Too Cloudy? Change the Weather with New Photo-Editing Tech

Whoever said you can't control the weather was wrong. A new photo-editing program lets you decide if you're a rainy day kind of person or if you prefer bright and sunny afternoons.

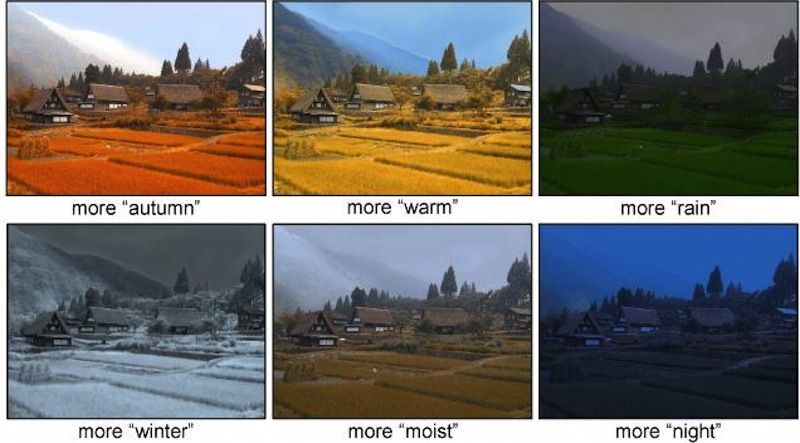

The new photo-editing algorithm allows people to control certain features of outdoor photographs, known as "transient attributes," which include weather, time of day and even the season. Users can decide how they want their photograph to look by sending simple text commands to an interactive database. Making a photo a touch drearier is as simple as sending a command to the database that reads "more rain," according to the researchers who developed the new technology.

Normally, photographers would need to invest in expensive software, such as Adobe Photoshop, in order to make these types of changes to a photograph, said James Hays, an assistant professor of computer science at Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island, who developed the new algorithm. [Photo Future: 7 High-Tech Ways to Share Images]

The high price tag and steep learning curves associated with many existing photo-editing programs inspired Hays to create a tool that makes editing pictures easier for amateurs, he said.

The algorithm avoids veering into expert territory by using a process known as machine learning. In this process, computerized systems automatically learn and fine-tune their behaviors over time. For this particular technology, the researchers first had to teach the computer algorithm what different attributes look like.

They chose 40 attributes or descriptive qualities, some of which were fairly simple to replicate in a photo, such as cloudy, sunny, snowy, rainy and foggy conditions. They also chose more-subjective attributes — things like gloomy, bright, sentimental, mysterious and calm.

The researchers compiled a database with over 8,000 photos taken by more than 100 webcams stationed around the world. The cameras all took photos of the same scenes at different times of day, during different seasons and in different types of weather conditions.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers assigned specific attributes to each photo. For example, a photo taken in broad daylight on a mountaintop in the middle of winter might be classified as "sunny, snowy, winter." Once categories were assigned, the machine-learning algorithm processed the photos, along with their assigned attributes.

"Now, the computer has data to learn what it means to be 'sunset' or what it means to be 'summer' or what it means to be 'rainy' — or at least what it means to be perceived as being those things," Hays said in a statement.

Now that the algorithm has learned what these attributes look like, it can recreate them in other photographs. It does this by making what Hays called "local color transforms." In other words, the algorithm splits the photo into different regions of pixels and uses its knowledge of what different attributes are supposed to look like to determine how those regions should change when they're assigned a certain attribute.

“If you wanted to make a picture rainier, the computer would know that parts of the picture that look like sky need to become grayer and flatter," Hays said. "In regions that look like ground, the colors become shinier and more saturated. It does this for hundreds of different regions in the photo."

To test how the photo-editing algorithm compares to more-traditional photo-editing methods, the researchers asked a group of participants to rate the altered photos. Participants compared the algorithm-edited photos to photos edited by more-traditional means.

Photos altered by the algorithm performed well in the survey, with 70 percent of participants preferring the edits performed by the algorithm to those performed by more-traditional editing technologies.

Follow Elizabeth Palermo @techEpalermo. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Elizabeth is a former Live Science associate editor and current director of audience development at the Chamber of Commerce. She graduated with a bachelor of arts degree from George Washington University. Elizabeth has traveled throughout the Americas, studying political systems and indigenous cultures and teaching English to students of all ages.