Biomedicine, Microscopy and the Art of Patricia Olynyk (Gallery)

Paulette Beete, NEA senior writer-editor, contributed this article as part of partnership between NEA and Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Visual artist Patricia Olynyk uses the tools of science — microscopy and biomedical imaging — to create installations that explore how our senses help us understand our physical environment.

For example, in The Archive — a series of photographs and light box sculptures that places historically valuable anatomical models, gynecological instruments and prosthetic devices in historical context — Olynyk examines how our relationship with the human body changes when we view it as an assemblage of parts rather than as a whole.

Olynyk has exhibited her work at the Brooklyn Museum, Museo del Corso in Rome, the Saitama Modern Art Museum in Japan, and the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C. She has also held multiple residencies at the College of Physicians in Philadelphia, Canada's Banff Center for the Arts and at the Pyramid Atlantic Center in Maryland.

The following is a series of six images from the artist's work.

You can read Olynyk's interview, where she shares her inspirations for her unique pieces, in "Science As Art: Soundscapes, Light Boxes and Microscopes (Op-Ed)."

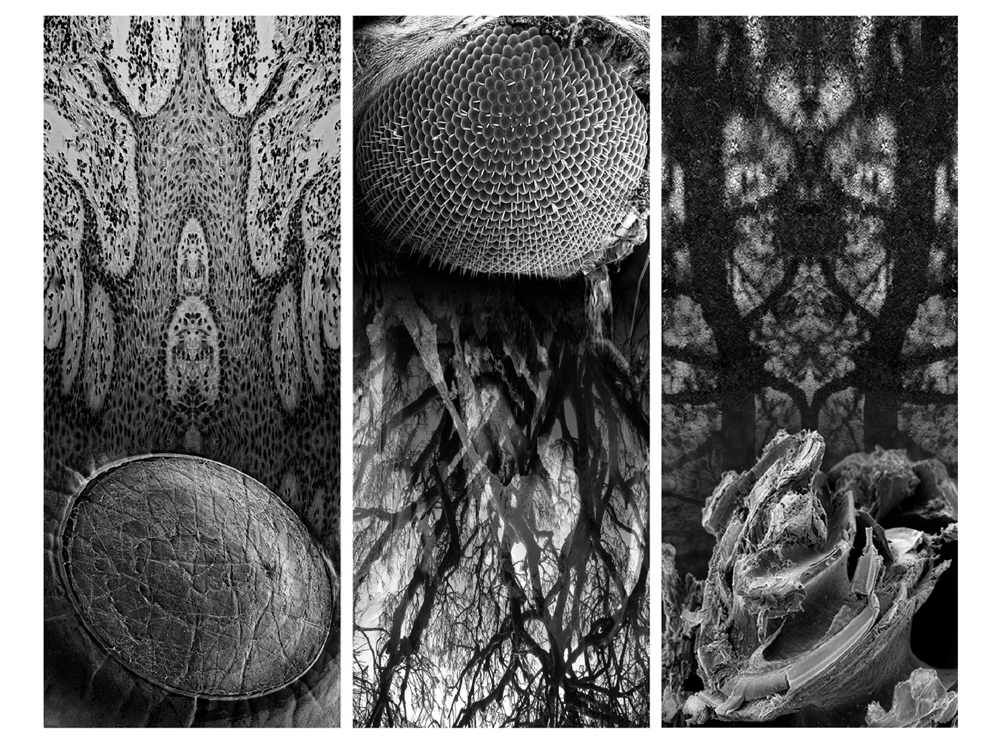

Orb2 from Sensing Terrains

Freed from the confines of scale and context, sensory organs and garden details become hybrid "landscapes" where viewers can travel through tastebuds and nasal epithelial cells into a scramble of roots, reminiscent of complex vascular systems. Some of the images from the Sensing Terrains: Cenesthesia series have been printed in a dramatic chiaroscuro black and white, while others, which incorporate Olynyk's own retina scans are tinted in electric orange and blood red. Orb II, digital photo, 2006, 22.5" x 61" Part of Sensing Terrains installation in rotunda of National Academy of Sciences, Washington DC. Orb II is now in the permanent collection of the Center for Biotechnology, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Perception in art

Multi-channel projections on large CNC-routed tiles and multi-faceted sound pulled from high summer Rocky Mountains recordings have produced a exhibit which draws on the human senses. The installation's muse is night sky preservation.

Cenesthesia Series I

From the Cenesthesia series in the installation Sensing Terrains. In response to a technology mediated world increasingly desensitized to physical sensation, the Sensing Terrains: Cenesthesia series calls on viewers to expand their awareness of the worlds they inhabit, whether those worlds are their own bodies or the spaces that surround them. This multi-media installation focuses on modes of sensation —integrating magnified images of sense organs with macro-images of garden environments designed to heighten sensate experience. Sensing Terrains: large-scale installation in rotunda of National Academy of Sciences, Washington D.C., 10' x 44", 2006.

