Photos of the World's Largest Asphalt Lake

Bubbling Oil

Hidden in the world's largest asphalt lake, scientists have discovered an array of metabolically active microbes living inside tiny water droplets sealed within oil. The microbes, the researchers found, are breaking down the oil into a range of metabolites. Here, a site at Pitch Lake where liquid oil bubbles up to the surface.

Sampling Oil

The researchers collected undisturbed oil samples from Pitch Lake in Le Brea (in Trinidad and Tobago). When they spread out the samples onto aluminum foil they could see small bubbles beneath the oil surface, many of which contained gas and so collapsed when punctured. Some of those bubbles, however, contained entrapped water droplets just 1 to 3 millimeters across. When they examined the droplets under a microscope they saw microbes, some that were actively moving.

Mining Oil

Their analyses of the samples from Pitch Lake (shown here) revealed the microbes that called the oil-encapsulated water droplets home were mostly members of the scientific orders Burkholderiales and Enterobacteriales. Other microbe groups found included: Bacteriodales, Rhodospirillales, Sphingomonadales and, at lower levels, Thermotogales and Nitrosomonadales, the researchers report in the Aug. 8, 2014 issue of the journal Science.

Here, a site at Pitch Lake where solidified oil is mined.

Solidified Oil

The microbial species found inside the Pitch Lake droplets seemed to be breaking down the oil into various organic molecules. "Each of these water droplets basically contains a little mini-ecosystem," study co-author Dirk Schulze-Makuch, an astrobiologist at Washington State University in Pullman, told Live Science. After looking at the chemistry of the droplets, Schulze-Makuch and colleagues think the water, rather than coming from rain, is ancient seawater or possibly brine from deep underground.

Shown here, solidified oil at a spot with mining activity on Pitch Lake.

Asphalt Abounds

The oil-munching microbes found in the study at Pitch Lake (shown here) suggest these "bugs" play a greater role than previously thought in breaking down oil, the researchers said. Even so, don't expect oil spills or oil deposits to, poof, vanish. The microbial process of degrading oil is very slow and happens on geologic time scales, the researchers said.

Transport Carriages

Pitch Lake, where the tiny droplet habitats were found, is about 250 feet (76 meters) deep at its center and holds about 10 million tons of pitch, according to UNESCO. The lake's asphalt is a mix of water, gas, bitumen and minerals (primarily silica sand with some fine clay), according to UNESCO. Here, transport carriages travel over the lake, located in Trinidad and Tobago.

Asphalt Lake

Though Pitch Lake is made of asphalt, apparently it still swishes. A natural slow stirring of the asphalt can be seen on the lake's surface, according to UNESCO. In fact, prehistoric trees and other old "debris" have been seen bubbling up to the lake's surface.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

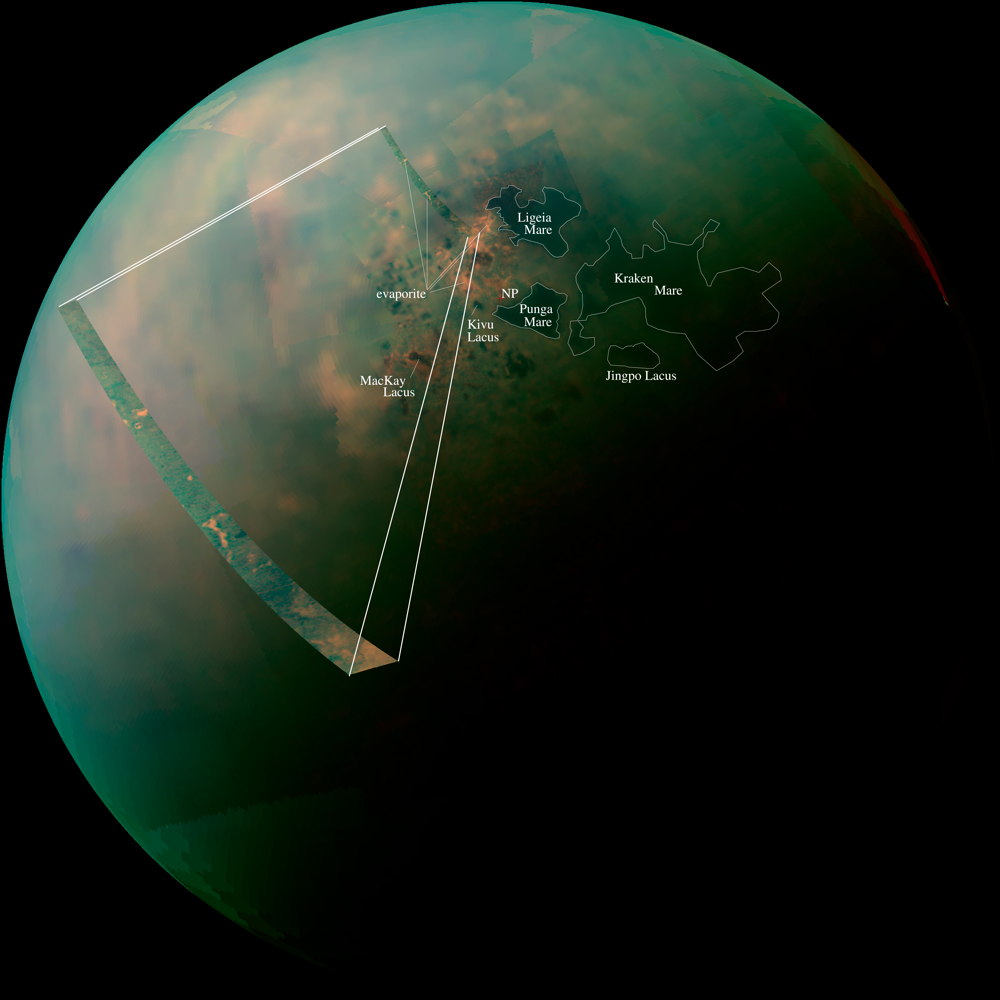

Titan Lakes

The asphalt lake finding has implications for the prospects of finding alien life elsewhere in the universe, particularly in the hydrocarbon lakes (shown here) on Saturn's largest moon Titan. Just as water droplets bubble up in Pitch Lake, water-ammonia mixtures may rise up to Titan's surface from below; and those mixtures may be capable of holding tiny life forms.

This false-color mosaic, released on Oct. 23, 2013, shows the differences in composition of surface materials around Titan's hydrocarbon lakes. The mosaic was created from infrared data collected by NASA's Cassini spacecraft.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.