An ancient skeleton unearthed in Israel may contain the oldest evidence of brain damage in a modern human.

The child, who lived about 100,000 years ago, survived head trauma for several years, but suffered from permanent brain damage as a result, new 3D imaging reveals.

Given the brain damage, the child was likely unable to care for himself or herself, so people must have spent years looking after the little boy or girl, according to the researchers who analyzed the 3D images. People from the child's group left funerary objects in the youngster's burial pit as well, the study authors said.

Those signs of care for a disabled person suggest that the roots of human compassion go way back, said Hélène Coqueugniot, an anthropologist at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) at the University of Bordeaux in France, and lead author of the study.

"It is some of the most ancient evidence of compassion and altruism," Coqueugniot said.

Young child

The child's skeleton was first uncovered decades ago in a cave site known as Qafzeh in Galilee, Israel, which also contained 27 partial skeletons and bone fragments, as well as stone tools and hearths. [See Images of the Damaged Skull and Skeleton]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The child, whose sex couldn't be determined, was found with a visible fracture in the skull and a pair of deer antlers placed across the chest.

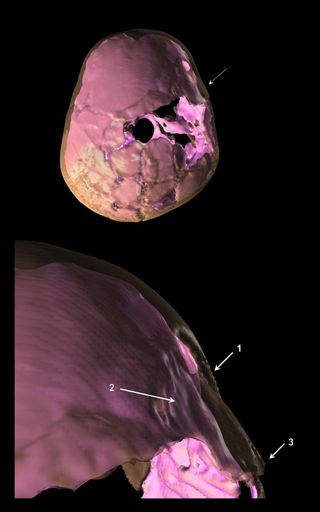

The researchers wanted to know more about the damage to the child's skull, so they created a cast of the interior of it and then used computed tomography (CT) scanning to create a 3D picture of the head.

The images revealed that the child suffered a blunt-force trauma at the front of the skull that created a compound fracture, with a piece of bone depressed in the skull. It wasn't clear whether child abuse or an accident caused the injury, the researchers concluded.

In addition, tooth growth indicated that the youngster was 12 or 13 years old when he or she died, but the child's brain volume was more akin to that of a 6- or 7-year-old — likely because the head trauma permanently halted brain growth, Coqueugniot told Live Science.

The brain injury would have led to difficulties in controlling movements and speaking, as well as caused personality changes and impaired the child's social functioning, the researchers wrote in their study, which was published July 23 in the journal PLOS ONE.

Human compassion?

Yet despite the youngster's severe disability, he or she was apparently cared for, in life and in death. Despite lacking the ability to survive on his or her own, the Paleolithic child lived for several years after the head injury. And when the child died, someone wanted to honor his or her memory by placing the deer antlers in his or her burial — a funerary marker that wasn't found in any of the other burials at the site, Coqueugniot said.

"He was very, very special in this group, and he has a very, very special burial," Coqueugniot said.

The findings are not the oldest example of compassion and care for the disabled in a hominid; a 500,000-year-old fossil human from Sima de los Huesos in Spain shows signs of severe brain deformity starting at birth, but that child still lived to age 5, which mean someone cared for the child despite his or her disorder.

But the Qafzeh child reveals a striking example of compassion and care for the disabled in early modern humans, who are anatomically similar to humans today, said Jean-Jacques Hublin, director of the department of human evolution at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany.

It's not clear that head trauma caused brain development to halt, said Hublin, who was not involved in the study. "There is a large variation in brain size among humans, and this is perceptible already in infancy and childhood," Hublin told Live Science.

Therefore, the child may have simply have started out with a small brain, which would have remained relatively small as he or she grew, he said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.