Tree Infesting Insects Love the City Heat (Op-Ed)

This article was originally published at The Abstract. The publication contributed the article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

About a year ago, I found myself sitting ruefully in a patch of chiggery grass by the side of the road near the little town of Bahama, North Carolina, waiting for a tow truck. I had stuck the lab pickup firmly in a ditch. It was tilted at an embarrassing, sickening angle and had one wheel lodged against the mouth of a culvert. Helpful passers-by with chains and four-wheel drives kindly offered to pull me out, but really only made matters worse.

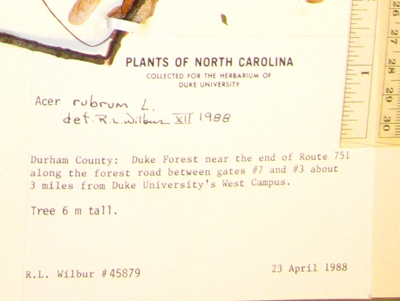

My memory is already fuzzy about the sequence of events, but somewhere in there—between slipping into the ditch, the failed rescue attempts, and the final arrival of the giant tow truck—I did actually hike into the woods and get what I came for: eight slender red maple branches, clipped from trees growing in NC State’s Hill Forest.

I found my way to this particular spot, ditch and all, by following the trail of a plant biologist who had collected maple branches there more than 40 years ago during the height of the Nixon administration and the Vietnam War. In those days, the forest was cooler. The fevered dog days of summer now average about 1.4 degrees C (about 2.5 degrees F) hotter than they did then—and that should make a difference to the trees and the insects that live on them.

The scales drink tree juices, so more scales are bad for trees. A couple of degrees warming can make the difference between a stately shade tree and a sad, bedraggled specimen with dead branches, sparse leaves, and grimy, scale-encrusted bark. Specifically, it ought to make a difference to gloomy scale insects. These little sap-sucking insects seem to like it hot. My colleague Adam Dale has been studying gloomy scales in the city of Raleigh, and he’s found that street trees in the hottest parts of the city have far more scales — sometimes 200 times more — than those in the cooler parts of the city.

We thought that if warming gives scales such a powerful boost in the city, global warming could do the same thing for scale insects in rural forests. But we still had no direct evidence that what happens in the city represents what happens in rural areas over time.

This seemed like hard evidence to get. Unlike birds and butterflies, the drab, millimeter-long gloomy scale has not invited enthusiastic long-term monitoring. But perhaps we could scavenge scale-insect information from another source—and this is why I became extremely grateful to scores of plant biologists like the one who archived a foot-long maple twig from Hill Forest in 1971.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

These historical plant specimens are stored in collections known as herbaria, where they are affixed to stiff pieces of paperboard, labeled, and stacked in mothball-scented cabinets. It turns out that many of these old twigs still have scale insects intact, stuck firmly but inconspicuously to the spots where they once lived.

It made perfect sense that they would be there, but it still felt outlandish when, only 12 branches into my first search in the UNC Herbarium, there was a gloomy scale—the same species that burdens our urban red maples. It was beautifully preserved, looking like it was collected last week instead of 30 years ago. Even on 100-year old branches, the scales looked perfect.

So I counted them. And kept counting them on more than 300 historical specimens from the southeastern US, then matched up their abundance with historical temperatures for the year and location where each specimen was collected.

There it was: During relatively cool historical time periods, only 17% of branches had scale insects. But during relatively hot periods, 36% were infested. In other words, scale-infested branches were more than twice as common during hot periods than cool periods—exactly as we would expect if scale insects benefit from warming in rural forests as they do in the city. Furthermore, the most heavily infested twigs were ones that had grown at temperatures similar to those of modern urban Raleigh.

But the historical specimens weren’t the whole story. The past several years have been warmer than even the historically warm time periods, so to test our prediction, we needed to go back to places where those old branches were originally collected, and see if their scale infestations had actually gotten worse.

Thanks to the careful records of those past plant collectors, I was able to track down 20 of the forest sites across North Carolina where red maple branches were collected in the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ‘90s (and only put the truck in a ditch at one of them). At 16 of the 20 sites, gloomy scale populations were denser than they were on the original branches from the same locations. Overall, I found about five times more scales in 2013 than in the earlier decades.

This isn’t good news, but it’s also not time to panic about gloomy scales killing our forests. Although the rural scale insects clearly benefited from warming, just as they do in Raleigh, they still never got as abundant as the ones we see in town. The reasons for that difference are an open question (I have some guesses, but that’s a different story). So, although I’d put money on gloomy scales getting more common in rural North Carolina over the next several decades, I wouldn’t yet say how much more common.

But this really isn’t just about gloomy scale. It’s about cities as an advance guard of climate change. If we can look at scales’ response to urban warming and correctly predict their increased abundance due to global warming, can we do it for other organisms, too? Can we do it for functions, like pollination and biological control of pests?

I hope we can start watching urban ecosystems for problem insects and using that information to stand forewarned about future ecological changes in natural areas. The experiments we have made by paving our cities and making them heat up may have much more to tell us about how organisms will handle future warming.

Editor’s Note: This is a guest post by Elsa Youngsteadt, a research associate in NC State’s Department of Entomology. The post regards an Aug. 27 paper lead-authored by Youngsteadt. More information on the paper is also available here. The post first ran on NC State’s Insect Ecology and Integrated Pest Management blog.

This post is based on a new study: Youngsteadt, E., Dale, A.G., Terando, A.J., Dunn, R.R. and Frank, S.D. 2014. Do cities simulate climate change? A comparison of herbivore response to urban and global warming. Global Change Biology. doi: 10.1111/gcb.12692.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google +. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.