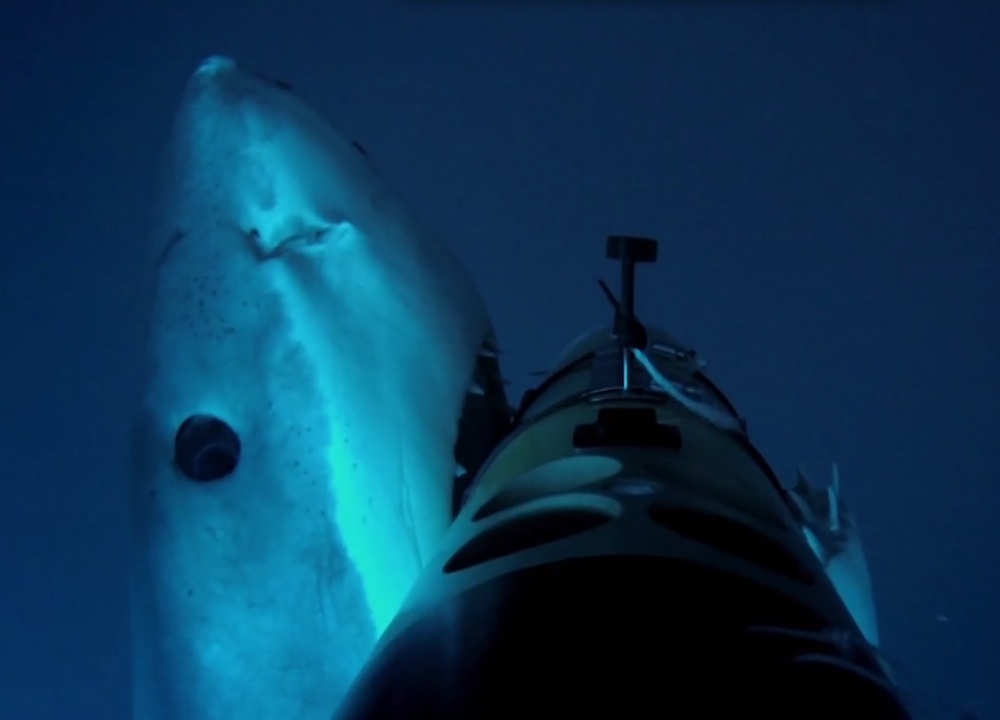

A silhouette hovers in the water as a great white shark circles in the inky darkness below. Suddenly, the shark surges upward, jaws open, and takes a bite.

The shark attack on an underwater robot was captured in footage from the autonomous vehicle REMUS SharkCam. The shark probably attacked because it mistook the vehicle for a seal or other tasty animal, said Amy Kukulya, an engineer at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Massachusetts who helped design the robot.

The attack occurred during the vehicle's recent expedition to Guadalupe Island in Mexico to track great white sharks as they search for prey. Viewers can see the shark attack on the Discovery Channel's "Jaws Strikes Back," which airs Monday, Aug. 11 at 9 p.m. ET. [See the Great White Attack the Robot (Video)]

Ocean hunters

Great white sharks are some of the most feared species in the ocean. The apex predators live in nearly all the world's oceans and undertake the longest known migration of any fish. Though the movie "Jaws" gave the sharks a terrifying reputation, the giant sharks kill just a handful of people each year. In fact, sharks are more likely to be prey for humans, who prize their fins for shark fin soup or hunt the creatures for sport. The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists the great white shark as vulnerable, meaning the species faces a high risk of extinction in the wild.

Scientists have scrutinized almost every part of the great white shark's anatomy and life cycle, from the shark's ability to sense electric-field disruptions by prey and predators, to its diet, to its life span (up to 60 years). Researchers have even found that some other shark species, such as sand tiger sharks, gobble up each other in utero. [Image Gallery: Great White Sharks]

But most of what scientists knew about great whites' hunting habits was based on dead animals that had washed ashore, or seals with chunks of their tails bitten off.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To get a real-time picture of great whites' hunting habits and migratory patterns, Kukulya and her colleagues developed the REMUS SharkCam. The remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV), which is a cylindrical shape about 6 feet (1.8 meters) long and 7.5 inches (19 centimeters) in diameter, carries a raft of sensors, including sensors that ping a tag on a shark, and determine the shark's location when the tag respondsto that ping.

"It's playing this advanced Marco Polo game, if you will," Kukulya told Live Science.

The robot then uses a sophisticated computer program to set its own trajectory in relation to the shark, completing "flybys" and sometimes tailing the big animals. Onboard cameras can then provide an unprecedented view of the sea beasts, Kukulya said. The goal is to get close — but not so close that the ROV disrupts the shark's natural behavior, she added.

Different hunting strategies

The terrifying attack on the SharkCam reveals firsthand the flexibility of the great white's hunting strategy. So far, the team has tracked about 10 different sharks in Cape Cod and Mexico, and the sharks seem to hunt differently in each locale.

In Cape Cod, the water is murky and shallow. Scuba divers rarely frequent the waters. In the crystal-clear waters off Guadalupe Island in Mexico, however, the great white sharks hunt seal colonies in water with 100-foot (30 m) visibility. The island is near the continental shelf, with the ocean floor thousands of feet below. Scuba divers often descend into the water in shark cages.

Sharks around Guadalupe Island stalk prey from the deep, nearly 450 feet (137 m) below the surface. Once they spotted their mark, they swiftly rose vertically through the water column to attack, the ROV revealed.

The hunters probably lurked at the edge of darkness so they could look up and see their prey while remaining hidden themselves.

"It proves that they're silhouetting their prey and making these deep-water attacks," Kukulya said.

The Cape Cod sharks didn't hunt from below, probably because the waters are too shallow and murky, Kukulya said.

Follow Tia Ghose on Twitter and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.