Whee! Whales and Dolphins Squeal with Delight

Almost like giggling children, dolphins and whales squeal with delight when they get a fishy treat, a new study finds.

These marine mammals are known to use buzzing sounds to navigate and communicate when hunting for food. But the animals also emit victory squeals in response to a reward, or merely the promise of one, researchers say.

Sam Ridgway, president of the National Marine Mammal Foundation in San Diego, has spent most of his life studying beluga whales and bottlenose dolphins, to understand how deep they dive, how fast they swim and how well they hear. In their studies, he and his colleagues train the animals to do things by rewarding them with tasty treats. [See video of dolphin squealing with delight]

"We noticed that each time an animal took a fish, it would make this particular pulsed sound," said Ridgway, co-author of the study, published today (Aug. 13) in The Journal of Experimental Biology.

The dolphin or beluga whale would even make the sound in response to the trainer's signal before he or she gave the reward. "Over the years, we heard it many times," Ridgway told Live Science.

The bizarre sound typically consisted of a rapid series of pulses, usually with an upsweeping tone. Originally, he assumed the sounds were signals to fellow animals that food was nearby. But when his wife suggested the squeals resembled the sounds of joyful children, Ridgway decided to find out if she was right.

Victory squeals

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ridgway and his colleagues trained bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and belugas (Delphinapterus leucas) to perform tasks such as diving, and used a whistle or buzzer to signal that the animal would be rewarded later. The animals consistently made the squealing noises after hearing the signal, even long before the reward came.

The researchers dubbed the sounds "victory squeals," because the animals seemed to be celebrating their reward.

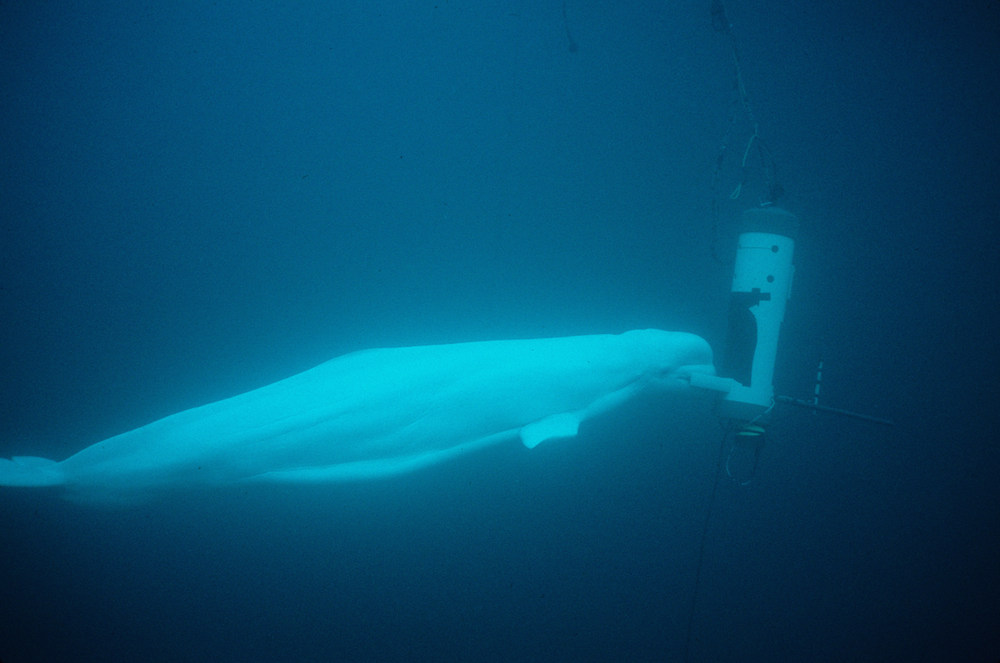

As part of the study, the researchers trained two rescued belugas and a dolphin, both raised in captivity, to dive in the open ocean and turn off an artificial buzzer by pressing a button. (Interestingly, the animals perform the task willingly, allowing themselves to be returned to captivity afterward.) The researchers used underwater microphones to record the sounds.

While at depth, the animals made victory squeals right after they turned off the buzzer, well before coming up to the surface, the researchers found.

Many animals that echolocate, or use sound to navigate, have been known to produce similar sounds. Bats make what scientists call a "terminal buzz" when they zero in on their insect prey. Beaked whales also buzz when they close in on squid, and sperm whales have been known to make creaking sounds when catching their food.

But unlike these animals, the dolphins and whales in the study made sounds after they got a fishy reward, suggesting the sounds were exclamations of delight. To explore this further, the researchers turned to brain chemistry.

Brain pleasure centers

When a mammal — whether it's a rat or a human — gets a reward, it triggers a flood of the chemical dopamine to the brain's pleasure centers.

It makes sense that the brain would reward something like food, Ridgway said. "We have to have a system in our brain that's rewarded by food if we're going to survive well," he added.

In previous experiments, when researchers electrically stimulated these regions in the brains of rats, the animals appeared to experience pleasure. Similar experiments in monkeys have shown the brain releases dopamine about 100 to 200 milliseconds after a rewarding stimulus, such as food.

The researchers measured the time when the dolphins and whales in the study made their victory squeals, and found that dolphins squealed 151 milliseconds after the reward signal and belugas did so 250 milliseconds afterward, indirectly suggesting the animals were squealing in response to a dopamine surge.

Whales and dolphins have a wide range of emotions, and are very expressive, Ridgway said — "maybe more than any other animal [that] expresses their emotions through sound."

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.