'Sonic Boom' Earthquake Shatters Expectations

One of the world's deepest earthquakes was also a rare supersonic quake, upending ideas about where these unusual earthquakes strike.

Only six supersonic (or supershear) earthquakes have ever been identified, all in the last 15 years. Until now, they all showed similar features, occurring relatively near the Earth's surface and on the same kind of fault. But last year, a remarkably super-fast and super-deep earthquake hit below Russia's Kamchatka Peninsula, breaking the pattern.

"This was very surprising," said Zhongwen Zhan, lead author of the study, published today (July 10) in the journal Science. "It's not only deep, it's supershear, and it's also quite small."

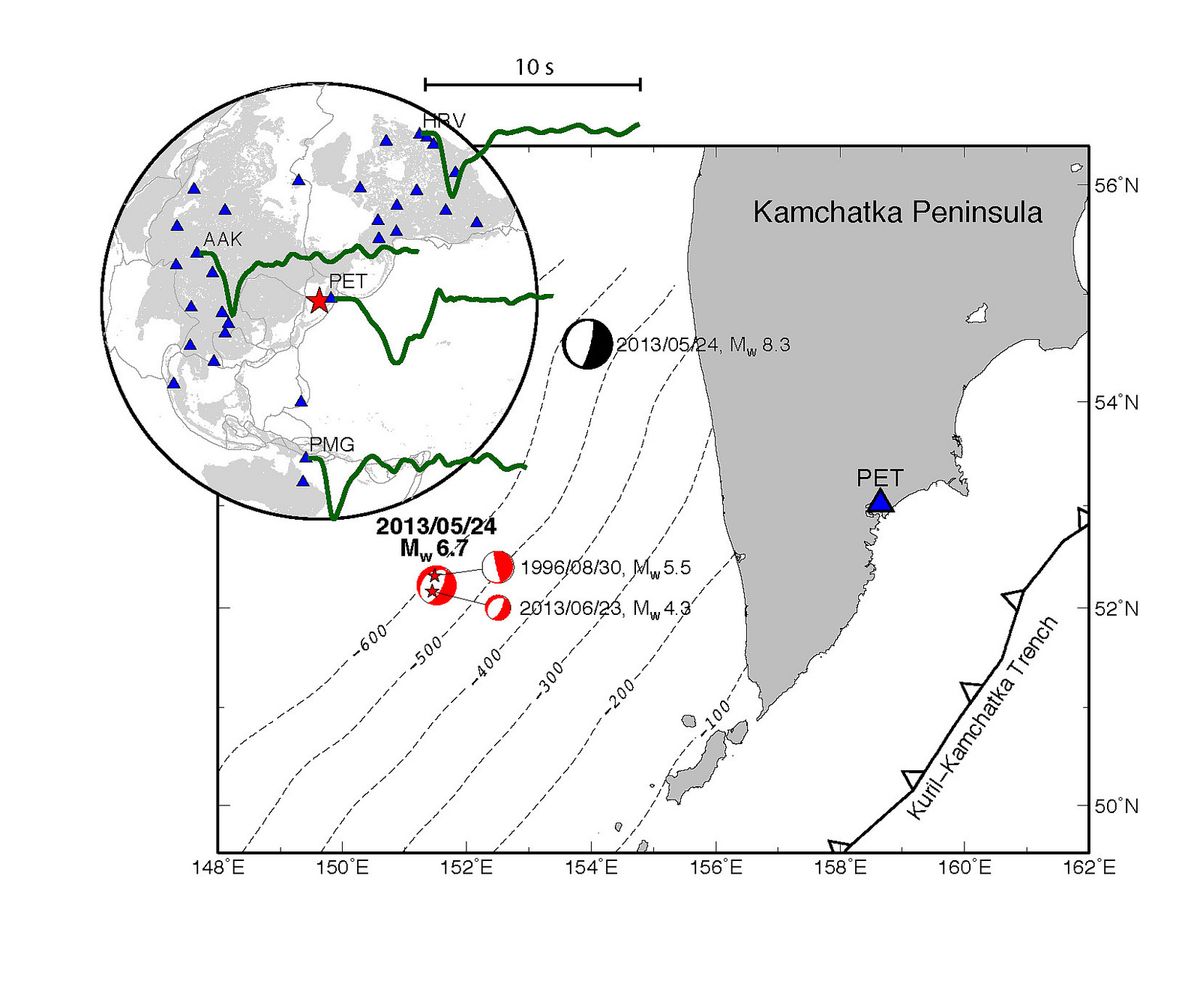

The weird earthquake struck May 24, 2013, about 398 miles (642 kilometers) beneath the Sea of Okhotsk offshore of the Kamchatka Peninsula. The magnitude-6.7 quake was an aftershock to the largest deep earthquake on record, a magnitude 8.3 that also hit May 24. [Image Gallery: This Millennium's Destructive Earthquakes]

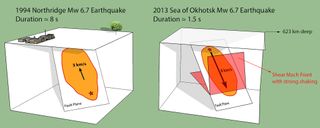

The shaking provided the first sign that this was a strange quake. Earthquakes of similar size, such as the 1994 Northridge quake in Los Angeles, shimmy for seven to eight seconds. But this magnitude-6.7 temblor lasted for just two seconds.

After dredging up all the available seismic recordings, Zhan and his co-authors realized the earthquake was extremely short because it was extremely fast.

An earthquake occurs when two sides of a fault rip apart, opening up like a zipper. Faults can slide side-by-side or up-and-down, or a combination of both directions. The event unleashes waves of seismic energy. Certain types of waves called shear waves usually travel faster than the rupture unzips, but in supershear earthquakes, the rupture catches the shear waves.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When the rupturing fault moves faster than the shear waves, the waves of energy pile up like the Mach cone surrounding a jet flying faster than the speed of sound, creating a phenomenon akin to a seismic sonic boom.

The Okhotsk quake's rupture speed clocked in at a zippy 5 miles per second (8 km/s), said Zhan, a seismologist at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, California. Regular earthquakes, at shallower depths, break loose at about 2.2 miles per second (3.5 km/s), he said.

