Patience, Persistence Reveal Sharks' True Nature

Ila France Porcher is a self-taught, published ethologist and the author of "The Shark Sessions." A successful wildlife artist, she documented the behavior of animals she painted. In Tahiti, intrigued by the native sharks, she launched an intensive study to systematically swim with them and record their actions, following the precepts of cognitive ethology. Credited with the discovery of a way to study sharks without killing them, Porcher has been called "the Jane Goodall of sharks" for her documentation of their intelligence in the wild. She contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

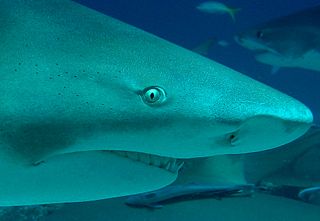

The ancestors of modern sharks were already roaming the oceans 455 million years ago, when green plants were first transforming the land. Their presence now, in the form of more than 470 species split across 14 orders, is woven throughout the marine environment, and they are considered vital to oceanic ecology. Yet humanity has branded them as mindless killers, and is hunting them to the brink of extinction. [One-Quarter of Sharks and Rays at Risk of Extinction]

What are sharks really like?

Sharks: an ethological study

Ethology is the name given to the scientific study of wild-animal behavior in the natural environment, and is a branch of the field of zoology. One of its major principles is to "know your animal," which requires detailed observations of individuals over long periods.

That is especially difficult to achieve with sharks, and prior to my study, such observations were not considered possible. In today's rapid pace of science, it’s far easier to place tags on animals. There are excellent advantages in accomplishing studies of numerous animals by such means, and the popularity of that method is without question, but it often cannot explain, except in the broadest sense, why animals do what they do. And individual animals often don't do what others around them do. It is for this reason that the work of ethologists is important.

In the shallow fringe lagoons of French Polynesia, it was possible for me to observe individual sharks for long periods without the encumbrance of scuba gear, and without the problem of sharks disappearing into the depths. Over a period of 15 years, I searched out and observed reef sharks in the different locations where I lived on two islands in French Polynesia. Their behavior was so intriguing that for seven years I studied them intensively to learn what they were like as animals and individuals. [Social Sharks (Gallery)]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The blackfin reef shark, (Carcharhinus melanopterus) was most common, and in time I identified 600 individuals, and could recognize about 300 on sight.

The females of the species occupied home ranges in the fringe lagoons surrounding the islands, within the barrier reefs, while the males roamed more widely in the ocean on the outer slope. Pups were born in shallow areas used as nurseries, and after about six weeks, they began to move away, remaining in safe refuges of thick coral until they were big enough — at the age of between 2 years and 3 years — to mix with the general population in the lagoon.

Sharks as individuals

Individual differences marked each shark's behavior. Each one had a unique pattern of roaming, under the dual influences of the lunar phase and their reproductive cycle. Some were nearly always present in their home ranges, while others traveled for months at a time. Individual sharks demonstrated different rates of learning, and they varied greatly in their responses to different situations. They had complex social lives and their behavior showed a flexible intelligence.

Sometimes a shark passed the same coral formation at almost exactly the same time each evening for several nights in a row, then disappeared from the area for a year. Sometimes, day after day, a shark could be found in exactly the same place in her home range at a particular time, then the following day she was hunting on the outer slope of the reef at that time. There were some days that all the females left the study area, and others when the residents were circling excitedly with visiting neighbors.

In time I concluded that the sharks were using cognition, rather than reacting automatically to stimuli. Cognition is the term used for thinking in nonhuman animals — the process of knowing through thinking. An animal shows that it is using cognition, rather than trial and error, when it must have referred to a mental representation in order to act as it did.

Many life forms, including invertebrates, are increasingly found to be using cognition in their daily lives, and cognition in fish has been well studied.

Sharks have companions

In my observations, individual blackfin reef sharks tended to travel away from their ranges with preferred companions, other sharks of the same gender, and usually, sharks of about the same age. Some sharks always traveled with the same companion, others changed companions relatively frequently, and a very few generally appeared alone.

Often, travelers were temporarily joined by the residents of the regions through which they roamed. They would follow each other around and swim side by side for long periods. Socializing was clearly important to them, and when many sharks were socializing, they tended to speed up, and seemed to enjoy soaring fast through the area together. They observed no minimal inter-animal distance, and often touched.

Their roaming correlated with the lunar phase, and the thrilled shark congregations that formed as the full moon rose, when visiting sharks were present, were often dramatic. In one example, an older female shark who usually never accelerated suddenly shot vertically up, shook off her remora, and streaked away out-of-sight so fast that the eye could scarcely follow her. Moments later, she rocketed through the scene again, many others soaring with her out of view in the opposite direction.

In fact, over the period of years in which I was observing sharks, I saw something like this many times, not just once. If it only happened once, it could be dismissed as anecdotal.

Roaming in loose contact

The species generally roamed in circular or oval paths of various diameters, which crossed at the center and formed rough figure-eights or cloverleafs. Such patterns brought the sharks repeatedly into contact with each others' scent trails, presumably allowing them to keep track of each other while remaining out of visual range much of the time.

On occasions in which I was traveling with a shark, she would at times catch up to another individual, and swim nose-to-tail with her, or side by side. Then, after resuming her arcing trajectory for a time, she would catch up to another, different shark and briefly swim with her. Had she been targeting the other shark through the vibrations she made, it is unlikely that she would have approached her each time from behind. Nose-to-tail swimming was common — among males and juveniles, as well as the females.

The reef sharks from my observations were acquainted with other individuals whose home ranges overlapped theirs, and as far as I could determine, traveling companions were neighbors at home. Some of these companionships were so strong that the couple visited together for many years. In other cases, sharks who usually traveled together appeared for a time with a different companion, then resumed traveling with their original partner on a future occasion.

As well as documenting the visits of shark companions to the study area, I found pairs and groups of residents from the study area roaming though other regions. Further, some of the resident sharks would often accompany visiting sharks for awhile when the visitors left the area, suggesting that these visits were important to them.

A prerequisite for cognition

By choosing shark companions, and repeatedly reuniting with the same shark while roaming, these sharks demonstrated that they knew each other as individuals, which is the prerequisite for the complex social lives in which cognition is most evident.

Bonnethead sharks have been found to recognize each other as individuals, and it has been documented that at least some species of sharks and rays choose their mates, providing further evidence that this ancient line of animals recognizes others of its own species as individuals.

Yet though they formed companionships, I never saw sharks fighting, and other researchers have not reported fighting among sharks, either. This is one important way sharks differ from mammals and birds. Apparently sharks have companions, but no enemies.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.