Dark Lightning Images: NASA's Fermi Telescope Captures Powerful Gamma-Ray Flashes

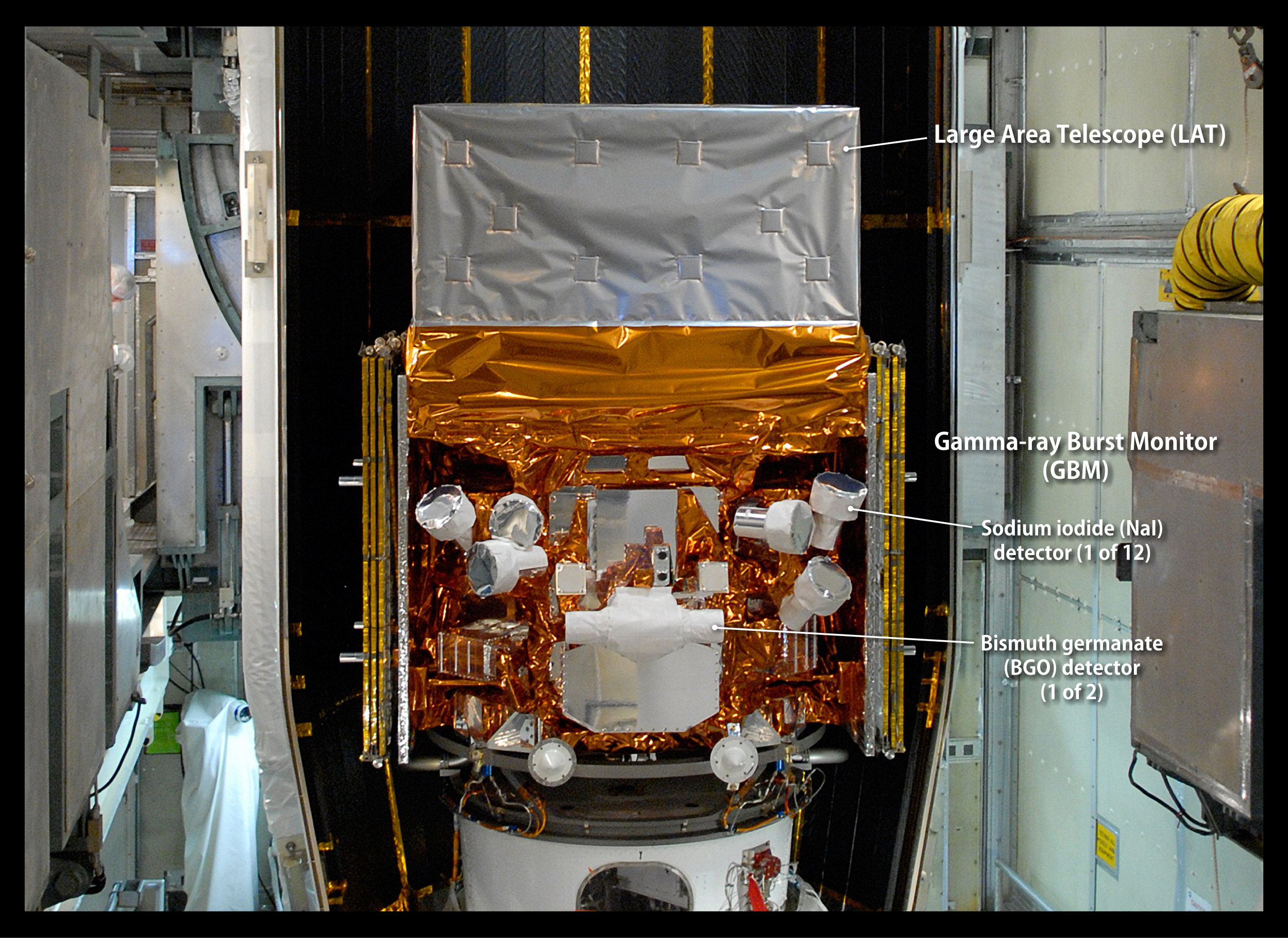

Fermi Telescope

Gamma rays are the brightest, most powerful, explosions in the universe, often emitted from supernova or supermassive black holes. But these giant flashes can also have Earthly origins, stemming from intense storms — these are called terrestrial gamma-ray flashes. NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope (shown here in a May 2008 image), which launched in June 2008, can detect both types of gamma rays. The telescope can see the terrestrial type up to a distance of about 500 miles (800 kilometers).