Cenesthesia II

From the Cenesthesia series in the installation Sensing Terrains. Cenesthesia is "the general feeling of inhabiting one's body that arises from multiple stimuli from various bodily organs." Scanning electron micrographs that Olynyk creates herself represent a variety of specimens, including human corneas (representing sight), wild mouse taste buds and olfactory epithelia (representing taste and smell), guinea pig cochlea (representing sound) and drosophila feet (representing touch). This eclectic array deliberately mixes species to stress that the nature of being sensate is not uniquely human. The sensory experience in the installation is intensified by an interactive and evocative soundscape. Triggered at various locations throughout the installation, sounds drawn from recordings made by the artist in Japan evoke blood coursing through the body, a heart beat and the trancelike hum of Buddhist chants. Sensing Terrains: large-scale installation in rotunda of National Academy of Sciences, Washington DC, 10' x 44", 2006.

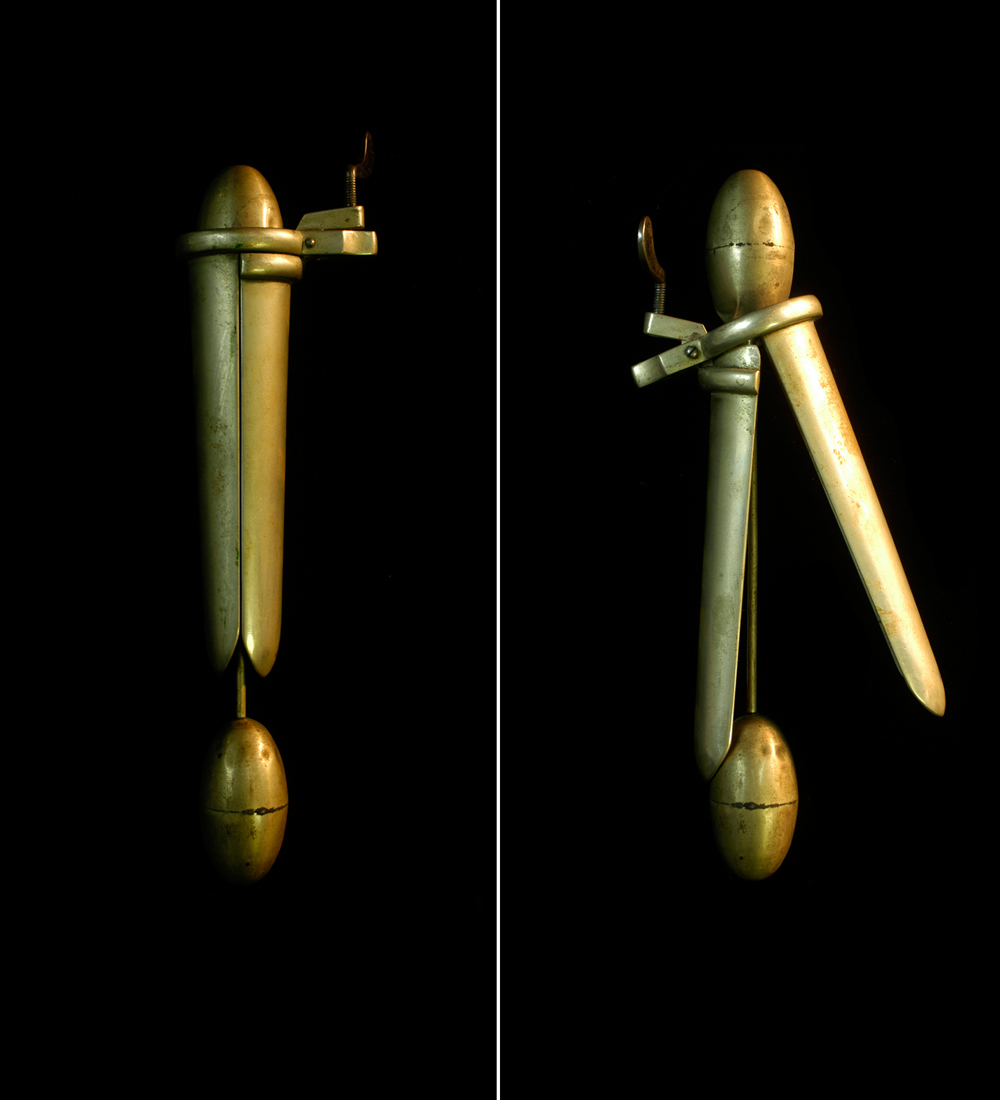

Probe I and II

The Archive mines a vast inventory of anatomical models, flap anatomies, gynecological instruments and prosthetic devices collected for their unique historical value. These re-contextualized images recall the human desire to fetishize and even anthropomorphize objects to supplement or probe the human body. Four distinct bodies of work represented through a series of photographs and lightbox sculptures draw together humans' historical and modern desires to augment, control and manipulate our corporeal selves. This project also brings into the fore some of the more controversial aspects of the history of science and medicine. Probe I + II, 57" x 24" (each), 2011. From The Archive series.

