Cause of Mysterious Butterfly-Shaped Radar Blob Found

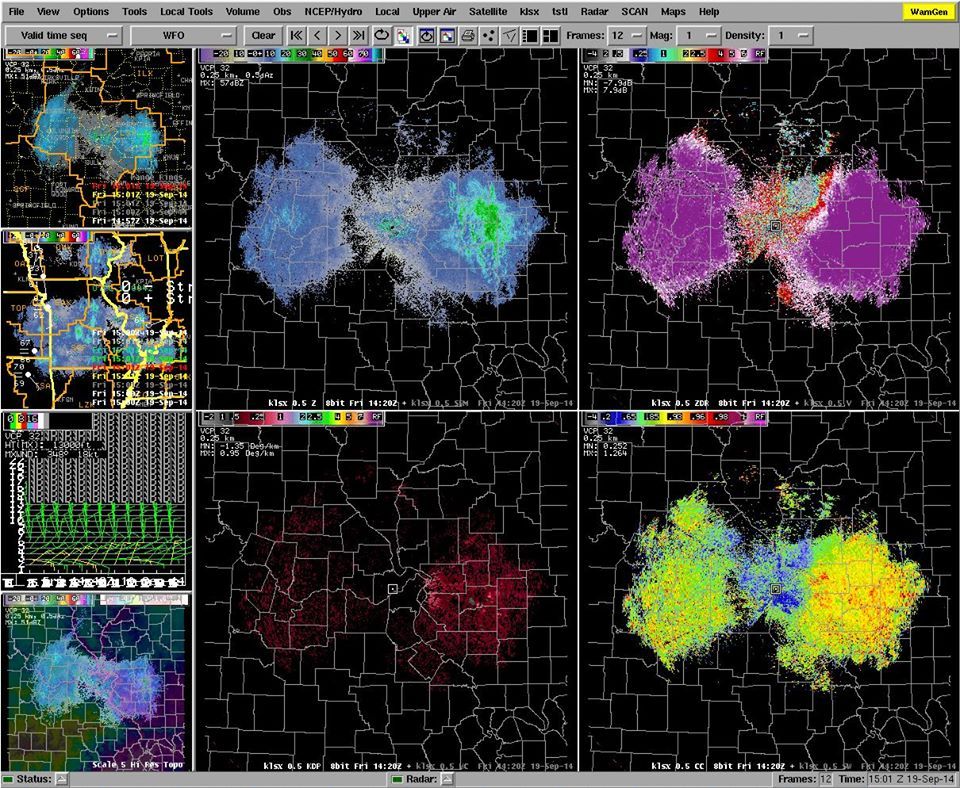

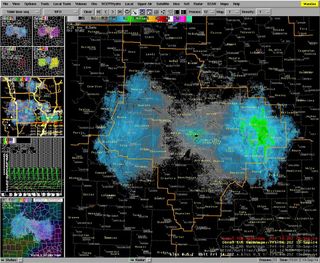

A mysterious butterfly-shaped cloud spotted over St. Louis last week was built from actual butterflies, the National Weather Service said.

In a rare coincidence, a giant swarm of migrating monarch butterflies resembled a butterfly on radar for a short time Friday afternoon (Sept. 19). Forecasters suspect hundreds of monarchs were flying between 5,000 feet and 6,000 feet (1,525 meters to 1,825 meters) above the ground, heading south to Mexico. Though small, their fluttering wings are good radar targets, the National Weather Service (NWS) said on Facebook. No one saw the butterflies, but the radar signals suggest the "targets" were flapping, flat and biological, similar to a monarch.

Hummingbirds are migrating now as well, but the zippy birds prefer to fly at treetop level, ruling out a Hitchcock-like scenario, according to the NWS.

The double-butterfly is not the first time a radar image mirrored its maker. In 2011, a startled flock of blackbirds in Beebe, Arkansas, looked like a bird's head and beak. A strange radar image that puzzled forecasters in Huntsville, Alabama, in June 2013, turned out to be reflective particles used to test military radar. [See Images of the Mysterious Radar Blob over Alabama]

The butterfly-blob's timing matches up with a recent monarch exodus from the Great Lakes region, as tracked by the nonprofit Monarch Watch. The eastern population spends summers spread across the Great Lakes and the northeastern United States and Canada, and then migrates in the fall toward Michoacán, in western central Mexico. (A western population summers in California, but also winters in Mexico.)

The monarchs may have gathered together because of favorable weather conditions. Monarchs take advantage of air currents to soar like birds, conserving energy for their two-month trip to Mexico. Sometimes the butterflies fly in ones or twos, but swarms of dozens or hundreds of stunning orange-winged insects have been sighted by people tracking their migration, according to Monarch Watch.

Exposure to drought, cold temperatures and pesticides along the migration routes and in Mexican forests has triggered a dramatic decline in the monarch population. The numbers hit a record low of 33 million butterflies overwintering in Mexico in 2013.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Most ancient Europeans had dark skin, eyes and hair up until 3,000 years ago, new research finds

1.4 million-year-old skull found in Spain is 'earliest human face of Western Europe'

Liftoff! NASA launches SPHEREx telescope — an infrared observatory that will help JWST solve the mysteries of the universe