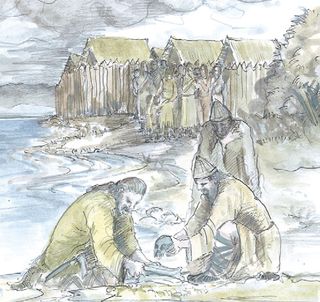

Children's skulls found at the edges of Bronze Age settlements may have been a gruesome gift for the local lake gods.

The children's skulls were discovered encircling the perimeter of ancient villages around lakes in Switzerland and Germany. Some had suffered ax blows and other head traumas.

Though the children probably weren't human sacrifices killed to appease the gods, they may have been offered after death as gifts to ward off flooding, said study co-author Benjamin Jennings, an archaeologist at Basel University in Switzerland.

Lake dwellers

Since the 1920s, archaeologists have known that ancient villages dotted Alpine lakes in Switzerland and Germany. However, it wasn't until the 1970s and 1980s that many of the sites were excavated, yielding hunting tools, animal bones, ceramics, jewelry, watchtowers, gates and more than 160 dwellings. Tree rings on wooden artifacts from the sites suggest people lived there at different periods between 3,800 and 2,600 years ago. [Mummy Melodrama: Top 9 Secrets About Otzi the Iceman]

The Bronze Age lake dwellers regularly faced flooding. Whenever lake levels rose, they would pick up and move to dry land, only to return once the waters receded. To adapt to this watery threat, the people built houses on stilts or on sturdy wooden foundations, and created palisades, or fences, made from bog pine, the researchers wrote in the June issue of the journal Antiquity.

But in addition to finding evidence for such architectural adaptations, archaeologists also unearthed more macabre details of life (and death): children's skulls and skeletal remains encircling the villages at the palisade edges. Many of these ancient skulls were placed there long after their initial burial, at a time when the settlements experienced the worst inundation from rising lake levels, the researchers wrote.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Gift to the gods

In the current study, Jennings and his colleagues took a closer look at the fossil skeletons.

Most were from children under age 10, and though the skeletal remains revealed tooth decay and signs of respiratory ailments, those health troubles would not have been severe enough to warrant a mercy killing, the researchers wrote in the journal article.

The skulls showed evidence of head trauma from battle-axes or clubs, though the injuries don't have the uniformity associated with a ritual killing. As a result, it's more likely the youngsters were felled in warfare, rather than killed as a sacrifice for the gods, the researchers wrote.

Either way, it's clear these weren't ordinary burials, he said.

"Across Europe as a whole there is quite a body of evidence to indicate that throughout prehistory human remains, and particularly the skull, were highly symbolic and socially charged," Jennings told Live Science in an email.

At these sites, "the remains are found at the perimeter of the settlement — not inside and not outside, but at a liminal position on the border between in and out," Jennings added. And at one of the sites, the remains were placed at the high-water mark of the floodwaters. Taken together, the details of the burial suggest the remains were placed as an offering to protect against flooding, Jennings said.

Still, there are many unanswered questions about these mysterious Alpine people.

"There are very few instance or examples of burials in the vicinity of the lake settlements, and so we really do not know where the majority of the lake dwellers are buried, or how they treated their dead," Jennings said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.

Most Popular