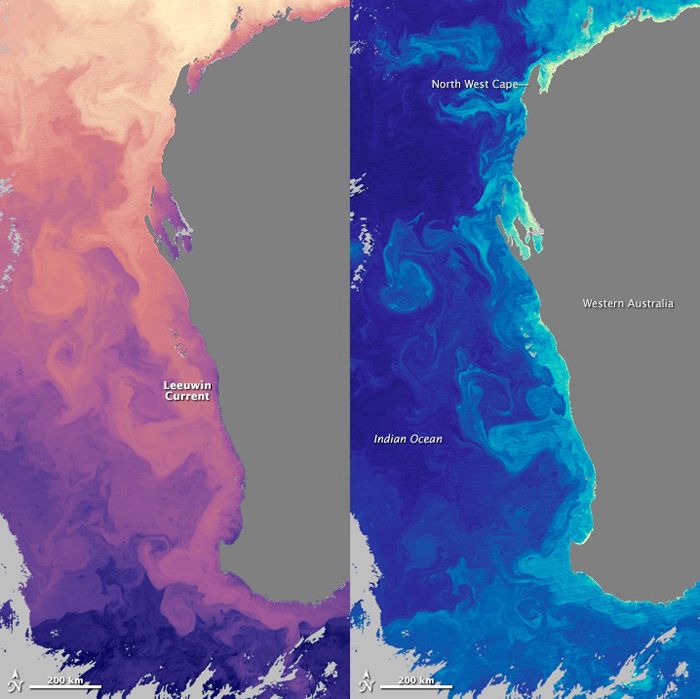

On the left of this image, created by NASA's Earth Observatory, is a map of sea surface temperatures on June 6. The warmer colors outline the Leeuwin Current, which flows from the equator toward the North Pole, bringing with it an injection of warm, tropical water.

On the right is a map of chlorophyll concentration, also from June 6. The light blue, green and yellow colors indicate areas of greater chlorophyll, which highlights spots where photosynthetic phytoplankton is blooming in the water.

Phytoplankton paradox

It may seem natural that microscopic algal life would congregate in the warm waters, but the Leeuwin Current actually puts a damper on nutrients off the coast of Western Australia. The current carries few nutrients itself, and its warmth prevents the circulation of nutrient-rich cooler waters from the ocean floor toward the surface, according to the Earth Observatory.

So why was the current full of phytoplankton on June 6? The answer, according to several studies, is in the eddies. These slow swirls of water create phytoplankton-friendly conditions. According to a 2008 paper published in the Journal of Geophysical Research, eddies may cause local upwelling of nutrients right along the continental shelf. Seasonal changes in the water column may also play a role.

Ocean eddies could also serve as an important transportation system for fish larvae, the Government of Western Australia's Department of Fisheries stated.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Crucial current

The Leeuwin Current is important to people, too. The warm water it brings to Western Australia's coast helps keep winter temperatures from plunging too low, while the warm, moist ocean air also promotes rainfall, according to the Department of Fisheries.

Without the current, Western Australia would be much more arid, and much less appealing. Divers can frolic in the clear coastal waters even in winter (if they wear wetsuits), thanks to the warmth of the current.

The images seen here were made with data from NASA's Moderate-Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer, which was originally published on NASA's Ocean Color Web database.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.