Medieval Italian Skeleton's Surprising Diagnosis: Livestock Disease

A sip of unpasteurized sheep or goat's milk may have spelled doom for a medieval Italian man.

A new genetic analysis of bony nodules found in a 700-year-old skeleton from Italy reveal that the man had brucellosis, a bacterial infection caught from livestock, when he died. It's not clear if the disease killed the man, but he likely would have suffered from symptoms such as chronic fatigue and recurring fevers, according to the researchers who analyzed the bones.

This medieval Italian man joins many other long-dead people in getting a postmortem diagnosis of brucellosis. Signs of the disease have been found in skeletons from the Bronze Age and earlier. In fact, the disease predates modern humans: In 2009, researchers reported possible signs of brucellosis in a specimen of the human ancestor Australopithecus africanus, who lived more than 2 million years ago. [10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

Disease hunters

The brucellosis-infected Italian came from Sardinia. He was buried in a medieval village called Geridu, which was abandoned sometime in the late 1300s, and was probably between 50 and 60 years old when he died.

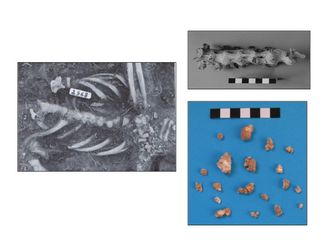

Archaeologists found 32 bony nodules scattered in the man's pelvic region, the largest about 0.9 inches (2.2 centimeters) in diameter. Such nodules are often a sign of tuberculosis, a lung infection caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuberculosis is the most common culprit in cases of calcified nodules, study leader Mark Pallen, a microbial genomist at Warwick Medical School in England, said in a statement.

Pallen and his colleagues sampled one of the nodules and subjected it to a process called "shotgun metagenomics." Instead of searching for a particular DNA signature, shotgun metagenomics takes the approach of simply sampling all the DNA present, just to see what turns up.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To the researchers' surprise, the man did not have tuberculosis. Instead, the bony nodule held the DNA signature of the bacterium Brucella melitensis, the microbe that causes brucellosis.

Animal malady

Brucellosis can be transmitted from livestock to humans in several ways. One possibility is that the man caught the disease from direct contact with animals — perhaps while slaughtering a sheep or delivering a newborn lamb. Or he could have gotten the disease from drinking unpasteurized milk or eating unpasteurized cheese. The Brucella strain that infected the man was a close relative of modern Italian strains, the researchers found, and sheep and goat herding have long histories in the region.

Brucellosis is also called Mediterranean fever. It still affects more than 500,000 people around the world yearly, though livestock vaccination and dairy pasteurization have hampered its spread.

Today, antibiotics are used to treat people with brucellosis, and no more than 2 percent of infected people die from the disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In its chronic, untreated form, the disease causes muscle and joint pain, fatigue and depression. The deadliest symptom of the disease is endocarditis, the swelling of the lining of the heart.

The method of diagnosing the medieval man's brucellosis could be used to uncover other ancient diseases, the researchers said. By not honing in on specific DNA signatures, researchers can cast a wider net, they wrote in their report of the case published today (July 15) in the journal mBio.

The team is now using the technique to test an array of samples, from ancient Hungarian and Egyptian mummies to the lung tissue of an early medieval French king, the researchers said in a statement.

"We're cranking through all of these samples, and we're hopeful that we're going to find new things," Pallen said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular