Forget about the man in the moon, there's a new ghostly face in space — this time on a comet.

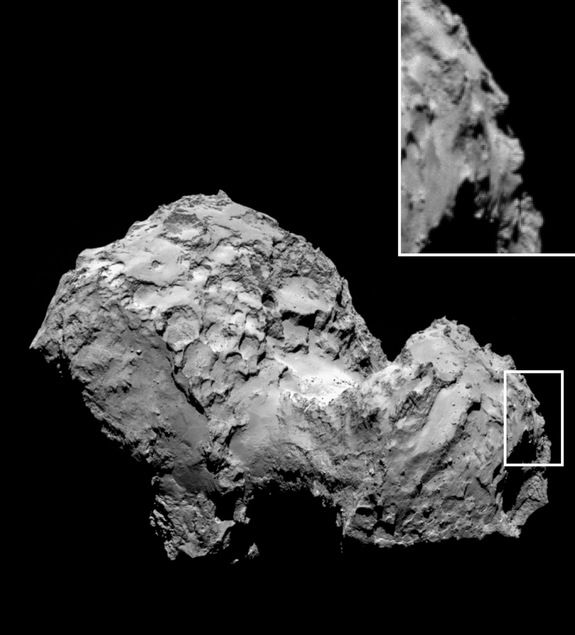

As the European spacecraft Rosetta approached the comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko on Aug. 3, it snapped a photo of the comet's rocky surface — and what looked like a face on the right side of the 2.5-mile-wide (4 kilometers) space rock.

Though the face on the comet, with its shadowy profile, looks almost sinister, it is far from unique: Humans are wired to see faces everywhere.

In fact, the phenomenon is so common that it even has a name: Pareidolia, which in Greek means, in essence, "faulty image."

"Your brain is constantly trying to make the most out of just the tiniest thing," said David Huber, a psychologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, who has studied the phenomenon. "You're sort of in overdrive on imagining from limited information that there is a face."

Faces, faces everywhere

From the Shroud of Turin, thought to carry the imprint of the crucified Jesus' face and body, to faces in the clouds and the Virgin Mary on a grilled cheese sandwich, people have always seen faces in everyday objects. Even the faintest hint of eyes, nose and a mouth in roughly the right places will often trigger the brain's facial recognition system, Huber said. [Face on a Comet: See Images of Faces in Space ]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In several studies, Huber and his colleagues showed people a screen with random noise — essentially TV static — and then asked them to report when they saw faces. Not surprisingly, people frequently saw faces in the pixelated noise. The key was that there needed to be spots of contrast, such as dark spots in a lighter area, positioned a certain way.

"What you're looking for is literally that canonical eyes, nose and mouth: kind of a smiley face," Huber told Live Science.

In addition, these features need a frame for people to interpret them as a face, likely because people tend to imagine faces as part of a head, Huber said.

"That's why if you see a face in toast, it's important that you have the rim of the toast," Huber said.

Brain processing

When people see faces in images, a brain area called the fusiform face region lights up in brain scans, said Kang Lee, a developmental neuroscientist at the University of Toronto, in Canada, who has worked with Huber on several studies of how people process faces. [Seeing Things On Mars: A History of Martian Illusions]

This brain region is likely a key junction point where low-level visual information is processed to say "Aha! It's a face," Huber said.

The distance between facial features seems to play a key role in the brain's ability to spot and uniquely identify different faces.

For instance, some people are much better at facial recognition. It turns out those people also excel at matching an adult face with the person's baby photo. These face experts are probably focusing their attention on details such as the distance between the eyes, nose and mouth, which stay roughly constant as a person grows, Huber said.

Interestingly, a different brain region, called the inferior frontal gyrus, is involved with recognizing race and gender in faces, and categorizing faces as familiar or unfamiliar, Lee said.

Some people seem to be more prone to pareidolia as well. Religious people and those who believe in the paranormal are more likely to see faces and emotional expressions in "face-like artifacts," according to a 2012 study published in the journal Applied Cognitive Psychology.

The front part of the brain, which manages the expectation for seeing faces, sends signals backward to the visual processing regions such as the fusiform face region, so if this backward signaling is too strong, people could be "too primed to see faces," Lee told Live Science.

Evolutionary tool

It makes sense that humans, even more than other animals, see faces everywhere, said Lee (whose favorite object-with-a-face is a "very cute" parking meter.)

"Faces are so important to our social interactions," Lee said.

Cueing in to faces allows young babies to focus on the mouth to learn language or see key social signals. Learning to quickly spot faces could also help identify threatening people, which provides an evolutionary advantage by helping people avoid danger. Alternatively, the risks involved with seeing faces everywhere are fairly benign, such as being spooked by a "ghost" in the dusk, Huber said.

Unlike chimpanzees and other animals, the dark and white parts of the eye are clearly visible in humans, which makes it easier to see which way someone is looking. Humans also have much less facial hair than great apes, making it much easier to see the two eyes, one nose and a mouth configuration of the human face, Lee said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.