El Nino Watch: 6 Months and Still Counting

For months now, the tropical Pacific Ocean has been flirting with blossoming into a full-fledged El Niño state: Waters off the coast of South America have warmed, a hallmark of the climate phenomenon, but then cooled, only to warm once again. Winds, which normally blow east-to-west have made tentative moves in the other direction, another key criteria, but the bottom line is that the whole El Niño package hasn’t come together.

So, is this El Niño going to happen or not?

“Most likely” is the answer from forecasters with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s Climate Prediction Center and the International Research Institute for Climate and Society at Columbia University, who issue monthly forecasts.

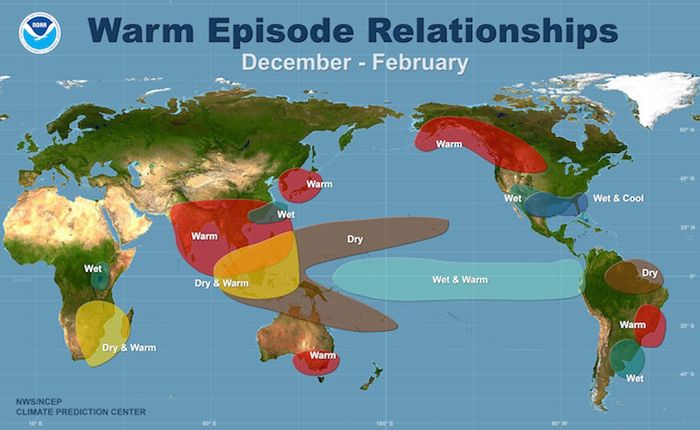

Whether or not the El Niño forms, when it does so and how strong it is has a bearing on theweather and climate impacts it can have around the world. It is thought that even the neutral-but-tending-toward-El Niño conditions in place right now are helping to tamp down Atlantic hurricane activity, but only strong El Niños are linked to enhanced rains in Southern California, which the state desperately needs.

How Will We Know When El Niño Finally Arrives? El Niño Expected to Limit 2014 Hurricane Season Why Do We Care So Much About El Niño?

The latest update, issued Thursday, notes that some aspects of the tropical Pacific’s behavior look more promising than they did at the time of the last update in early August, but keeps the likelihood of an El Niño developing at 60 to 65 percent.

“We still believe that the event will occur,” CPC forecaster Michelle L’Heureux told Climate Central.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

When might this happen?

Sometime in the September to November time frame, the CPC forecast said. Once the El Niño does form, it is expected to continue into the early part of 2015. The event, though, is only expected to be a weak or moderate one, L’Heureux said.

El Niño is the warm phase of the larger phenomenon called the El Niño-Southern Oscillation. During an El Niño, the waters in the eastern part of the tropical Pacific are warmer than usual and the trade winds that normally blow from east to west weaken or even reverse. (During its counterpart, La Niña, the eastern waters are cooler and the normal trade winds are intensified.)

The temperature threshold that forecasters use to mark an El Niño is a warming of 0.5°C (0.9°F) — the sea surface temperatures in a particular area of the tropical Pacific must have met this condition for a month and be expected to do so for the next three months.

Temperatures have hit that mark, but then were not expected to persist, and over the summer, they even cooled somewhat.

Things seem to be back on track now, with temperature differences hanging around the 0.5°C mark. This is also where most models have been hovering in recent runs, just eking past the El Niño threshold.

“It’s actually been a little unnerving” to look at the models, L’Heureux said. (In 2012, forecasters called for an El Niño to form, but it eventually fizzled out. So far this year, the models haven’t dropped the development of the phenomenon like they did then.)

The recent warmer waters came after a burst of westerly winds touched off what is known as a Kelvin wave, when warmer waters travel below the surface of the water from west to east. What exactly its full impact will be won’t be known until later this month or into October, though.

El Niño watchers “have to be patient and see what happens,” L’Heureux said.

You May Also Like: Wind, Solar Boosting Investment in Power Lines Visualize It: Old Weather Data Feeds New Climate Models For Air Pollution, Trash Is a Burning Problem Climate Change Ups Odds of a Southwest Megadrought

Follow the author on Twitter @AndreaTWeather or @ClimateCentral. We're also on Facebook & other social networks. Original article on Climate Central.

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.