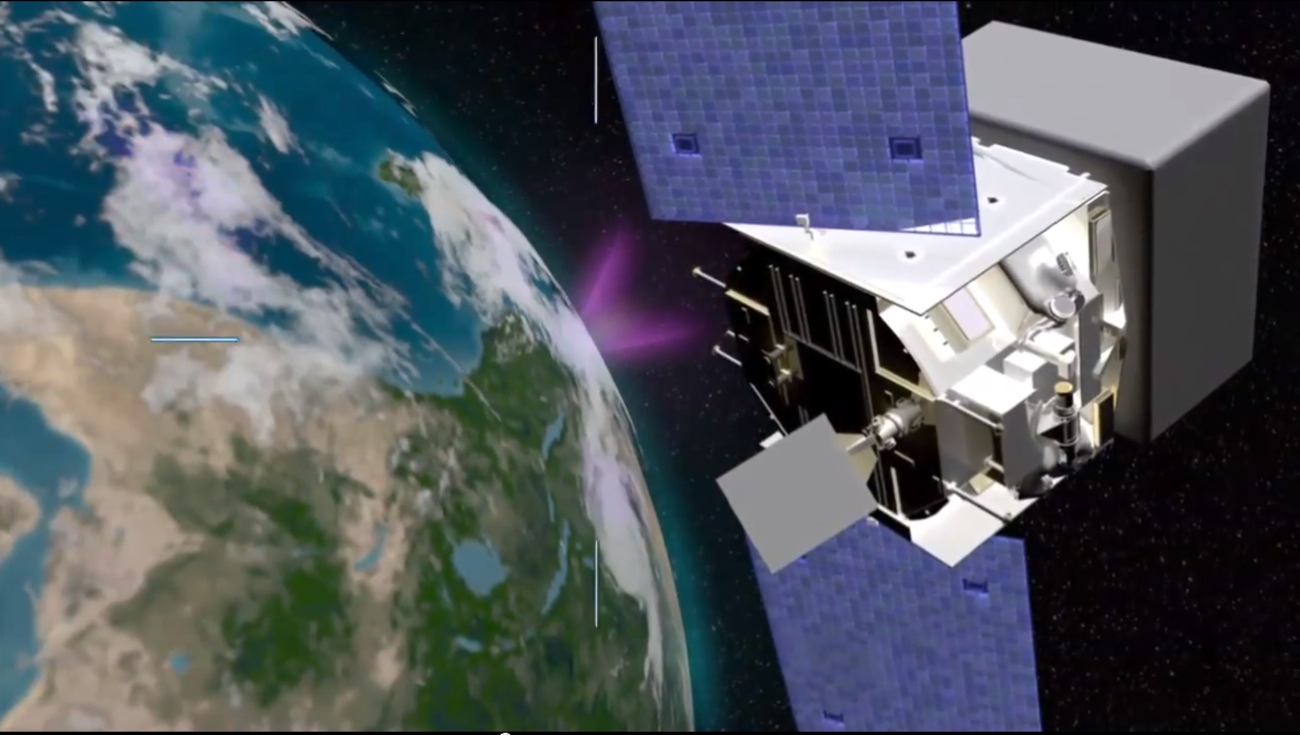

Egypt Flash

On Dec. 14 2009 as Fermi passed over Egypt it spotted a TGF from a thunderstom in Zambia. The TGF flashed over spacecraft's horizon where Fermi couldn't actually "see it."

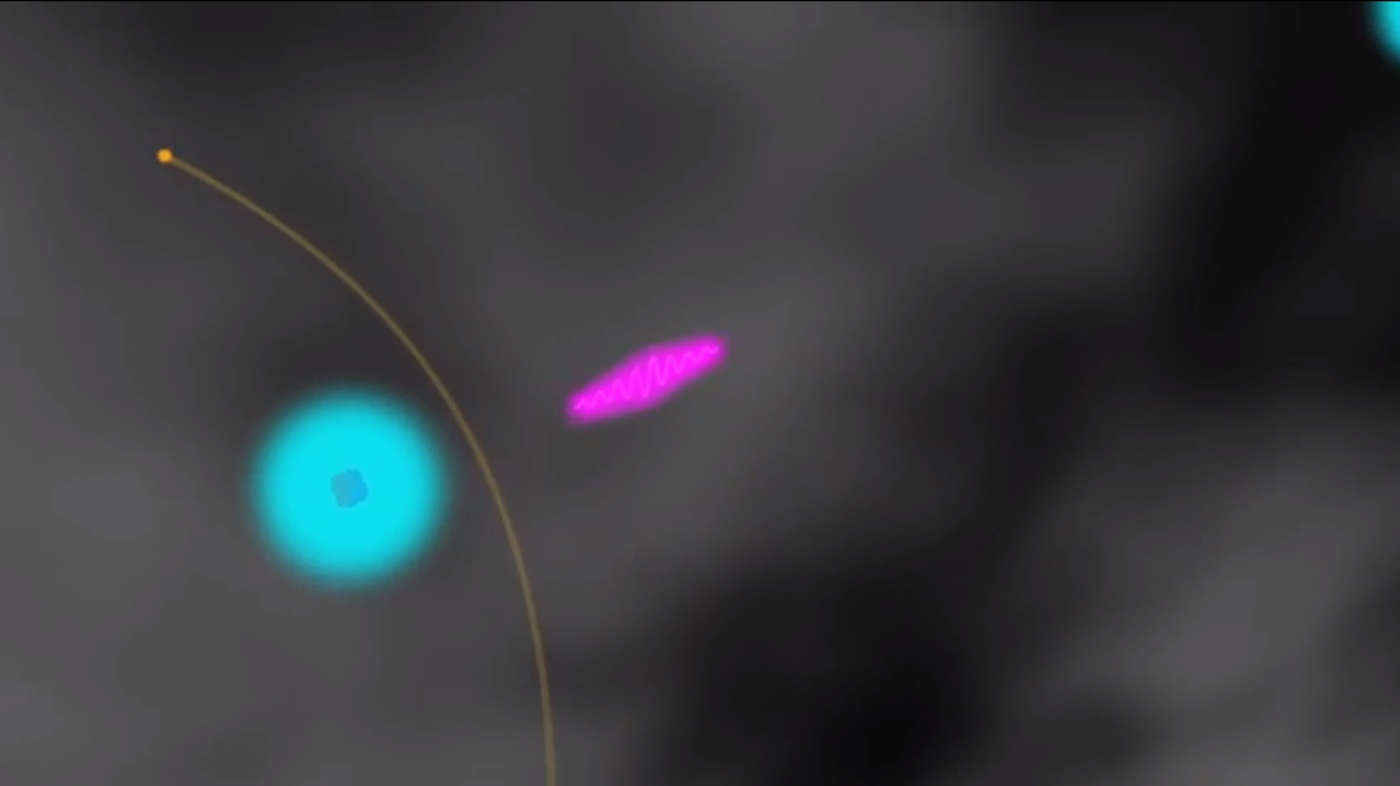

Terrestrial Gamma Rays

The TGFs are thought to begin in the intense electrical fields of thunderstorms. Within this field, the electrons get accelerated above the storm where the air is thin, ramping up to near light-speed. Here, an artist interpretation of electrons accelerating upward from a thunderhead.

Making Gamma Rays

When these electrons encounter an atom, they emit gamma rays, shown here in this artist impression of the powerful process.

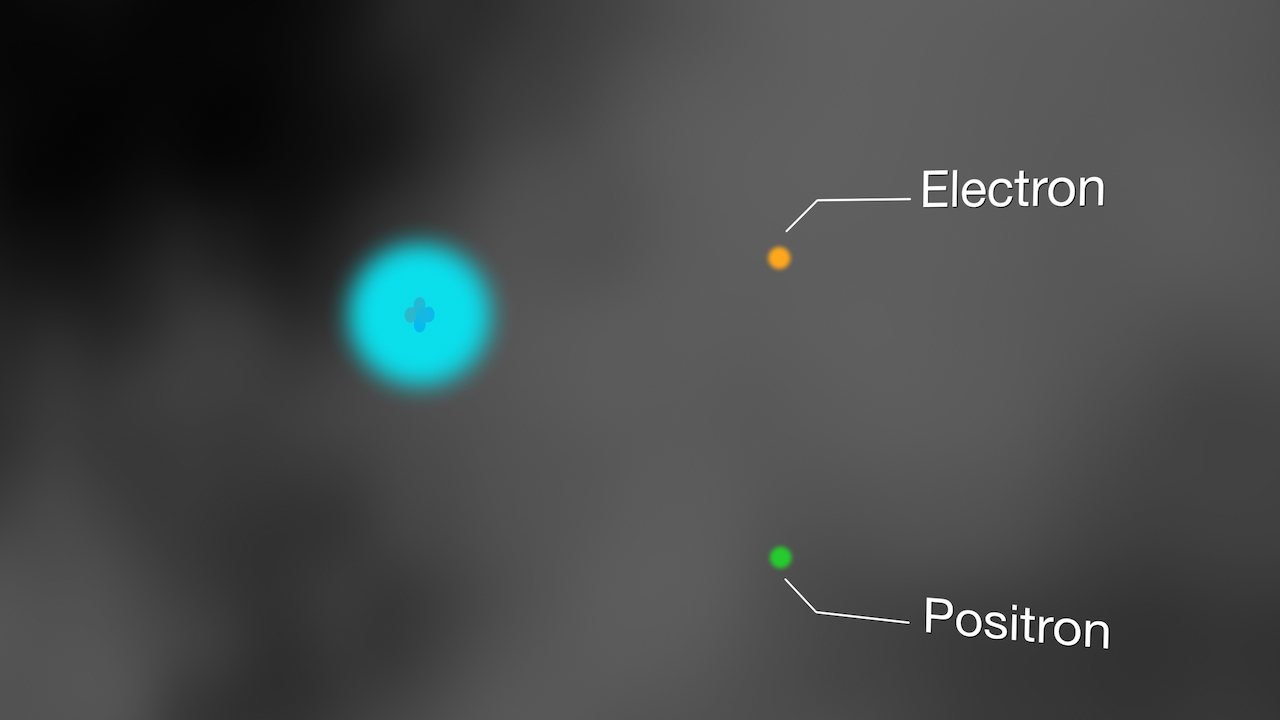

Particle Pair

Very rarely one of these gamma rays, traveling at near light-speed, will graze an atom, passing through its electron shell, and transform into a pair of particles — a normal matter electron and an antimatter electron, called a positron.

Along Magnetic Field Lines

So how did Fermi detect this gamma-ray flash above Zambia? Turns out, the gamma rays travel in straight lines, but the charged particles spiral along Earth's magnetic field lines, according to a NASA video.

Hitting Fermi

As those high-energy particles spiraled upward, they hit the Fermi Gamma-Ray Space Telescope. The high-energy particles rode upward on magnetic field lines and then struck the spacecraft.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fermi turns pink

The postirons annihilated when they struck electrons on the Fermi telescope, creating a flash of gamma rays, and, for an instant, the Fermi craft became a source of gamma rays, setting off its own detectors.

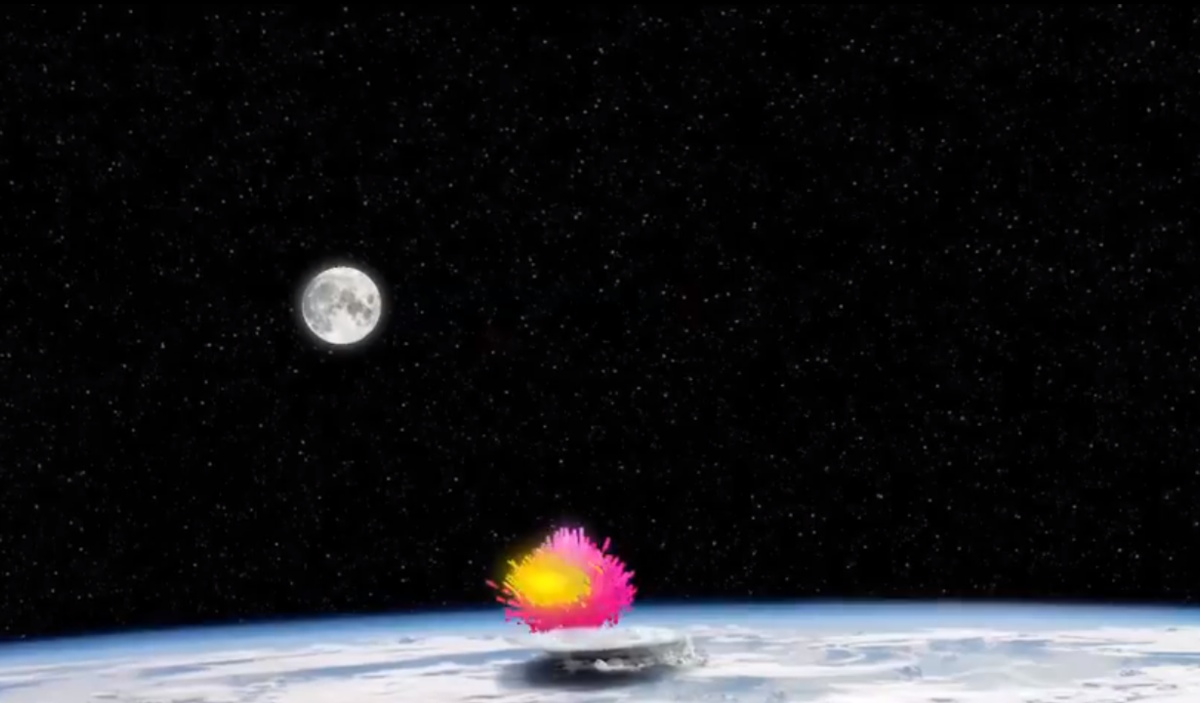

Flash Start

An illustration showing the launch of a gamma-ray flash from an intense storm on Earth, with (magenta) and high-energy electrons (yellow) shooting upward.

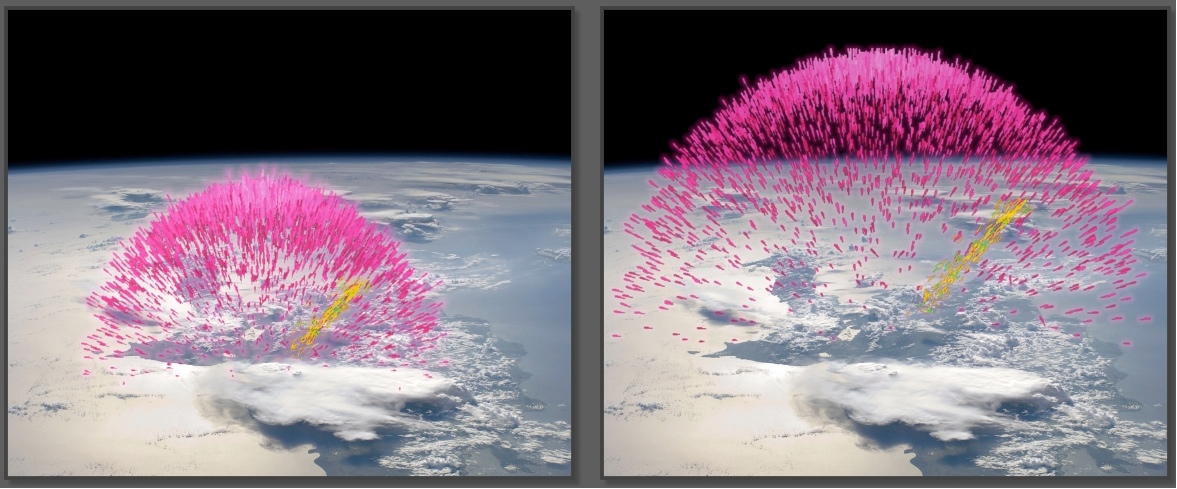

High-Energy Electrons

Here a terrestrial gamma-ray flash just 1.98 seconds old (right panel), revealing its electron/positron beam, moving from just 9.3 miles (15 kilometers) altitude to some 373 miles (600 km), where it may intercept such spacecraft as NASA's Fermi Gama-Ray Space Telescope. (Gamma rays are shown in magenta and high-energy electrons in yellow.)

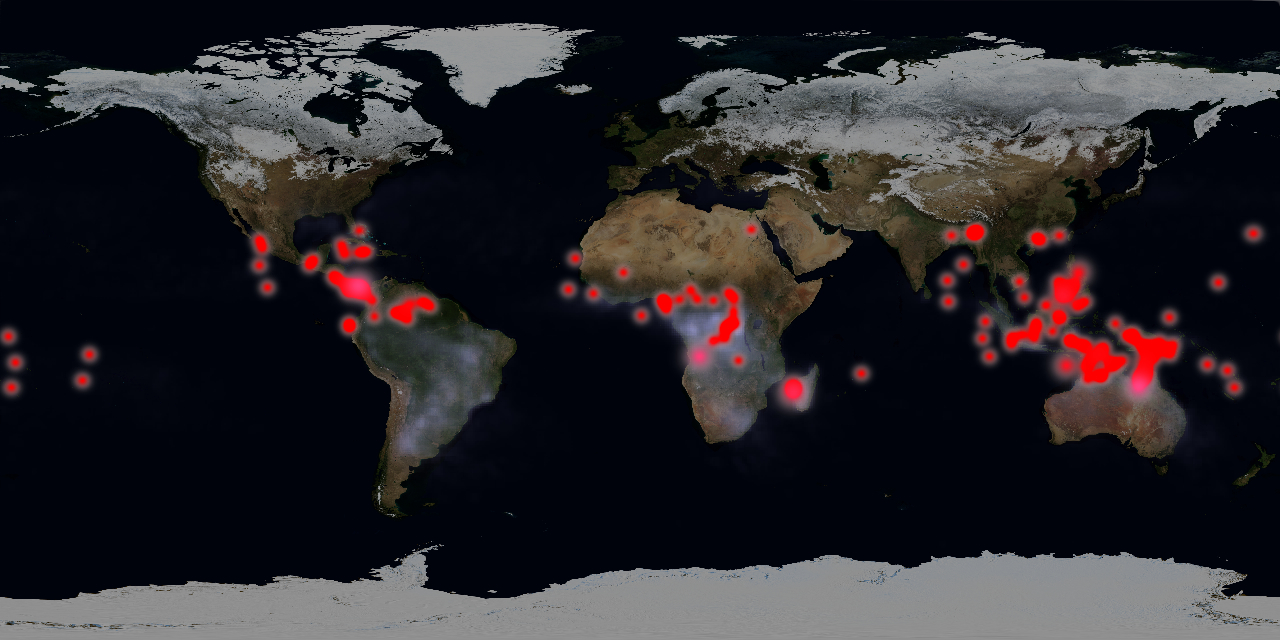

Lots of Flashes

Researchers estimate there may be as many as 500 terrestrial gamma-ray flashes each day, according to a NASA video on the phenomenon.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.