'U' is for unique

Until now, seismologists had never documented a super-fast earthquake at such extreme depths. Nor have they seen supershear earthquakes on this kind of fault.

Previously, the super-fast quakes were on strike-slip faults, where two slabs of the Earth slide past each other with no up-and-down motion. But the Okhotsk earthquake was in a subduction zone, where a fault thrusts one of Earth's tectonic plates down below another plate.

Zhan said he thinks the new earthquake will upset models of supershear earthquakes and their potential for dangerous shaking. The seismic sonic boom effect can increase the effects of surface shaking by two to three times over regular earthquakes, researchers think. But until now, no one thought that thrust-type faults could go supersonic.

"If a shallow earthquake such as Northridge goes supershear, it could cause even more shaking and possibly more damage," said Zhan. "The shear Mach cone carries very strong shaking," he told Live Science.

Zhan said the earthquake would also help researchers better understand super-deep earthquakes. There are still huge unknowns about why these earthquakes take place, he said.

"We still don't know why earthquakes can do supershear," Zhan said. "And we still don't know why deep earthquakes occur. But this surprising observation tells us something about deep earthquakes."

The study throws a wrinkle into the debate over whether deep earthquakes are fundamentally different from earthquakes closer to Earth's surface, said Thorne Lay, a seismologist at the University of California, Santa Cruz, who was not involved in the research.

Lay isn't convinced the Okhotsk earthquake was a supershear quake. "It's a reasonable interpretation, but there's a lot of complexity in the [seismic] signals," he said. Other kinds of shaking seen in deep earthquake zones could produce a similar effect.

Deep quakes hit where the behavior of rocks fundamentally changes: They transition from breaking apart like bricks, to slowly flowing like warm plastic (called ductile deformation). Researchers actively debate how rocks can fracture apart in earthquakes at these depths.

"This is one of the cleanest, sharpest ruptures we've ever seen," Lay said. "If it is a supershear earthquake, it would be extremely cool."

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.