Odds of El Niño Drop; Still Expected to Form

The El Niño that seems to be trying to form in the tropical Pacific Ocean is looking a little less likely now, though the chances of it developing are still double the normal odds, forecasters said in the latest monthly update on the cyclical climate phenomenon, released Thursday.

That update lowered the odds of an El Niño occurring in fall and early winter to 65 percent, down from 80 percent last month. But “we’re still fairly confident that El Niño will come,” said Michelle L’Heureux a meteorologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center, who puts out the El Niño forecasts along with the International Research Institute for Climate and Society at Columbia University.

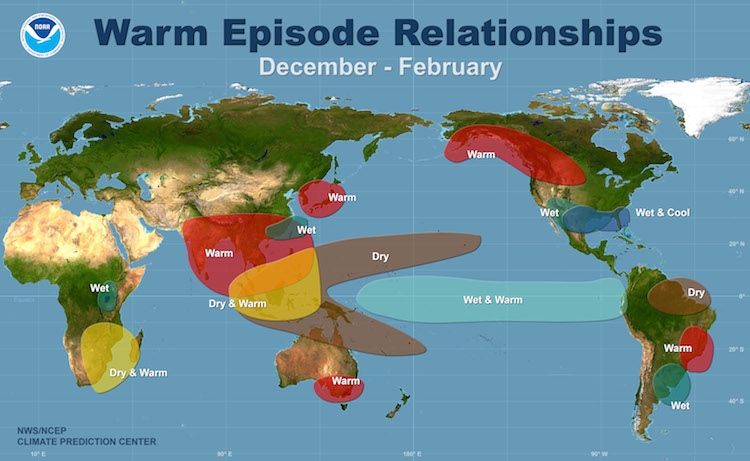

If and when the El Niño forms, it would influence weather and climate patterns in particular regions around the globe, for example, tamping down on hurricane activity in the Atlantic Ocean. Depending on its strength, it could also drive up global temperatures enough on top of the rise from human-induced warming to send 2015 into the record books.

How Will We Know When El Niño Finally Arrives? El Niño Expected to Limit 2014 Hurricane Season Why Do We Care So Much About El Niño?

While above-normal sea surface temperatures in the far eastern tropical Pacific — a hallmark of an El Niño event — have persisted, the warmth in other key surface regions and below the surface has ebbed. The shifts in atmospheric patterns that accompany an El Niño also have yet to materialize. These factors combined caused forecasters to lower the odds.

The updated probabilities mean that instead of a 4-in-5 chance that an El Niño would materialize, there is now a 2-in-3 chance it would, L’Heureux said.

But even a 65 percent chance is double the typical odds of seeing an El Niño in winter, she said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Forecasters think any El Niño that does develop will be a weak to moderate in strength, though a strong event can’t be completely ruled out. But going from such a current weak showing to a strong El Niño “would certainly be unprecedented,” L’Heureux told Climate Central.

El Niño is the warm phase of a larger cycle called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, which includes its counterpart La Niña. Normally, the western tropical Pacific is warmer than the east, but during an El Niño, this pattern reverses. The trade winds that normally blow from east to west weaken or even reverse.

L’Heureux and other forecasters have been watching the development of this potential El Niño since issuing an El Niño Watch in March. In April, the situation looked ripe for an El Niño to form this summer, as a huge plume of warm water, called a Kelvin wave, slid through the ocean and brought exceptionally warm waters to the eastern Pacific. The development drew comparisons to the strong El Niño of 1997-1998.

But while the ocean looked set for the El Niño, the atmosphere wasn’t playing along, and storm activity developing over Indonesia, which normally dries during an El Niño.

Over the past month, the pool of warm water below the ocean’s surface (and at an area of the ocean surface called the Niño 3.4 region) has dissipated, prompting L’Heureux and her colleagues to say ENSO is still in its neutral phase.

The cool-down in the Niño 3.4 region was actually anticipated by the ENSO forecast models, and is consistent with the upwelling phase of the Kelvin wave, when some of the excess heat dissipates. The fact that they caught that slight dip gives L’Heureux and her colleagues more confidence that the models are on target in their continued projections that an El Niño will actually develop.

“To me, that enhances their credibility,” L’Heureux said.

And while she is loathe to compare any one El Niño to another since the record of well-observed El Niños is short, L’Heureux said that other El Niños saw similar dips in sea surface temperatures around this time in the season before finally forming. Of the seven El Niños that have formed since 1990 (as far back as weekly sea surface temperature records go), three — 1994, 2004 and 2006 — saw similar drops, all of which happened in late June and July.

“So there is precedent for this, I guess, sort of summertime lull,” L’Heureux said. And summer is actually a tricky time to get the atmosphere and ocean to act in sync, she added, so it could simply be seasonal effects keeping the El Niño from moving forward.

While forecasters are still betting an El Niño will happen, L’Heureux did say she keeps looking back at the data from 2012, when what forecasters thought would be an El Niño completely fizzled. They called off that watch when the sea surface temperatures were near average across the whole tropical Pacific and the models were “starting to tank,” she said. “And we really haven’t reached that point” with this event, she added.

The models suggest that some of the lost heat will come back, but if the atmosphere doesn’t start playing along and the heat doesn’t regenerate, “the models will catch on,” L’Heureux said.

You May Also Like See Power Plants Most Vulnerable to Flooding Indigenous Groups Give Tropical Forests a Carbon Boost Toledo’s Algae Bloom in Line with Climate Projections Has Your City Reached its Peak Heat Yet?

Follow the author on Twitter @AndreaTWeather or @ClimateCentral. We're also on Facebook & other social networks. Original article on Climate Central.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.