About 800 years ago, parts of the American southwest experienced cataclysmic levels of violence, with almost every person in the ancient society affected, new research suggests.

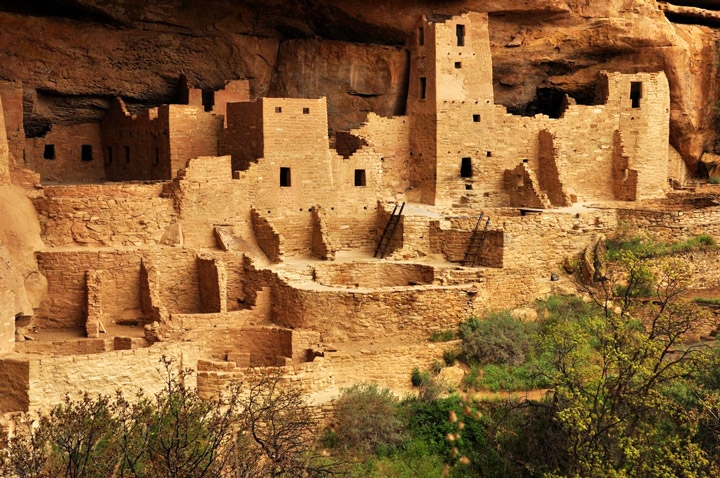

Between A.D. 1140 and A.D. 1180, about nine out of 10 skeletons from around the Mesa Verde region in Colorado show signs of head trauma or blows to the arms, according to a new study published in the July issue of the journal American Antiquity.

"We’ve concentrated on one thing, and that is trauma, especially to the head and portions of the arms," study co-author Tim Kohler, an archaeologist at Washington State University in Pullman, Washington, said in a statement. "That’s allowed us to look at levels of violence through time in a comparative way." [Fight, Fight, Fight: The History of Human Aggression]

Researchers are unsure why society in this region took a turn for the worse around this time, while ancient inhabitants further south in New Mexico lived relatively peacefully. The new findings shed light on why the ancient settlers around the Mesa Verde region mysteriously vanished over the course of only three decades in the late 1200s.

Ancient baby boom

In a study earlier this year analyzing the same burial plots, Kohler and his colleagues found that from A.D. 500 until about 1300, the ancient southwest experienced a prolonged baby boom. During that period, each woman had an average of more than six children in her lifetime, a higher fertility rate than is seen anywhere else in the modern world. A shift from a nomadic existence to a settled agricultural lifestyle, and specifically plumper, more easily cultivated maize, may have led to this surge in population, the researchers hypothesized.

The growing populations spawned more complex, sophisticated and specialized societies around the northern Rio Grande, in what is now New Mexico. The Rio Grande dwellers shifted from kin-based social networks to affiliating with everyone from their pueblo. Larger pan-pueblo associations, such as medicine societies, also flourished. The ancient inhabitants also developed a specialized expertise in crafts, such as shaping obsidian arrow points, which allowed them to trade across larger pueblo networks.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Around the Rio Grande, the population boom may have ushered in more peaceful ways of living, because people in the specialized society were more reluctant to wage war. If the arrow maker, the beer brewer, the weaver and the potter all need each other's goods to survive, it doesn't make sense to fight, the researchers said.

More people, more problems

But further north, in what is now modern-day Colorado, people didn't adapt well to the denser population environment. Few people developed specialized skills, which meant that each person likely looked out for him- or herself.

"When you don't have specialization in societies, there's a sense in which everybody is a competitor because everybody is doing the same thing," Kohler said.

A wave of settlers from further south didn't help matters. People who lived in the Chaco Canyon civilization attempted to expand into the Mesa Verde region following a drought in the mid-1100s.

"They were resisted," Kohler said in a statement, "but resistance was futile."

For a while, the wealthiest people may have stuck around because they had the most fertile spots, even though people in those pueblos were probably leaving as well. Older people, "who weren’t so anxious to move as the young folks who thought, ‘We could make a better living elsewhere,'" may also have been amongst the last holdouts, Kohler said.

In the final days of those settlements, the remaining few pueblos were likely manned by just a few older people, making them especially vulnerable to raids.

And in the end, the settlements were completely abandoned.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitterand Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.