The 'Normal' American Family Is a Myth

The change in family structure over the past 50 years is not a simple march from a "Leave It to Beaver"-style two-parent household to Murphy Brown-esque single working moms. In reality, new research finds, the name of the game is now diversity.

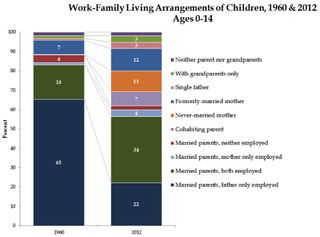

There is no single "normal" in the modern American family, according to a new report prepared for the Council on Contemporary Families. Most commonly, children (34 percent) live with married, dual-career parents. However, no single family style is in the majority.

"We have not replaced one ideal family type with another," said Philip Cohen, a sociologist at the University of Maryland. "We have replaced one ideal family type with what we call a 'peacock's tail' in the report, because it fans out." [I Don't: 5 Myths About Marriage]

Changing families

Cohen used data from the U.S. Census and from national surveys on family life to reconstruct the family arrangements of Americans in 1960 and 2012.

In 1960, the American family showed a "peak conformity," Cohen told Live Science. That year, the age at first marriage was the youngest, the marriage rate was at its highest, and the number of extended families living together in multigenerational households was the lowest.

That year, 65 percent of children under age 15 lived in a family with married parents in which the father was the breadwinner — the "Leave It to Beaver" ideal. Another 18 percent had married parents who were both employed. Only one child in 350 lived with a mother who had never been married. The vast majority of the single motherswere divorced, widowed or separated, and about 7 percent of children were growing up in those households.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In 2012, no family type held a majority. The number of children with married parents and only a father working dropped to 22 percent, while children raised by dual-income married parents rose to 34 percent. Eleven percent of kids lived with a never-married mother and 7 percent with a parent cohabiting with a romantic partner. About 3 percent of children lived with a single father.

In 1960, two children chosen at random had an 80 percent chance to be growing up in the same sort of family structure as each other. In 2012, that chance was only 50 percent, Cohen found.

Parenting and policy

One consequence of all this diversity is the cultural confusion and conflict visible on any mommy blog or parenting website.

"People are really sort of on their own figuring out how to make their family life work, and that's one reason why you have the huge advice and parentingindustry," Cohen said. The search for role models may also help to explain the intense interest in celebrity families and marriages, like the recent Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie wedding.

"People get reassurance from conformity," Cohen said. "Not that everybody wants to conform with everyone else, but they like a model."

The implications go beyond friction at playgroup, however. Many social welfare programs are set up with married families in mind, Cohen said, but people's real lives are far more diverse. For example, he said, Social Security benefits based on a spouse's earnings may leave never-married or early-divorced people at a disadvantage in retirement.

"Flexibility has got to be our approach," Cohen said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook& Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.