'Dr. Mütter's Marvels' (US 2014): Book Excerpt

Cristin O'Keefe Aptowicz contributed this excerpt to Live Science's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

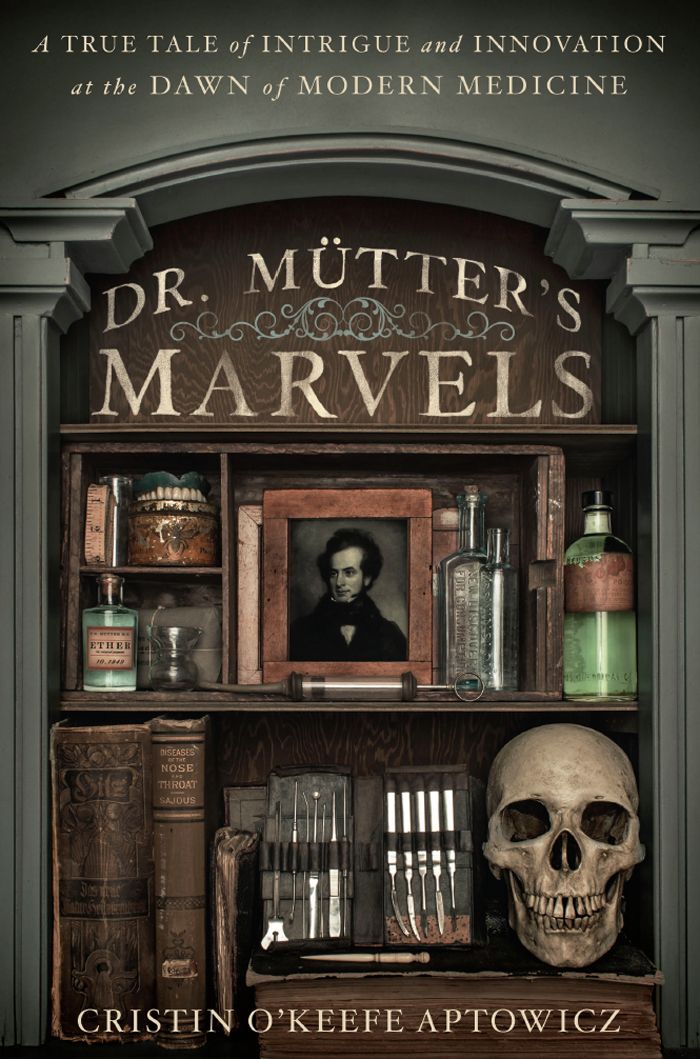

In the 19th-century, doctor Thomas Dent Mütter (1811-1859) made a name for himself as a young surgeon specializing in performing reconstructive surgery on the severely deformed in a time before anesthesia. In the new book, "Dr Mütter's Marvels: A True Tale of Intrigue and Innovation at the Dawn of Modern Medicine" (Gotham Books, 2014), author Cristin O'Keefe Aptowicz explores the life and times of this idiosyncratic doctor and American original. The following is an excerpt from the book.

Read more about Dr. Mütter in "Anesthesia's Evolution: Satanic Influence to Saving Grace (Op-Ed )" and see examples of his medical imagery and his specimen collection in The Macabre Dr. Mutter's Freaky Medical Marvels .

Reprinted by arrangement with Gotham Books, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, A Penguin Random House Company. Copyright © Cristin O'Keefe Aptowicz, 2014.

Excerpt:

"Dr Mütter's Marvels: A True Tale of Intrigue and Innovation at the Dawn of Modern Medicine"

Chapter One: Monsters

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Mütter knew that surgery was his calling, and raced through the streets of Paris to study the work of its greatest practitioners. He was aggressive in his pursuits, pushing through crowds to secure the best seats at the surgical lectures, or firmly staying as close as possible to the lecturing doctors as they made their rounds in hospital, no matter how much the other students pushed. Meals of spiced mutton and fresh bread went half-finished as he plotted the next week's schedule. Bowls of café au lait were abandoned so he could make an early start every morning, eager to begin his day.

