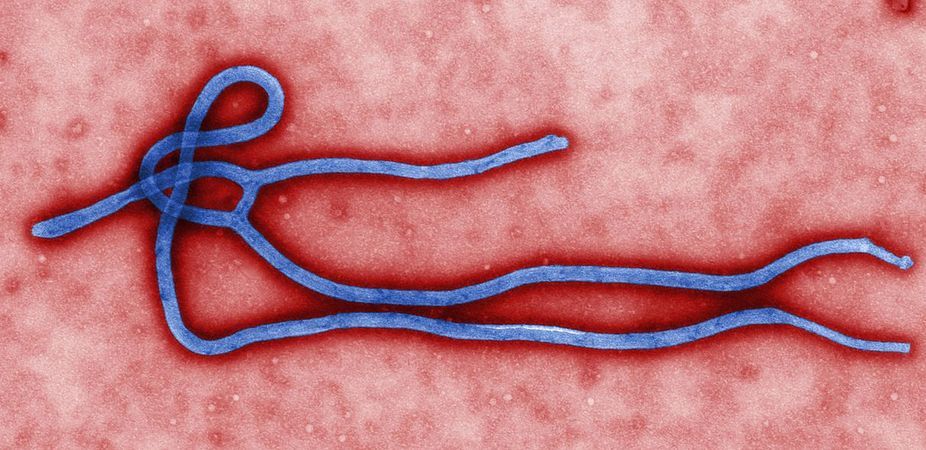

Should Controversial Ebola Treatment Be Given to More Patients?

Giving experimental treatments to patients infected with Ebola in West Africa is, indeed, the ethical thing to do, even though the risks and benefits of these treatments are unknown, a panel of experts has decided.

The panel, convened by the World Health Organization, assembled on Monday (Aug. 11) to discuss the ethics of using experimental treatments in the Ebola outbreak, which has killed at least 1,013 of the more than 1,800 people infected to date in Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia.

"In the particular circumstances of this outbreak, and provided certain conditions are met, the panel reached consensus that it is ethical to offer unproven interventions with as-yet-unknown efficacy and adverse effects, as potential treatment or prevention," WHO said in a statement today (Aug. 12).

One factor that prompted the WHO panel to meet was the news that two American health care workers and one Spanish priest had received an experimental Ebola drug called ZMapp, which had previously been tested only in animals, and is in limited supply. The priest died from Ebola today, according to news reports.

Experts stressed that, despite reports that the two American patients are doing well, this does not mean that the drug was helpful, nor does it indicate its possible harms.

The fact that two patients given the treatment have not died from Ebola "doesn’t mean it's effective, and doesn't meant its safe," said Dr. Kevin Donovan, of Georgetown University Medical Center.

The drug was given because "Ebola virus is a scary, deadly disease," Donovan said. "But if we continue in this uncontrolled way, we won't know if the therapies are safe or effective," Donovan said. For this, clinical trials need to be conducted, he said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In general, before experimental treatments are used, certain ethical criteria must be met. For instance, health care workers must make it clear to patients that the treatments are unproven and may carry certain risks, and patients must provide informed consent, WHO said.

However, experts cautioned that experimental treatments need at least some safety testing before they are used in people, because treatments could be very harmful to patients, and not everyone with Ebola will die from the disease. [How Do People Survive Ebola?]

"When you see public health emergencies… our first humanitarian response is to think, 'Well, if somebody's dying, and it's hopeless and they consent, why would we not want to give them every possible hope'" by using an experimental drug? said Lawrence Gostin, director of the O'Neill Institute for National and Global Health Law at Georgetown University. On the other hand, there are regulatory agencies that are tasked with making sure medical treatments do not harm people, Gostin said.

"I do think there has to be at least minimal safety testing before we administer experimental drugs to any patients," Gostin said today at a news conference organized by Georgetown University. "The death rate [from Ebola in the current outbreak] is about 55 percent, and some drugs can be extremely toxic."

Gostin said he did not know what the threshold for safety testing should be, but that experts should decide on one.

WHO said that, whenever an experimental treatment is used, "there is a moral obligation to collect and share all data generated," to better understand the safety and efficacy of the drugs.

Dr. Jesse Goodman, also of Georgetown University Medical Center, said that it is possible to conduct controlled trials in the current outbreak.

"For one of the first times, we are in a position where they could be done," Goodman said. "We have promising [drug] candidates; this is an important opportunity" to be able to find out what works to treat the disease, he said.

Follow Rachael Rettner @RachaelRettner. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Rachael is a Live Science contributor, and was a former channel editor and senior writer for Live Science between 2010 and 2022. She has a master's degree in journalism from New York University's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. She also holds a B.S. in molecular biology and an M.S. in biology from the University of California, San Diego. Her work has appeared in Scienceline, The Washington Post and Scientific American.