One of the most exciting astrophysics discoveries in recent memory may be a mirage.

In March, a team of scientists announced that they had found evidence of primordial gravitational waves, hypothesized ripples in space-time whose existence would suggest that the universe did indeed expand many times faster than the speed of light in the first few instants after the Big Bang, as posited by the "cosmic inflation" theory.

But some outside researchers quickly raised questions about the discovery, which was made using observations by the Background Imaging of Cosmic Extragalactic Polarization (BICEP2) telescope in Antarctica. The supposed gravitational-wave signal, the skeptics said, may actually be a contaminant, the result of dust and gas within our own Milky Way galaxy. [The Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps]

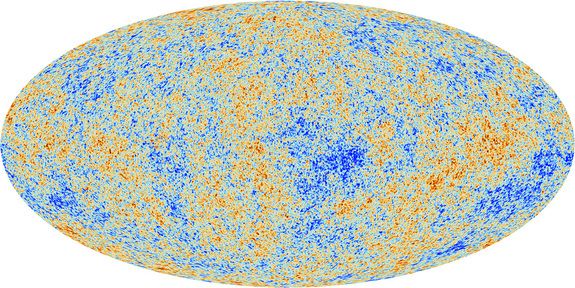

The BICEP2 team saw a polarization pattern known as "B modes" in the cosmic microwave background (CMB), the ancient light left over from the Big Bang that created the universe 13.8 billion years ago. Wide acceptance of the purported find will likely come only if other instruments pick it up, too — in particular, the European Space Agency's Planck satellie, which mapped out the CMB in fine detail from 2009 to 2013.

The Planck team has indeed followed up the BICEP2 result, analyzing data from the same patch of sky in a variety of frequencies that range from 30 gigaherz to 857 gigaherz. (BICEP2 looked in just a single frequency, 150 gigaherz.) And the news is not great for the BICEP2 crew, a new study reports.

"Unfortunately, according to our analysis, the effect of contaminants and in particular of gases present in our galaxy cannot be ruled out," co-author Carlo Baccigalupi of the International School for Advanced Studies in Trieste, Italy, said in a statement.

The new study does not rule out the possibility that BICEP2 really did see the signature of primordial gravitational waves, however. Indeed, Planck scientists are working with the discovery team to see if this could be the case.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"We have started a collaboration with BICEP2. We are directly comparing their data with the Planck data, in the same frequency, 150 GHz, and trying to exploit the image of the contaminants we reach with Planck at other frequencies," Baccigalupi said. "This way, we hope to be able to give a definitive answer. In fact, we might find that it was indeed a contamination, but, given that we’re optimists, we might even be able to exclude it with confidence."

If the discovery is confirmed, Baccigalupi added, it "would open a completely new window onto unknown scenarios in the study of the primordial universe and very-high-energy physics."

The new study from the Planck team will be published Monday (Sept. 29) in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. You can read a preprint of it here: http://arxiv.org/abs/1409.5738

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.