He had come to Paris assuming it would be the doctors themselves who would have the greatest influence on him, these men who were legends in their own time. Chief among them was Guillaume Dupuytren, who ruled over the Hôtel-Dieu, the city's largest hospital, and single-handedly changed how surgery was done. An immensely brilliant operator, exhibiting marvelous dexterity, proceeding with almost inconceivable speed, his boorish arrogance became as famous as his accomplishments in the surgical room. Jacques Lisfranc de St. Martin was head of the Hôpital de la Pitié, the city's second-largest hospital. He was Dupuytren's greatest friend turned into his most bitter rival, and spent most of his life trying to escape Dupuytren's shadow. Lisfranc was known to refer to Dupuytren as "the bandit of the river bank," while Dupuytren frequently called Lisfranc "that man with the face of an ape and the heart of a crouching dog." There was Philibert Joseph Roux — who so dazzled his classes with his graceful and brilliant work that it was said "his operations were the poetry of surgery," but who had also earned Dupuytren's scorn years earlier by winning the hand of the woman they both loved. And Alfred-Armand-Louis-Marie Velpeau, whose textbook on obstetrics was so influential, it had been translated into English by one of America's most respected obstetricians: Philadelphia's own Charles D. Meigs.

Mütter was deeply impressed with the audacity of each of these surgeons' talents and their seemingly inexhaustible work ethic. However, it was not any single man who ended up changing the course of Mütter's life but, rather, a new field of surgery freshly emerging in Paris, which even the French referred to as la chirurgie radicale.

Who sought out this radical surgery?

Monsters. This is how the patients would have been categorized in America. Mütter was used to seeing them replicated in wax for classroom display, or hidden in back rooms away from the public eye. He had seen them in jars, fetuses expelled from their mothers, irreparably damaged. Monster, the label would read.

Some of these monsters were born that way: A cleft palate so severe the face looked to have been split in two with an ax. Hardly able to eat or drink, spit collected in pools on the child's clothing as his tongue lolled around the open hole of his mouth, awkward and exposed.

Others were born "normal," but their bodies would slowly turn them into monsters, as tumors laid siege to their torsos or limbs, swelling their legs like soaked wood, their eyes strained and nearly popping.

Other times, the monsters were man-made: Men whose noses were cut off in battle, or as punishment, or for revenge, the centers of their faces evolving into a large weeping sore; women whose dresses caught fire, becoming houses of flames from which their owners couldn't escape, the skin on their faces turned into melted wax, their mouths permanently frozen in screams.

Monsters. This is what they were called, and this was how they were treated. For such tortured people, death was often seen as a blessing.

In Paris, however, the surgeons had a solution. They called it les operations plastiques.

Was it quackery? Mütter wondered when he first heard about it. Was it a trick? Would these unfortunates be presented like a sideshow? Were the doctors in the audience there to learn or to gape? What could surgeons possibly do to help such hopeless cases?

At the very first lecture, Mütter began to understand the difference between regular surgery and les opérations plastiques.

The patient, often greeted with gasps of horror and pity, stood stock-still and unafraid as the surgeon made his examination. These regrettables didn't show the unease normal patients did; their eyes didn't wander back to the door from which they entered and through which they could also escape. Gradually, Mütter grew to understand why.

In regular surgical lectures, patients rarely understood the trouble they were in. When the knife first pierced the skin, they could come to the sudden realization that a life without this surgery might still be a happy one. Thus, escape was the best possible solution and a choice they wanted to exercise right away.

Patients of les opérations plastiques, however, were often too aware of their lot in life: that of a monster. It was inescapable. They hid their faces when walking down the street. They took cover in back rooms, excused themselves when there were knocks at the door. They saw how children howled at the sight of them. They understood the half a life they were condemned to live and the envy they couldn't help but feel toward others — whole people who didn't realize how lucky they were to wear the label human.

It was not uncommon for these patients to enter the surgical room fully prepared to die. Death was a risk they happily took for the chance to bring some level of peace and normality to their mangled faces or agonized bodies. The surgeries weren't physically necessary to save their lives; rather, they were done so the patient might have the gift of living a better, normal life. That is what les opérations plastiques promised.

Plastique was a French adjective that translated to "easily shaped or molded." That was the hope with this surgery: To reconstruct or repair parts of the body by primarily using materials from the patient's own body, such as tissue, skin, or bone.

The surgeries, of course, were not always successful — if a patient's problem had been so easy to fix, it would have been corrected by lesser doctors years ago. But other times — and these were the times the audience waited for, the ones that made Mütter's hair stand on edge — the end result was nothing short of miraculous.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Live Science.