Ancient Mammal Relatives Were 'Night Owls'

Mammals were long thought to have evolved nocturnal lifestyles as a way to co-exist with dinosaurs, but new research finds that nighttime behavior may have evolved 100 million years earlier than mammals did.

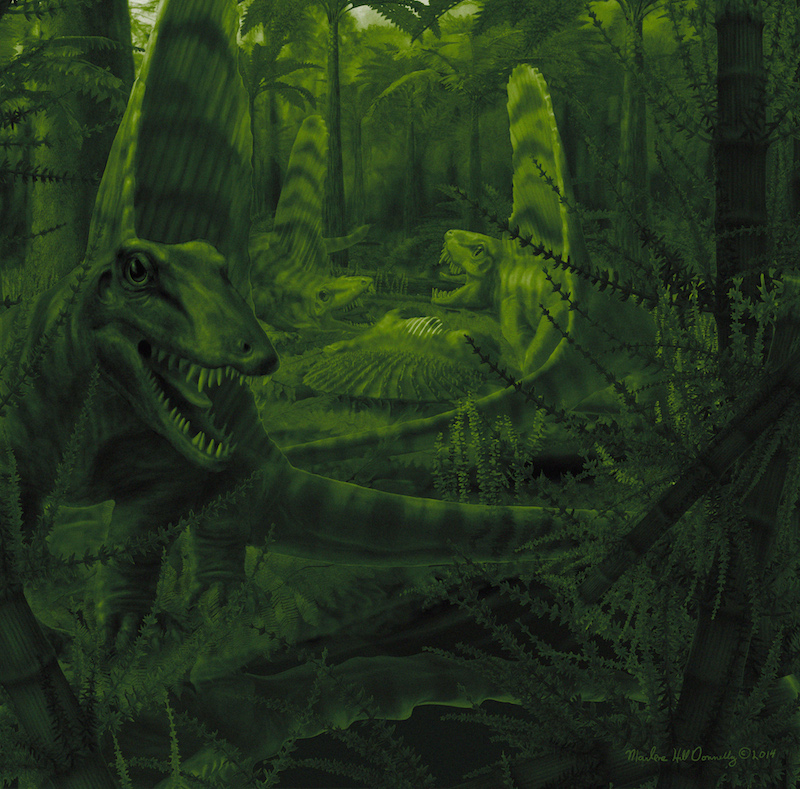

The eye bones of ancestors of modern mammals that lived more than 300 million years ago, such as the sail-finned carnivore Dimetrodon, suggest that at least some of these animals were already active at night, researchers say.

"Traditionally, dinosaurs were considered day-active, and mammals were regarded as living in the shade of them, living at night," said Lars Schmitz, a biologist at Claremont McKenna, Pitzer and Scripps colleges in Claremont, California, and co-author of the study, detailed today (Sept. 3) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. [Gallery: Evolution's Most Extreme Mammals]

But recent studies by Schmitz and others have shown that some dinosaurs were probably nocturnal, so the scientists suspect nighttime behavior arose much earlier than with the first mammals.

Approximately half of all living land mammals are nocturnal, and many more are active at twilight, the researchers said. Humans and other primates are some of the exceptions; they're active primarily during the day. But it would be "a bit self-centered" to assume diurnal behavior is the norm, Schmitz told Live Science.

Mammals are part of a larger group, called synapsids, that includes mammals and all extinct relatives that were more closely related to living mammals than to birds, reptiles or amphibians. The oldest synapsid fossils date back to 315 million years ago, and the first mammals don't appear in the fossil record until about 200 million years ago, the researchers said.

To investigate when nocturnal behavior first evolved, Schmitz and his colleagues from The Field Museum in Chicago examined some of the more ancient synapsid fossils from museum collections in the United States and South Africa. "We tried to look at bones that may be related to their ability to see at night," Schmitz said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Specifically, the researchers were interested in tiny, ringlike bones in the eye known as scleral ossicles, which provide clues to the size and shape of the eyes. Modern mammals lack these bones, but they are found in the eyes of many other vertebrates. The bones are very fragile, however, so they aren't often preserved in fossils.

The researchers used a statistical technique to analyze the tiny bones, comparing them with the bones of living animals to prove that the method was robust.

The findings suggest that some synapsids were active during the daytime and others during the nighttime, and some were active at twilight. Interestingly, some of the oldest synapsids they looked at, including Dimetrodon, had eyes whose size indicates these animals were likely active at night.

The findings help researchers understand the biology of these mammalian ancestors. "How were they living? How were they dividing resources?" Schmitz said. "With these little puzzle pieces, we can start building this image of what life may have been like 250 million years ago."

Jörg Fröbisch, a biologist at Humboldt University of Berlin, in Germany, who specializes in synapsid evolution, said he was "very excited" about the findings. "All the evidence seems to point to the fact that there was a wide variety of [daytime] behavior" among these mammalian ancestors, said Fröbisch, who knows the authors of the new study but was not involved in it.

Fröbisch's colleague at Humboldt, evolutionary biologist Christian Kammerer, agreed."Mammals are thought to be ancestrally nocturnal, but this study demonstrates that this was not some crucial novelty in mammalian evolution: There had been nocturnal members of the mammalian stem lineage for a hundred million years," Kammerer told Live Science.

However, Kammerer cautioned that the results should not be interpreted as definitive, as the activity patterns in living animals are "often messy," and animals may be active during both day and night.

"The Field Museum shouldn't throw out its mural of a Dimetrodon hunting by daylight quite yet," he said.

Follow Tanya Lewis on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.