Don't Take Niacin for Heart Health, Docs Warn

Niacin, or vitamin B3, is too dangerous and should not be used routinely by people looking to control their cholesterol levels or prevent heart disease, doctors say. The warning comes following recent evidence showing the vitamin does not reduce heart attacks or strokes, and instead is linked to an increased risk of bleeding, diabetes and death.

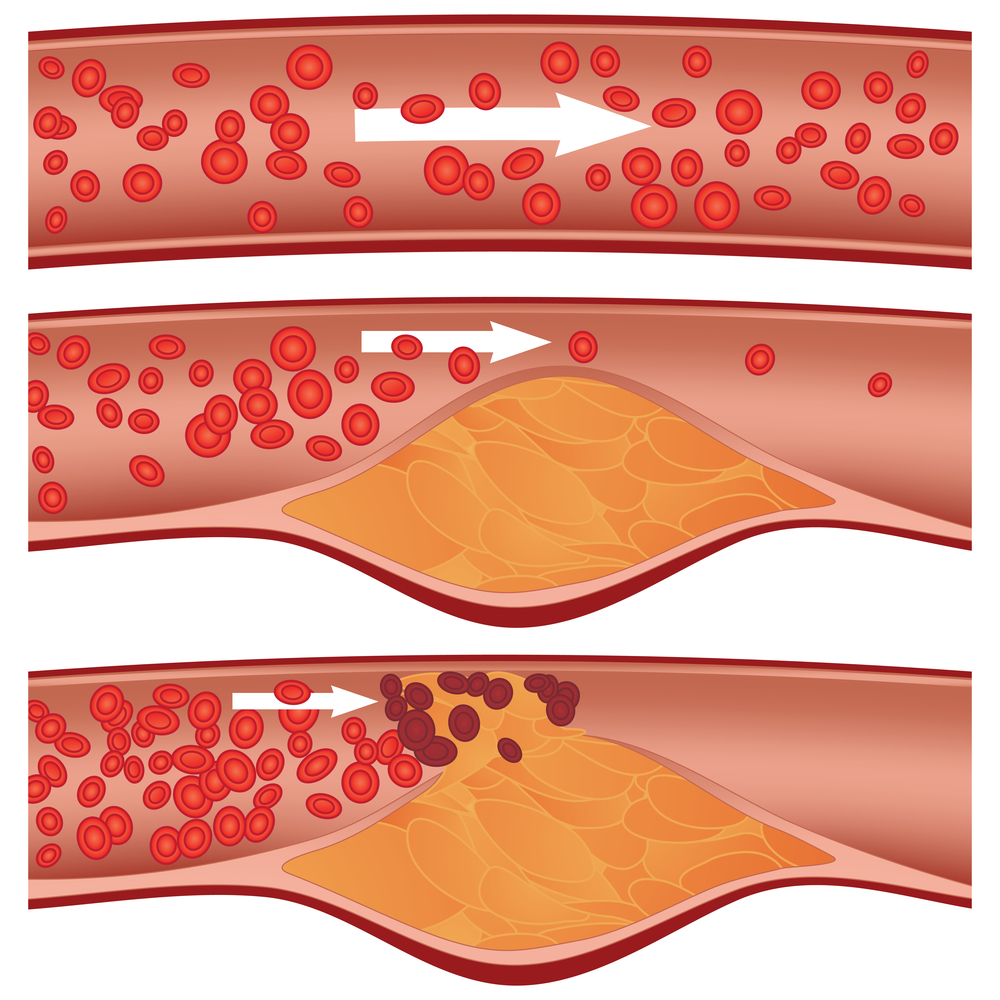

Niacin has long been used to increase people's levels of high-density lipoprotein (HDL), or the "good" cholesterol, and has been a major focus of research into heart disease prevention for several decades. However, clinical trials have not shown that taking niacin in any form actually prevents heart problems. Considering the alarming side effects of niacin, researchers now say the vitamin shouldn't even be prescribed anymore.

"There might be one excess death for every 200 people we put on niacin," said Dr. Donald Lloyd-Jones, a cardiologist and chair of preventive medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. "With that kind of signal, this is an unacceptable therapy for the vast majority of patients." [8 Tips for Healthy Aging]

The latest and largest study of niacin, which included more than 25,000 people with heart disease, was published today (July 16) in The New England Journal of Medicine. The researchers found that using long-acting niacin to raise the HDL cholesterol level did not result in reducing heart attacks, strokes or deaths. The results were presented prior to publication last year, after which the manufacturer of the niacin medication used in the study, Merck & Co., said it would stop selling the drug.

The study also found some unexpected and serious side effects. People who took niacin were more likely than people taking a placebo to experience liver problems, infections and bleeding in various body areas including the stomach, intestines and brain.

Niacin was also linked with more hospitalizations among diabetic patients and the development of diabetes in people who didn't have it at the beginning of the study.

The Merck drug was a combination of niacin and laropiprant, a drug that prevents the facial flushing that can be caused by high doses of niacin. However, the study researchers said the side effects were consistent with the problems seen in previous studies of Niacin alone, and that the new findings "are likely to be generalizable to all high-dose niacin formulations."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"That particular medication is not being sold anymore, but the issue is that there's still an awful lot of niacin prescriptions being given to patients, whether that's plain niacin or extended-release niacin," Lloyd-Jones told Live Science.

"When you look at the totality of the data, particularly with this largest and the most recent trial, it suggests that it's actually niacin itself that's the problem, and not this specific niacin-laropiprant combination," said Lloyd-Jones, who wasn't involved with the new study.

The popular rise of niacin

Prescriptions for niacin have jumped in recent years, tripling over just eight years to reach 700,000 prescriptions monthly in the United States by the end of 2009, researchers have found. Of all niacin prescriptions written in 2009, 80 percent were for Niaspan, a slow-releasing niacin tablet made by Abbott Laboratories, according to a study published last year.

However, the rate of niacin prescriptions may have decreased after the results of several studies were released, Lloyd-Jones said.

Niacin can also be bought over the counter as a supplement. These supplements may have their own issues because vitamin products are not regulated in the same way that pharmaceutical products are. "It may come with other things in the preparation that we don't know about, and could potentially enhance the toxicity of niacin," Lloyd-Jones said. "Because it is available over the counter, I think it's important for consumers to understand that this signal appears to apply to all types of niacin."

The available evidence suggests that having higher levels of good cholesterol is only a sign of lower risk for heart problems, and trying to artificially raise levels of the good cholesterol doesn't appear to translate into lowering a person's risk of heart problems.

"HDL is a nice marker — if it's higher, you tend to be at lower risk. So if you could manipulate that with healthy lifestyle and physical activity, that's undoubtedly a good thing to do, but we haven't found a drug that will raise HDL in isolation and provide benefit in terms of lower risks," Lloyd-Jones said.

A healthy lifestyle is the first recommendation for lowering LDL, or the "bad" cholesterol, and reducing the risk of heart disease. For people who are not successful in controlling their cholesterol levels by changing their lifestyle, doctors may prescribe statins, which remain the best choice to reduce heart attack and stroke risk, Lloyd-Jones said.

Niacin should only be considered for patients at very high risk for a heart attack and stroke who can't take statins, and for whom there are no other evidence-based options, Lloyd-Jones said.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.