Humanity's Longest-Lasting Legacy: Miles of Holes

It's estimated that humans have altered over half of the planet's surface, and those changes are easy to see – the ice sheets are melting, forests are shrinking and species are going extinct.

People have changed the planet so dramatically that some geologists think the Earth has entered a new phase in its geological timeline, named the "Anthropocene." But what about the marks humans are leaving deep underground?

"Because it's not in our immediate living environment, it doesn't seem as significant," said Jan Zalasiewicz, a senior lecturer in palaeobiology at the University of Leicester, in the United Kingdom. But, as Zalasiewicz and two of his colleagues argue in a new study, human activity below the surface is permanently changing Earth, and a sprawling web of holes from mining and energy exploration provides more evidence the planet has entered the Anthropocene. [World's Weirdest Geological Formations]

Out of sight, out of mind

The distance to the center of the Earth is roughly 3,960 miles (6,373 kilometers). Animal life stops 1.2 miles (2 km) below the surface — the depth where miners discovered deep-dwelling worms in South African gold mines. All known microbial life stops at a depth of around 1.7 miles (2.7 km). But humans have left a permanent mark well beyond those depths, geologists say.

When an animal dies, it only leaves behind one skeletal record of itself, but the same animal might leave hundreds of so-called trace fossils in the form of burrows. Most animals leave behind trace fossils a few inches deep. The deepest burrowers are Nile crocodiles, which dig dens up to 39 feet (12 meters) deep. The deepest-reaching plant roots belong to the Shepherd's tree in Africa's Kalahari Desert, which can reach 223 feet (68 m) deep. Humans also leave trace fossils behind, but these typically reach as deep as 7.6 miles (12.3 km) and are permanently changing rock layers.

"No other species has penetrated to such depths in the crust, or made such extensive deep subterranean changes," the researchers wrote in a study published online July 24 in the journal Anthropocene.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Permanent changes

Humans' first underground foray came during the Bronze Age, when people began digging shallow mines in search of flint and metals. The Industrial Revolution of the 1800s sent humans even deeper below the surface. Still, many of the disturbances, like water wells, sewage systems and subway lines, were relatively shallow and extended less than 330 feet (100 m) below the surface. Only after 1950, a period referred to as the "Great Acceleration" by some geologists, did humans really plunge below 330 feet, Zalasiewicz and his colleagues explained.

Growing demand for resources led to more mining to collect coal and other minerals. In most cases, mining only extends several hundred feet deep, but gold mines in South Africa reach almost 3 miles (5 km) below the surface.

More and more boreholes have also appeared over the last several decades. Some boreholes are drilled to harvest geothermal energy. But others are used to pull out natural material from the Earth, such as hydrocarbons, natural gas and ores. The narrow borehole shafts are then filled with other materials, including mud, concrete or solid waste. If all the world's oil boreholes were stacked on top of each other, they would span over 31 million miles (50 million kilometers). That's roughly the distance between Earth and Mars, according to the researchers. Or, put another way, for every human on Earth, there are about 23 feet (7 m) of boreholes. Oil pulled from deep boreholes is often replaced with water that seeps in from neighboring rocks or with carbon dioxide that is pumped in during a process called carbon sequestration. [Top 10 Ways to Destroy Earth]

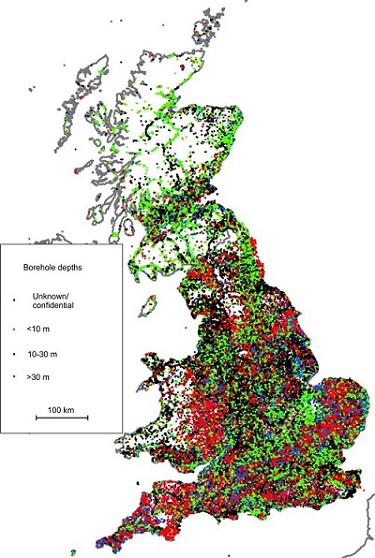

At 7.6 miles (12.3 km) long, the Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia is the deepest hole in the Earth's surface made by humans. (It was drilled in northwestern Russia in the 1980s as part of a scientific investigation.) There are roughly 1 million boreholes in Great Britain alone, according to Zalasiewicz.

Underground nuclear tests have also left their mark, the researchers note. Test sites often contain broken-up and melted underground rocks and disturbed water tables. Huge underground caverns hold stored radioactive waste from the tests.

These human-made changes below the surface will stay there, protected from the natural erosion and weathering that happens above the surface. The web of mines and boreholes "arguably has the highest long-term preservation potential of anything made by humans," Zalasiewicz and his team of researchers wrote. The scientists estimate it will take millions of years for weathering and erosion to uncover tunnels just a few miles below the surface.

A new geological phase?

The geological time scale is a record of how the Earth's surface environment and core, mantle and crust have changed over the planet's 4.6-billion-year history. The timeline is divided into sections called epochs that each define a different age in Earth's geologic history. The epochs are separated by momentous events, such as mass extinctions and ice age melts. Right now, the Earth is in the Holocene epoch that began about 11,700 years ago, Philip Gibbard, a geologist at Cambridge University, told Live Science. The Holocene covers the entire written history of humanity and includes the influence humans have had on the Earth's ecosystems.

Some geologists think that the acceleration of human activity in recent generations is enough to mark the start of a new geological epoch, dubbed the Anthropocene. Many scientists have jumped on board and are using the term, but the epoch has no official start date and is not recognized by the International Commission on Stratigraphy – an organization that aims to provide a standard global geological time scale.

Gibbard argued that human activity is already the basis for the current Holocene epoch.

"It is characterized by the presence and activity of humans," Gibbard said. "If you accept that definition, then you can't use the same definition for the term 'Anthropocene.' You can't play the same card twice."

There's no doubt that humans are influencing geology, but what's happening now is a "logical development of what's happened in the past," Gibbard said.

Getting an epoch recognized as an official phase on the geological timeline is a complicated process, Zalasiewicz said. The idea must pass several tiers of boards of approval. Zalasiewicz and a team of researchers hope to present a case for adding the Anthropocene epoch by 2016, but they still have a ways to go.

One major problem is that scientists don't agreement on where the boundary between the Holocene and Anthropocene epochs should be drawn, Zalasiewicz said. Opinions range from 5,000 years ago to 60 years ago. But as resources become scarcer and the threat of climate change increases, Zalasiewicz said the concept of the Anthropocene could help change the way people think about the environment.

"[The] Anthropocene could help put the current changes into a deep-time context," Zalasiewicz said. "Right now, we tend to make comparisons within the human slice of history only, but what are the effects on a larger scale?"

Follow Kelly Dickerson on Twitter. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.