'Long Tail' Is Tale of Extinction for Amazing Sea Creatures

Can the mass extinction of the amazing sea creatures called ammonites teach business owners anything about survival?

For small businesses to compete online against a behemoth like Amazon, Internet gurus point owners toward the "long tail" — tiny niches where they can sell specialized products and services. The marketing concept is borrowed from statistics, in which the long tail describes values that skew far from most of the group. Amazon itself benefits from the long tail, by selling books that aren't available in most other stores.

But too much specialization can be a death sentence in the natural world, according to scientists. Sitting at the end of the long tail is thought to contribute to extinction risk. For example, species that can live only in a narrow set of environmental conditions teeter on the edge of survival when climate starts to change, as it inevitably does on Earth.

Now, a new study blames the long tail for the mass extinction of the amazing sea creatures called ammonites. The findings were published June 30 in the journal Geology.

Coiled kraken

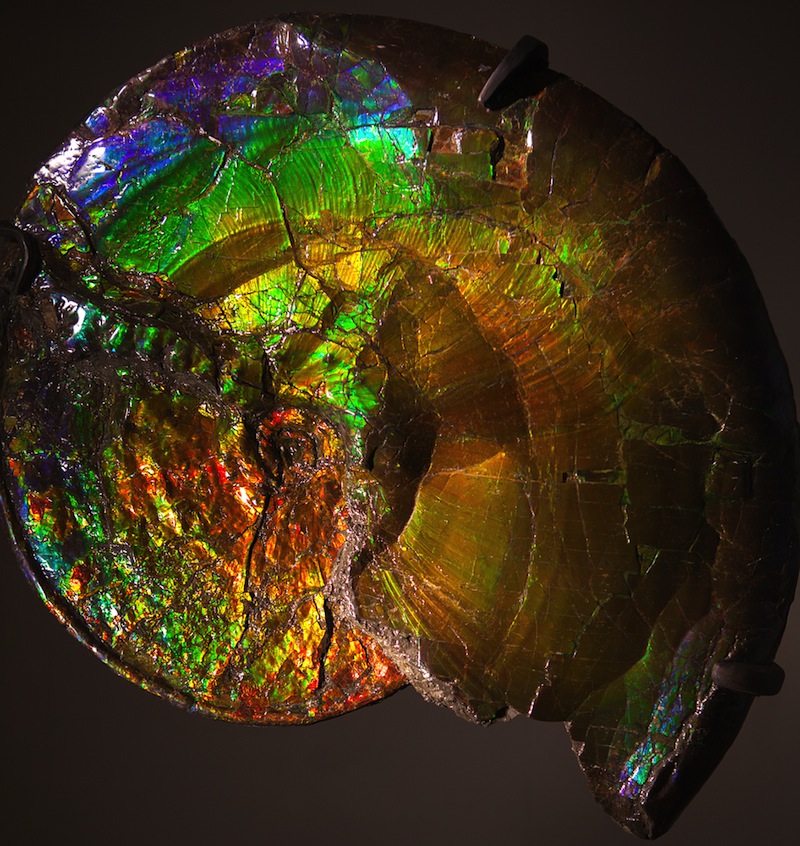

Ammonites were among the masters of the Mesozoic ocean, during the time of the dinosaurs. These squidlike, swimming plankton eaters had sharp beaks and a pearly, protective shell. Their closest modern-day relatives include smart cephalopods such as squid and octopus, but most ammonites looked like their distant modern cousins, the chambered nautilus. The ammonites' tightly whorled shells now light up museum fossil collections, glistening like rainbows.

Despite surviving earlier mass extinctions, the ammonites died off after the massive meteor or asteroid impact at the end of the Cretaceous Period 65 million years ago — the same blast that finished off the dinosaurs. But other species, such as mammals, survived and thrived after the impact's environmental effects cleared. Why some species disappeared, while others spread, is an area of intense interest among scientists. [Wipe Out: History's Most Mysterious Extinctions]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Everybody wonders why some organisms survive and some go extinct," said lead study author Neil Landman, a curator at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

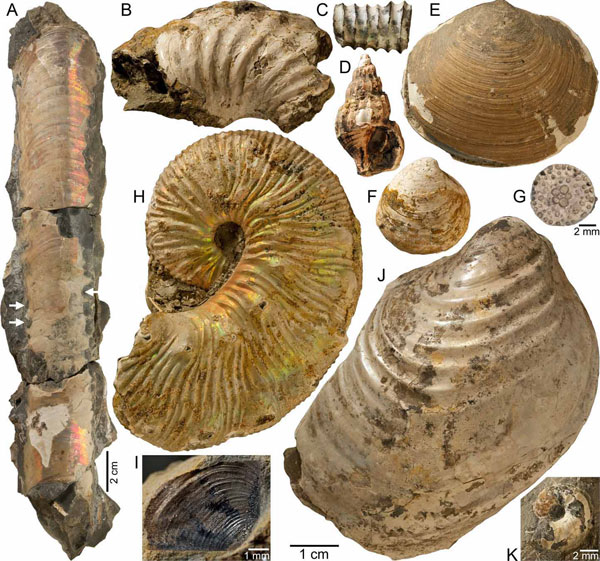

Recently, Landman decided to find out why the ammonites disappeared. To do so, Landman and his co-authors tallied the 30 vanished ammonite species (and one nautilus) and plotted out their geographic range 65.5 million years ago, accounting for changes in geography and climate. The creatures were so abundant that thousands of their fossils are found in rocks all over the world.

"By any measure taken at the time, one would have said they were in great shape," Landman said. "Yet they turned out to be vulnerable."

Too many nooks

Here's where businesses on the long tail might want to pay attention.

The fossils revealed that most ammonites lived in environmental niches. That is, about half of all ammonite species from this time are found in only one or two spots. And the more exquisite the ammonite's niche, the less likely it was to survive the Cretaceous apocalypse. These geographically vulnerable species quickly vanished after the impact.

But ammonites such as Eubaculites and Discoscaphites, whichwere widespread before the impact, survived thousands of years after the meteorite hit, Landman said. There were six species that lingered, though all eventually succumbed to extinction.

"There was a eureka moment," Landman said. "The moment I saw the distribution it clicked in my mind and I said, 'Oh, wow, this may be the explanation for why they go extinct.' I didn't anticipate this outcome."

The ammonites petered out due to more than one disastrous change caused by the impact, Landman said. Ocean acidification likely dissolved the shells of their microscopic young, which float on the ocean's surface early in life, he said. Fossil records also show the impact devastated plankton species, the primary food source for adult ammonites. "It may have only lasted 100 years, but that would have effectively starved some of the ammonites," he said.

Landman's team now plans to dial back the fossil database even further, looking 2 million years before the impact. With this window open, the researchers will explore another contentious area in the Cretaceous — whether the meteor was the killer blow, or the straw that broke the camel's back. Some evidence suggests many creatures were already on the decline at the end of the Cretaceous, well before the impact set off a climate disaster.

Landman wondered, "If the impact had happened 2 million years earlier, could you have predicted the same result? Or would the ammonites have been in a much stronger position? We want to turn back the clock now and find out."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.