Computer Games Better Than Medication in Treating Elderly Depression

Computer games could help in treating older people with depression who haven't been helped by antidepressant drugs or other treatments for the disorder, researchers say.

In a study of 11 older patients, researchers found playing certain computer games was just as effective at reducing symptoms of depression as the "gold standard" antidepressant drug escitalopram. Moreover, those patients playing the computer games achieved results in just four weeks, compared to the 12 weeks it often takes with escitalopram (also known by its brand name, Lexapro).

The computer games even improved what researchers call executive functions more than the drug did, according to the study. These functions are the thinking skills used in planning and organizing behavior, and their impairment has been linked to depression in elderly patients.

The findings suggest computerized therapy could also help treat people with other brain disorders, scientists added.

However, the findings regarding depression are important, because clinical depression affects many older adults. "Depression is a serious and at times life-threatening illness," said lead study author Sarah Shizuko Morimoto, a research neuropsychologist at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York. "This is a biological illness of the brain, no different from any other illness, and it necessitates treatment." [7 Ways Depression Differs in Men and Women]

Antidepressant drugs have side effects that may make people wary of taking them, but not treating the illness can have even more serious consequences, Morimoto said.

However, antidepressant drugs often do little to help elderly patients. "Only roughly one-third of depressed elderly patients get fully well with antidepressant drugs," Morimoto said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Previously, Morimoto discovered that people who aren't helped by antidepressants also tend to have impairment of their executive functions. In fact, patients who suffer from executive dysfunction are about half as likely to respond to antidepressants.

In addition, executive dysfunction is common in geriatric depression. "About 40 percent of depressed seniors have impairment in executive functions," Morimoto said.

Morimoto and her colleagues reasoned that treating executive dysfunction could help people recover from depression. As such, the researchers wanted to develop a therapy to exercise and potentially improve people's executive functions. They used computer games, which prior research suggested may help strengthen mental functions such as memory.

The researchers developed one computer game that involved balls moving on a video screen; patients had to press a button when the balls changed color. This game helped test attention and accuracy. Another game involved rearranging multiple word lists into categories, which helped test speed and accuracy. Both games increased in difficulty over time based on how well people did.

The scientists tested the games on participants ages 60 to 89 who had major depression and failed to show improvement with antidepressant drugs, including escitalopram. The participants engaged in the computer activities for 30 hours over the course of four weeks.

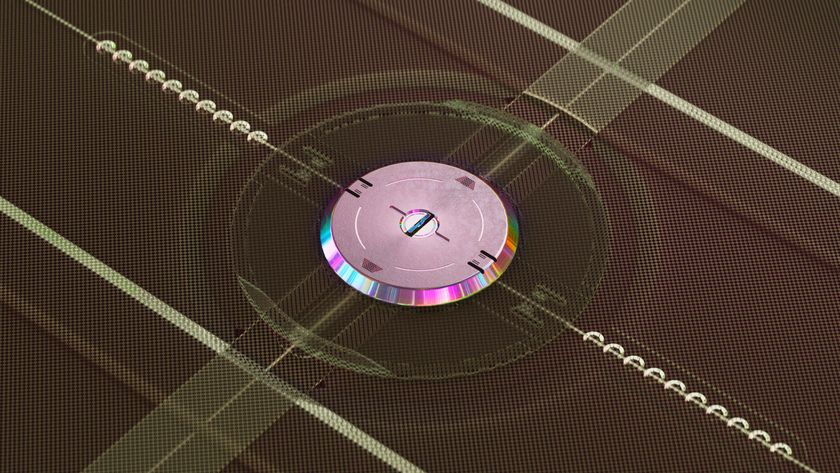

"Our findings suggest that the health and functioning of brain circuits responsible for executive functions are important for recovery from depression," Morimoto said.

The researchers noted this was a very small preliminary study, and they want to conduct a randomized controlled trial, Morimoto said.

This computer therapy could be used by itself or in conjunction with antidepressant drugs, Morimoto said. In addition, this computerized approach "can be extended to other mental disorders by reprogramming it to target the brain circuits found impaired in these disorders," Morimoto said. For instance, Morimoto said the researchers have started examining the effects of computerized therapy on patients who developed depression after suffering strokes.

The scientists detailed their findings online today (Aug. 5) in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Live Science and Space.com. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a master of arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a bachelor of arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica.