Ancient 'Toothy' Dolphin Fossils Found in Peru Desert

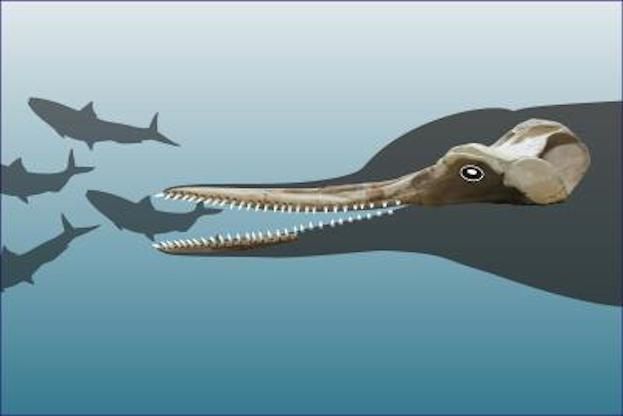

The dusty Pisco-Ica desert stretches along the coast of southern Peru, but more than 16 million years ago it may have been covered with sparkling water and home to a now-extinct family of dolphins, known as squalodelphinids, according to new findings.

The desert is a haven for marine fossil hunters — paleontologists have found whales with fossilized baleen, a giant raptorial sperm whale and a dolphin that resembles a walrus, researchers say.

The new findings include the fossils of three dolphins, two of which have well-preserved skulls. A thorough skeletal analysis suggests the dolphins are not only a new species but also related to the endangered South Asian river dolphins living in the Indus and Ganges rivers in India today, the researchers found. [Deep Divers: A Gallery of Dolphins]

"The quality of the fossils places these specimens as some of the best-preserved members of this rare family," lead study author Olivier Lambert, of the Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, said in a statement.

River dolphins are an unusual breed. Unlike other dolphins, they live in muddy freshwater rivers and estuaries, and they have a long, narrow, toothy beak and small eyes with poor vision, said Jonathan Geisler, an associate professor of anatomy at the New York Institute of Technology, who was not involved in the study.

The three fossils do not appear to be ancestors of other river dolphins, including those of the Amazon or the Yangtze rivers, the latter of which may be extinct, said John Gatesy, an associate professor of biology at University of California, Riverside, who was not involved in the study.

"They're three of a kind," Gatesy said. "Three independent lineages."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers have long tried to determine how river dolphins fit into the family tree. "It's not normal for a whale or a dolphin to live in freshwater these days," Gatesy said. "What seems to have happened is they've independently adapted to living in freshwater conditions."

The new findings help answer that question, at least for the South Asian river dolphins, experts say.

"It's helping flesh out this pretty poorly known extinct family that helps tie this oddball living species into the evolutionary tree," Geisler said.

Researchers have uncovered other squalodelphinid specimens in Argentina, France, Italy and on the East Coast of the United States, but fossils of these medium-size dolphins are still rare. The modern families of tooth whales, porpoises and dolphins diverged in the early Miocene epoch, about 20 million to 24 million years ago, making any marine fossils from that time period valuable, Geisler said.

The new, extinct species was named Huaridelphis raimondii, after the ancient Huari culture of the south-central Andes and coastal area of Peru that existed from A.D. 500 to 1000, and "delphis," which is Latin for dolphin. The species name celebrates Italian scientist Antonio Raimondi (1826-1890), who found fossils of whales in Peru, the study reports.

Given the abundance of fossils in the Pisco-Ica desert, paleontologists may soon find and name other squalodelphinid remains, Giovanni Bianucci, of the Universitá degli Studi di Pisa and an author on the study, said in a statement.

"Considering the richness of the fossil localities recently discovered, other new extinct dolphins from the same geological age will certainly soon be found and studied," Bianucci said.

The study was published today (Sept. 9) in the journal Vertebrate Paleontology.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.