Butterfly-headed reptile

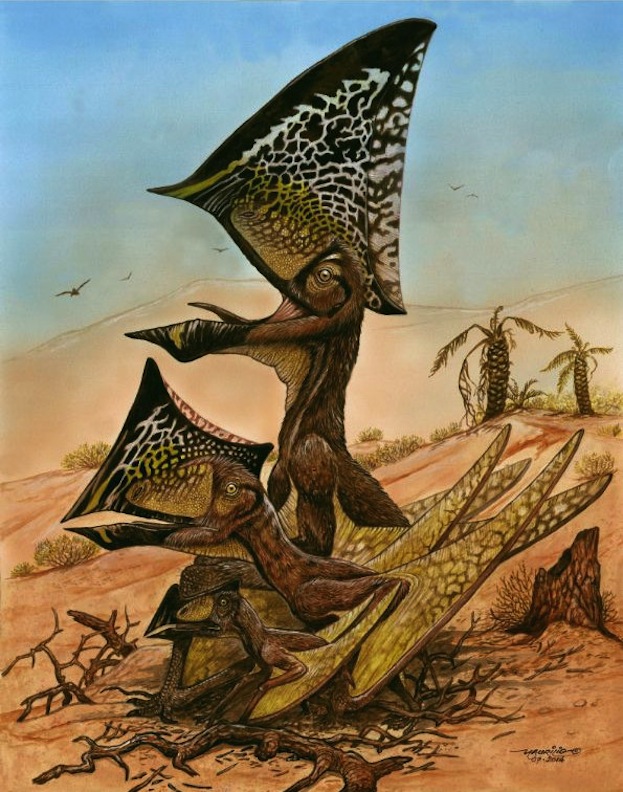

Researchers in Brazil have unearthed a new species of flying reptile, Caiuajara dobruskii from the Cretaceous Period.

Bony crest

The odd-looking creature, described in a 2014 PLOS ONE paper, sported a bony crest on its head that looked like butterfly wings. The crests changed in size an orientation as juveniles (white) grew into adulthood (red).

Huge trove

The species was identified from a bone bed about 213 square feet (20 square meters) in area, which contained fragments from potentially hundreds of individuals. The aggregation suggests pterosaurs were social animals that flocked together.

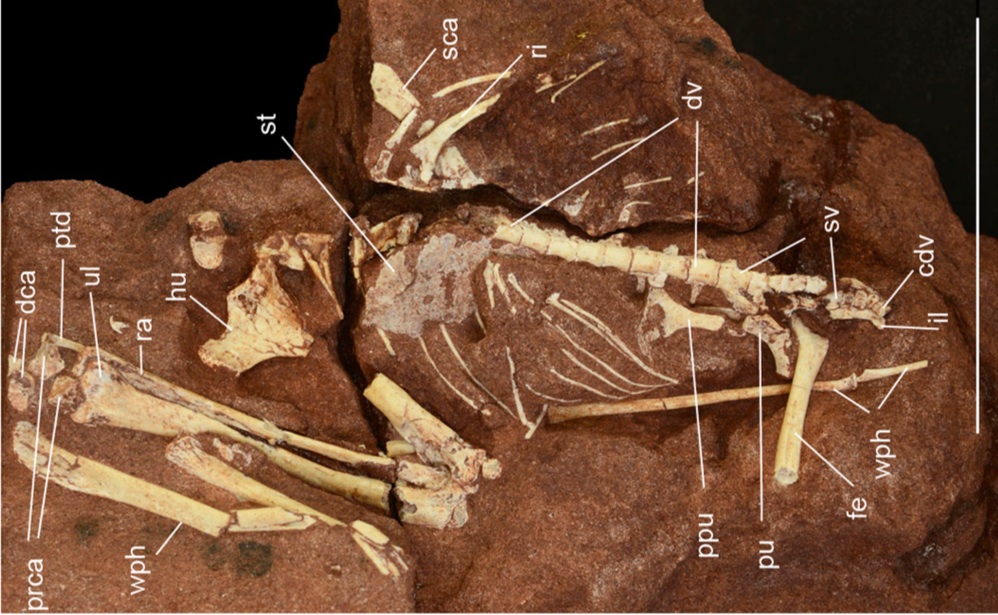

Leg bones

Several leg bones from animals of various sizes were unearthed. Bones from below the head didn't change that much in size as the animals grew, suggesting they could have flown at a very young age.

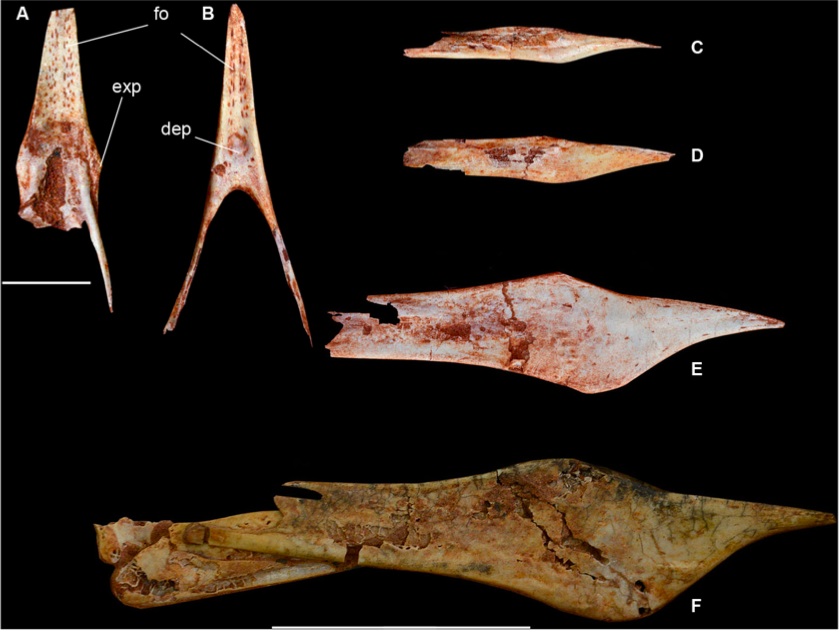

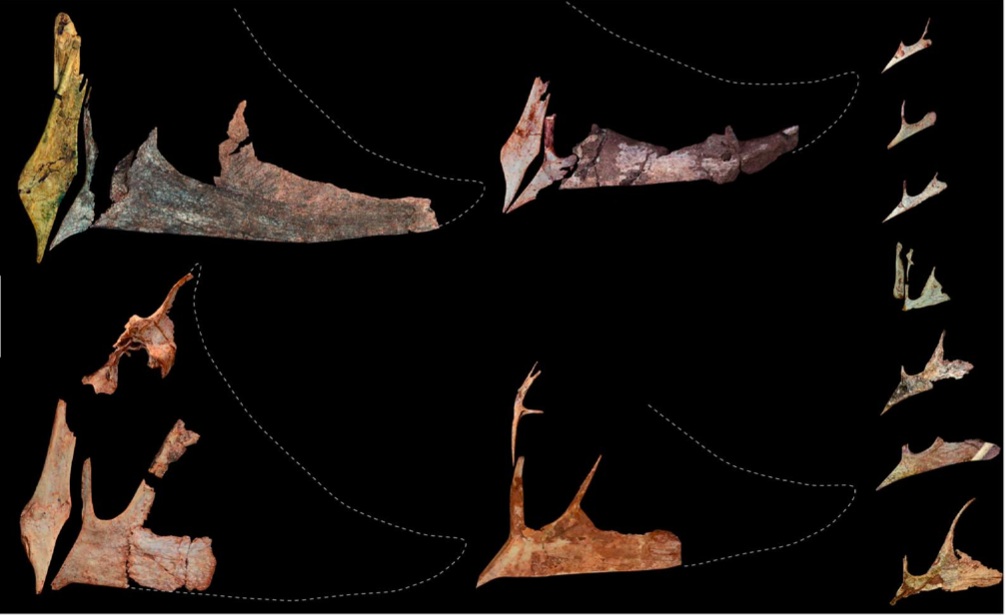

Jaw bones

The lower jaw bones from juveniles, adolescents and adults were unearthed.

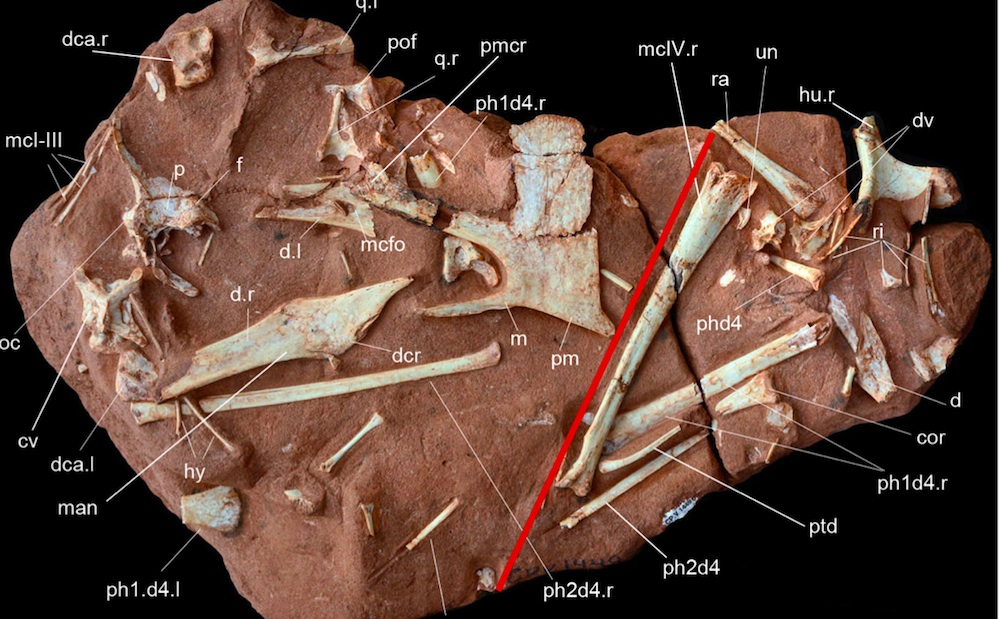

Partially intact

Some of the ancient reptile skeletons were partially intact and had their 3D structure preserved.

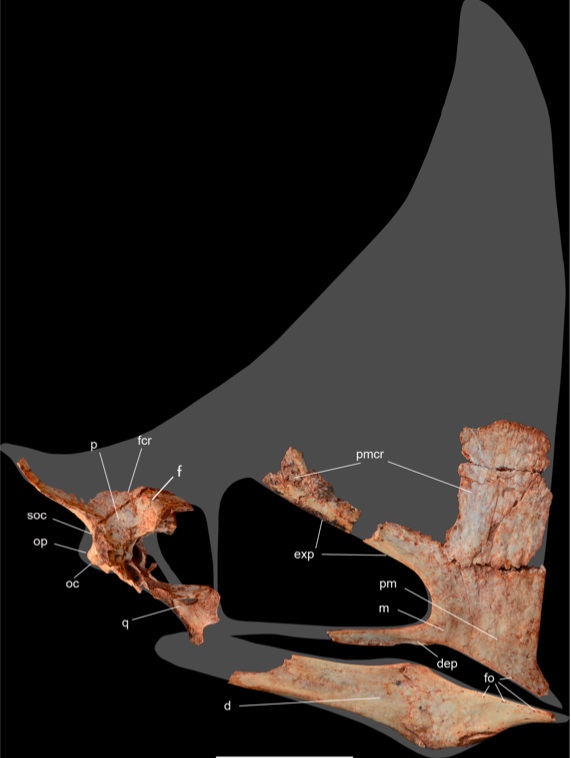

Adult skull

Fragments of head bones from an adult, shown how they would have appeared on the animal.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Head bones

Some of the head bones from the ancient reptile.

Bone fragments

The ancient creatures probably lived around a desert oasis 80 million years ago. As they died, the bones were carried into the lake by desert storms and preserved indefinitely. The different stages of degradation probably reflect how long the animals were exposed to the elements before being submerged, the authors wrote in the paper.

Tia is the managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.