Historic Treaty: Bring Buffalo Home, Heal the Prairie (Op-Ed)

Leroy Little Bear is Professor Emeritus at the University of Lethbridge and Tribal Elder for the Blood Tribe; Ervin Carlson is the Blackfeet Nation Bison Program manager and President of the Intertribal Buffalo Council (ITBC); Angela Grier is a Piikani Tribal Council member; Tommy Christian of the Fort Peck Tribal Council; and Chief Earl Old Person of the Blackfeet Nation is advisor for the National Mammal Campaign and a Tribal Council member. The authors contributed this article to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

For tens of thousands of years, buffalo fundamentally shaped Native American cultures and engineered the ecology of prairie ecosystems. Immense herds grazed and enriched the grasslands and mountain foothills across North America. Acting as a natural bio-engineer in prairie landscapes, they shaped plant communities, transported and recycled nutrients, created habitat variability that benefited grassland birds, insects and small mammals, and provided abundant food resources for grizzly bears, wolves and humans.

More than any other species, the buffalo — American bison , or iiniiwa in Blackfoot — linked native people to the land, provided food and shelter, and became a central figure in our ancient cultures. Following the great slaughter of the 19th century, the buffalo has been missing from most of these lands and our cultures. There is growing recognition that the absence of buffalo has led to deterioration of the ecological integrity of grasslands, diminished the health of our people, and led to an incalculable cultural loss.

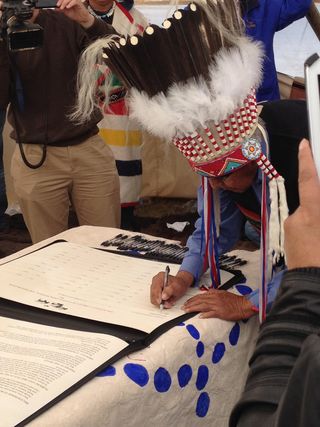

This is why on Sept. 23, we hosted a tribal treaty convention in our Blackfeet Territory to commit the northern tribes and First Nations along the Medicine Line (the international boundary with Canada) to promote the conservation of prairies and the repatriation of American bison.

To achieve our vision, the treaty calls for engagement with researchers and partners in federal, state and provincial governments; farmers and ranchers; conservation groups; and Native American youth. The "Buffalo Treaty" represents an important step by native people to practice conservation while preserving our cultures . We propose that this historic buffalo treaty will be but a first step, begun by native people, to create a national agenda to bring buffalo home and enable an important healing for the egregious treatment buffalo received at the turn of the 19th century.

Collapse of the Great Plains

With the arrival and expansion of European Americans across North America, the northern Great Plains region has undergone more than a century of fragmentation, which has disrupted important ecosystem functions of native grasslands and relegated wildlife to small parcels of protected lands. This fragmentation has had its greatest impact on highly migratory species like buffalo that require large, intact landscapes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Once numbering in the tens of millions, buffalo came to the very brink of extinction due to unsustainable harvest and habitat destruction during the late 1800s. In what was the first wildlife restoration effort in the world, buffalo were saved through the persistent efforts of early conservation champions like Theodore Roosevelt, William Hornaday, Ernest Thompson Seton and others who invented a new conservation model for the world. Although these champions did preserve buffalo through their monumental efforts, it was primarily on small fenced landscapes. Ecological restoration will require extensive, native prairies that can support free-roaming buffalo that can fulfill their natural ecological role — therefore, preserving the prairies is critical to any option for restoring and recovering American buffalo. [A Great American Conservationist: Remembering Teddy Roosevelt ]

Disappearance of wild buffalo in the Great Plains has led to cultural disruption among native people who associate the loss with a national movement to subjugate them. Our people still maintain a deep relationship to the land and wildlife, but unfortunately are no longer able to fully express that relationship because of the absence of buffalo. That loss has diminished the rich, deep relationship that existed before the extermination of these animals.

Restoring some aspects of the physical, spiritual and cultural relationship with buffalo could inspire a new future for the prairie grasslands and its people. Developing a modern, culturally relevant vision for the conservation of iiniiwa could lead to unique opportunities to restore ecological, spiritual and cultural integrity to prairie ecosystems managed by native peoples.

Tribes and First Nations in Canada and the United States own and manage a vast amount of intact prairie habitat across the Great Plains and mountain foothills of the western United States. These intact grasslands provide suitable habitat for American buffalo if they remain intact, unfragmented and in their natural state. Native peoples of the northern Great Plains are culturally disposed to protecting their homelands, connecting with free-roaming buffalo, and have expressed considerable interest in their repatriation to native landscapes. Individually, each tribe may have limited resources and influence to achieve this grand vision of buffalo restoration.

However, our combined voice and expressed political unity will help us achieve broader support for ecological restoration and the enrichment of tribal cultures. In addition, as individual tribal buffalo programs emerge it can inspire a national agenda to attempt what once seemed unlikely for an oppressed people.

We call on the public, federal and state natural resource agencies, and the conservation community to support our intentions and help return iiniiwa to its rightful place in prairie ecosystems and native cultures.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.

Most Popular