How Caffeinated Energy Drink Triggered Teen's Heart Problem

For a teenage boy in England, drinking one highly caffeinated beverage at the gym set off a heart problem he didn't know he had, according to a new report of his case.

The boy's heart began racing, so the 17-year-old went to the emergency room, but his cardiovascular exam looked normal, as did a chest X-ray and routine blood tests. Doctors gave him drugs to slow his heart rate, but the medications instead caused his blood pressure to drop and led to a state called atrial fibrillation, making his heartbeat irregular and chaotic.

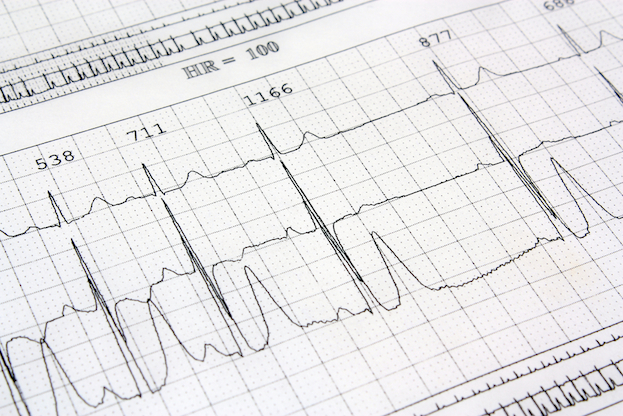

A cardiologist then gave the teenager an electric shock, which dramatically improved the boy's symptoms and blood pressure. And an electrocardiogram (EKG) revealed the problem: there was an extra electrical circuit in the boy's heart. [Heart of the Matter: 7 Things to Know About Your Ticker]

The human heart typically has one electrical pathway, and the impulses travel along it through the organ's center from its top to its bottom. But in people with a condition called Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome, the heart also has another electrical connection, along its side.

This extra circuit stimulates the heart "in a way that is not the normal pattern," said Dr. Nicholas Skipitaris, the director of electrophysiology at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, who was not involved in the boy's case.

Symptoms of the condition include light-headedness, dizziness or feeling faint, but the most common sign is rapid heartbeat. "People can say, 'My heart is beating out of my chest," or 'I feel my heart beating in my throat,'" Skipitaris told Live Science.

In some people, the extra circuit is so weak that the condition doesn't cause any real problems. People who do have problems usually discover they have the condition during adolescence, and have it treated before adulthood, Skipitaris said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The extra pathway means that the heart muscle may not always contract downward as it should, and push blood from the upper chambers toward the lower chambers. "It can conduct upward too, from the lower chambers back up," said Dr. Mohan Viswanathan, a cardiologist with Stanford University’s Cardiovascular Medicine Clinic, who was also not involved in the case.

People with WPW syndrome often don't show symptoms, but stimulants can easily drive up their heart rate. In the boy's case, the energy drink likely caused the heart palpitations, but the condition can also be triggered by dehydration, weight loss drugs that increase adrenaline or taking cocaine, Viswanathan said.

About 1 to 3 people per 1,000 people have the syndrome. Less than 0.6 percent of people with the syndrome are at risk of sudden cardiac death, the study reported.

After learning that he had WPW syndrome, the teenager underwent several electrophysiological studies and then surgery to turn off the extra circuit in his heart.

"It's like taking a wire you don't want to function anymore, and cutting it so the wire can no longer conduct electricity," Skipitaris said.

In the 1960s and 1970s, people with WPW syndrome underwent open-heart surgery. These days, the procedure is less risky, and involves slipping a thin tube called a catheter into the heart through a vein in the groin. The catheter delivers radio frequency waves that deaden or cauterize the area with heat, Viswanathan said.

"It usually takes less than 20 seconds once we get to the right spot," Viswanathan said. "Low and behold, the moment it's gone, the EKG changes into a normal EKG."

The study was published Wednesday (Sept. 24) in the journal BMJ Case Reports.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.