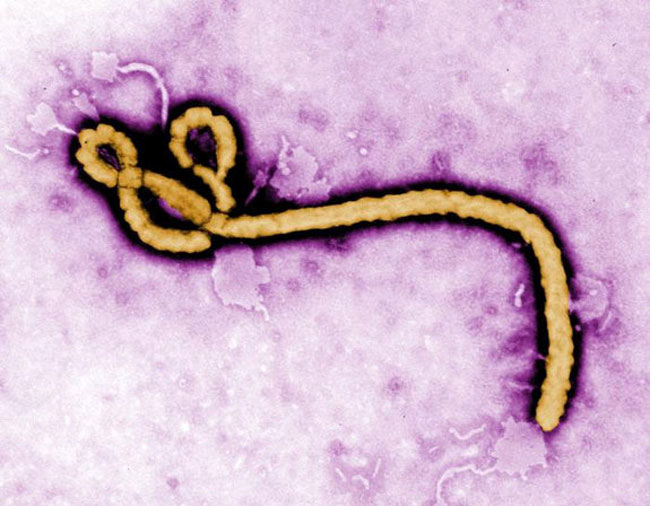

The Ebola outbreak is spreading within West Africa, with 158 deaths reported in the last week, according to the World Health Organization.

But despite what may seem like skyrocketing numbers, the disease is not that easy to spread in the absence of close contact with an infected person.

Ebola typically spreads through contact with bodily fluids, which include blood, vomit, feces, sweat, saliva, tears — and semen, said Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventive medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee.

That means it's theoretically possible to catch Ebola from sex, but that's probably not a common transmission route, Schaffner said.

"Of all the modes of transmission, that's going to be the last," Schaffner told Live Science. "It's a little like asking me, 'If we're all going to go from New York to San Francisco, will one of us walk?' That doesn't happen too often."

Ebola transmission

Unlike people with the flu or HIV, those who are infected with Ebola aren't contagious until they start showing symptoms. By that point, having sex would be the last thing on a patient's mind, Schaffner said. In another departure from other viral diseases, Ebola can't spread through airborne droplets from a sneeze or cough, Schaffner said. [10 Deadly Diseases That Hopped Across Species]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But although the broad outlines of how Ebola transmission works are clear, exactly how the virus behaves in borderline situations is less clear.

For instance, the virus can persist after death. The carcass of an ape that had Ebola remained infectious for three to four days after the animal died, according to a 2004 study in Science.

But it's not clear how likely it is that an object, such as a bed sheet or a chair smeared with blood or vomit from a sick person, could be a source of new infections in people, Schaffner said. The longer that virus particles remain outside of living cells, the less likely they are to remain infectious, Schaffner added. A 2007 study in the Journal of Infectious Diseases found that only two out of 33 objects taken from an Ebola ward in Uganda showed traces of active virus, and the contaminated objects were visibly bloody, according to the study.

And as for the chance that an object could spread the disease, someone would need to touch the soiled object, pick up a live virion, and then touch his or her eye or have virus particles sneak through an open cut in the skin or a mucous membrane, to actually get Ebola, he said.

Sex an unlikely route

The virus lurks in low numbers in the body during the first phases of infection. As a result, Ebola virus isn't present in bodily fluids until people feel sick — usually too sick to be intimate. But there have been too few cases of the disease for researchers to pinpoint the exact onset of contagiousness, Schaffner said.

If an infected person had sex at 1 o'clock in the afternoon, and then started showing symptoms at 6 p.m. that evening, could he or she have transmitted the disease?

"The answer is we don't know," Schaffner said.

A lab worker who contracted Ebola was still shedding the virus in his semen for 61 days after he recovered, according to the World Health Organization. And the Marburg virus, which is closely related to Ebola, shows up in semen 12 weeks after someone recovers, according to a 1971 study.

That suggests that Ebola could be sexually transmitted after recovery, Schaffner said.

Still, the sexual transmission route is unlikely, Schaffner said.

Human compassion can be deadly

Ebola's transmission dynamics make it a particularly brutal disease.

Many people die in isolation, after caring for and watching loved ones succumb to the illness, Dr. William Fischer II, an infectious disease specialist at the University of North Carolina, wrote in an email dispatch he sent home.

"Part of what makes Ebola so devastating in addition to the manner in which people die, is that this virus wipes out families. It penalizes those families who are close and transforms tradition into transmission," Fischer, who worked in Gueckedou, Guinea, during the current outbreak, wrote on June 4 this year.

In the part of West Africa where the outbreak is raging, it is considered a sign of love and respect to bathe the body of a loved one after death, Schaffner said. But that can be the time when the virus is near peak infectiousness, with viral loads sky-high in a person's corpse. Washing the body and even cleaning out bodily orifices, as some traditions require, only encourages the disease's spread, Schaffner said.

To try to combat this transmission mode, some health workers are suggesting cremating the bodies of loved ones, though that idea has not yet taken hold, Schaffner said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.