How Despots Arose With Agriculture (Op-Ed)

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

For hundreds of thousands of years humans lived in hunter-gatherer societies, eating wild plants and animals. Inequality in these groups is thought to have been very low, with evidence suggesting food and other resources were shared equally between all individuals. In fact, in the hunter-gatherer societies that still exist today we see that all individuals have a say in group decision making. Although some individuals may act as leaders in the sense of guiding discussions, they cannot force others to follow them.

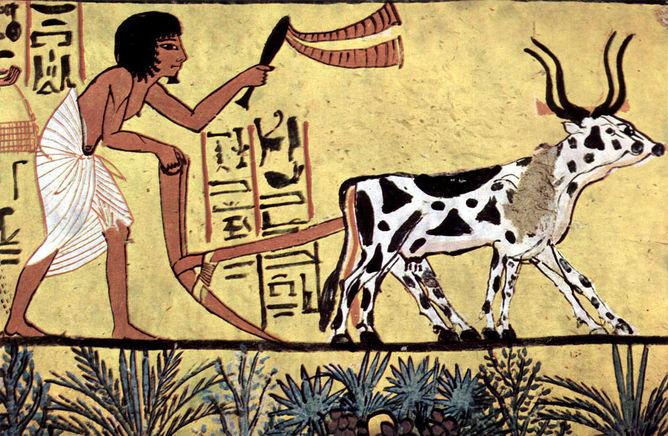

But it seems that with the beginning of agriculture around 10,000 years ago, this changed. An elite class began to monopolise resources and were able to command the labour of others to do things, such as build monuments in their honour. So how was it that egalitarian societies, where all men were equal, transitioned into hierarchical societies where despots reigned?

In recent years archaeologists have tended to focus on the means by which would-be leaders could coerce other individuals into following them (so-called theories of agency). But while leaders probably did coerce their followers once they were in power, it is difficult to see how they could do so at the outset. After all, if all individuals started out with equal resources and equal status, how could one individual force 30 others to do their bidding? This problem forces us to examine the benefits that would-be leaders could provide to their followers – and this is where agriculture comes in.

While hunting wild game did not involve much co-ordination beyond placing traps and positioning hunters, agriculture presented an opportunity to massively increase the amount of food that could be produced. A classic example is the development of irrigation systems, which allowed crops to be grown further away from rivers and water sources. Although the role of irrigation systems in creating despotic states has been overstated in the past, they certainly would have created an opportunity for would-be leaders to behave entrepreneurially by managing their construction. Those that chose to follow their agricultural-technologist leader would then benefit from access to irrigation. This would provide the benefit of increased food production, enhancing both their quality of life and the number of surviving offspring they could produce.

In this way, social hierarchy could initially arise voluntarily – because individuals that chose to follow the leader were materially better off than those that did not. But under what conditions does this voluntary leadership, where everybody benefits, turn into despotism? I tried to answer this question with a new computational model, which has highlighted two key linked factors.

The first is population growth. When populations are small it’s relatively easy for individuals to go back to a leaderless way of life, for example by moving to a new patch of land. This seems to happen in modern hunter-gatherer groups, where people may simply walk away from a bullying leader in the middle of the night. But as population density increases, it becomes harder and harder to find free land to move to that is not controlled by the leader and their followers. Model simulations demonstrate that positive feedback between leaders increasing resource production and population growth can create an obligatory hierarchy, destroying the viability of leaderless life in the area. And empirically, hierarchy formation most often co-occurs with an increase in food production that drives population growth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The second factor is the cost of changing the leader. Even if individuals are locked into a hierarchy, despotism is not inevitable if individuals can readily choose to follow a different leader. For example, by moving to a different group with a different leader. Group membership in hunter-gatherer societies is quite fluid, so this is relatively easy. But with agriculture, individuals would have become tied to a plot of land in which they had invested, making leaving the group very costly. This would become even more extreme with irrigation farming, where farmers would be tied to the system. Indeed, the most despotic early states arose in locations such as Egypt, where agriculture had to happen in a narrow valley along the Nile, making dispersal very difficult.

So the use of agriculture established human societies and provided for them in some ways that improved over hunter-gathering. But it shattered the social norm and facilitated the rise of despotism by attracting followers to entrepreneurial leaders that could provide them with benefits, by increasing population density which reduced the ability for others to survive outside the hierarchical group and by making it so costly to leave the group that to do so was unattractive even when faced with despotic leaders. Even in ancient times at the dawn of agriculture there was, it seems, no such thing as a free lunch.

Simon Powers receives funding from Swiss NSF grant PP00P3-123344.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article. Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.