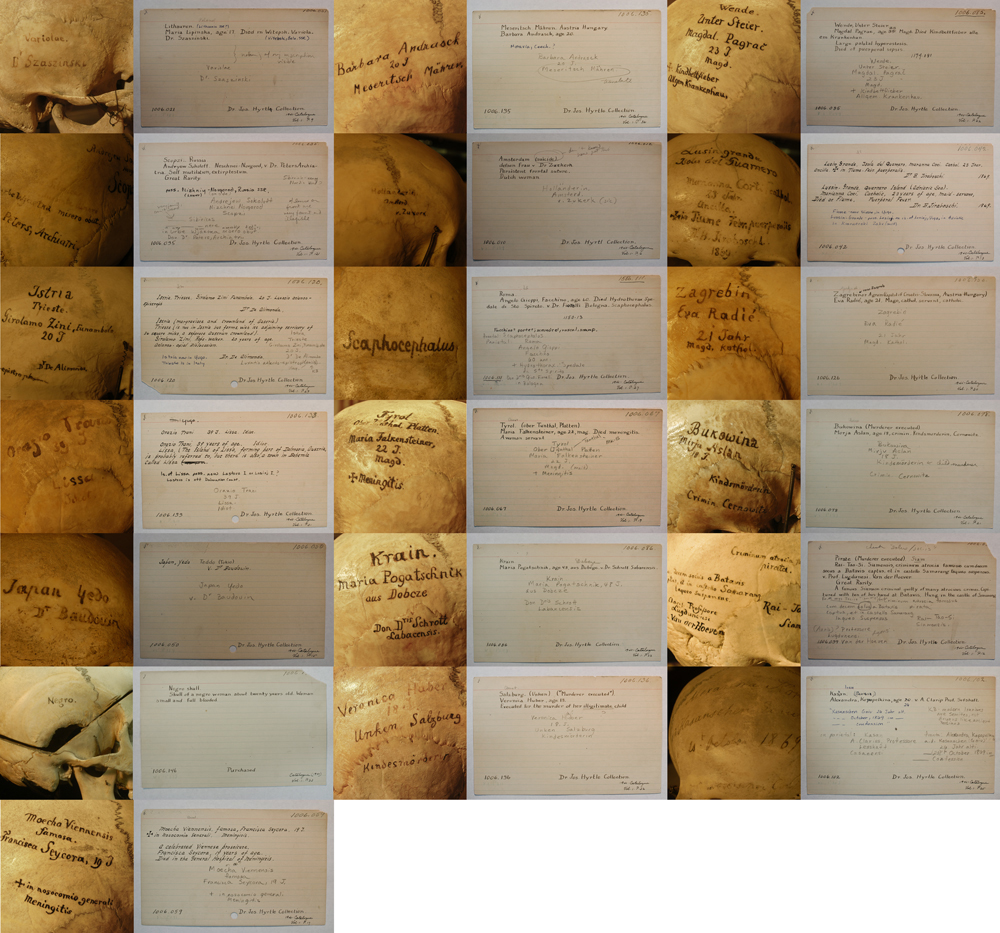

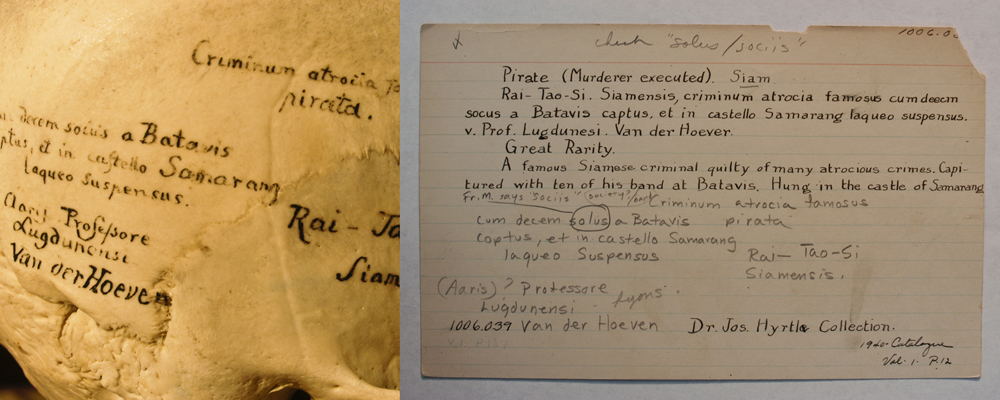

The Mutable Archive

The Mutable Archive — photographs of a collection of human skulls and their accompanying archive cards from the Mutter Museum at the College of Physicians in Philadelphia — represent a series of small memorials. They portray an eclectic array of outcasts, eccentrics, notorious characters, "homo-delinquens" and anomalous individuals. Their individual inscriptions — the post-mortem skull tattoos etched into each — offer a range of interpretations related to personhood, individuality, and humanness. The Mutable Archive, 44" x 47", 2012.

The Mutable Archive Detail 2

The Mutable Archive is a collaborative project that enlists a community of writers, scholars, historians, medical ethicists, philosophers, and even a spiritual medium who will each create a speculative or fictional biography — one for each subject. Archival data, factual errors, personal biases and the writers' own conjectures and longings will guide them as they engage their own processes of history and identity construction, engaging, in their own ways, the illusory nature of truth. The Mutable Archive, 2012 (detail).

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.