Bad Memories Turned to Happy Ones in Mice Brains

Memories are often associated with emotions, and these feelings can change through new experiences and over time. Now, using light, scientists have been able to manipulate mice brain cells and turn the animals' fearful memories into happy ones, according to a new study.

Memories are encoded in groups of neurons that are activated together or in specific patterns, but it is thought that neurons in different brain regions encode different aspects of a memory of an event. For example, the place where an event occurred and the emotion associated with it may be stored in different places.

In the new study, researchers examined whether it is possible to selectively change one part of a memory — the emotion attached to it. They made male mice form fearful memories by giving them painful electrical shocks, or form pleasant memories by letting the animals interact with female mice. [Why You Forget: 5 Strange Facts About Memory]

Later, using light to control the activity of neurons (a method called optogenetics), the researchers evoked the fearful memories every time the mice went to a certain corner of their cage, which led the mice to avoid that corner. In mice that had formed pleasant memories, the researchers used those memories to make a certain corner look attractive to the rodents.

In the last step, to reverse the associations between a place and an emotion, the researchers evoked only the "place" part of the fearful memories, while letting the mice interact with female counterparts. As a result, the mice were no longer afraid of that specific corner of the cage.

The researchers were also able to do the reverse, and turn positive memories to fearful ones, according to the study published today (Aug. 27) in the journal Nature.

Shaping memory fragments

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

It is well-known that memories are subject to change, and may even get slightly rewritten each time we recall them during a new experience, studies suggest.

However, scientists do not entirely understand the brain mechanisms that enable memories to change and that even allow us to feel different emotions about those memories. Elucidating these mechanisms could help scientists one day develop new therapies for conditions such as depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.

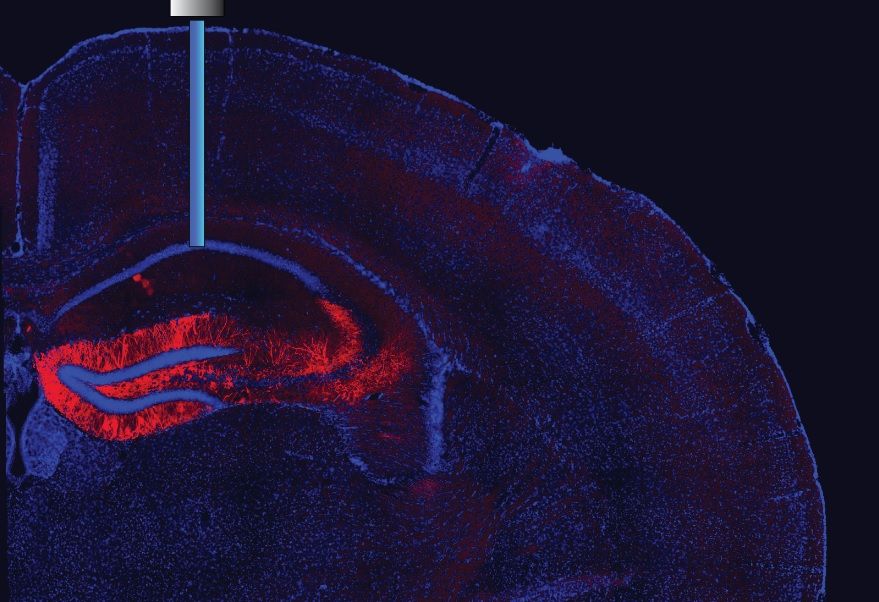

In the new study, the researchers looked at neurons in a brain structure called the hippocampus, which is thought to encode the context of memories, such as where an event happened. The researchers also looked at neurons in another brain structure, the amygdala, which is believed to encode emotions.

The mice in the study were genetically engineered to make tracking their memories easier. As the animals' fearful or pleasant memories were formed, a light-sensitive protein was expressed in the neurons that encoded the new memories. This way, the researchers were able to tag these neurons, and later use light to reactivate the memory those brain cells held.

The new experiment worked because the scientists tackled the contextual and emotional aspects of the memory separately. When the researchers activated the neurons in the hippocampus, it evoked the contextual part of the memory, while new events the mouse was experiencing rewrote the emotional part of the memory. This led to a new memory of the same place but with a different emotional association, the researchers said.

Looking at the cells under the microscope, the researchers confirmed that the relationship between the memory-holding neurons in the hippocampus and those in the amygdala was altered after the scientists' manipulations, suggesting that the connection between the two brain regions is indeed malleable.

The new experiments followed previous studies by the same researchers last year, in which they implanted false memories in mice. In those studies, the researchers activated neurons to make mice remember a previous experience as the animals were undergoing a new and different experience. This made mice form a memory of the mixture of the two experiences, which in real life had never happened.

Email Bahar Gholipour. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.