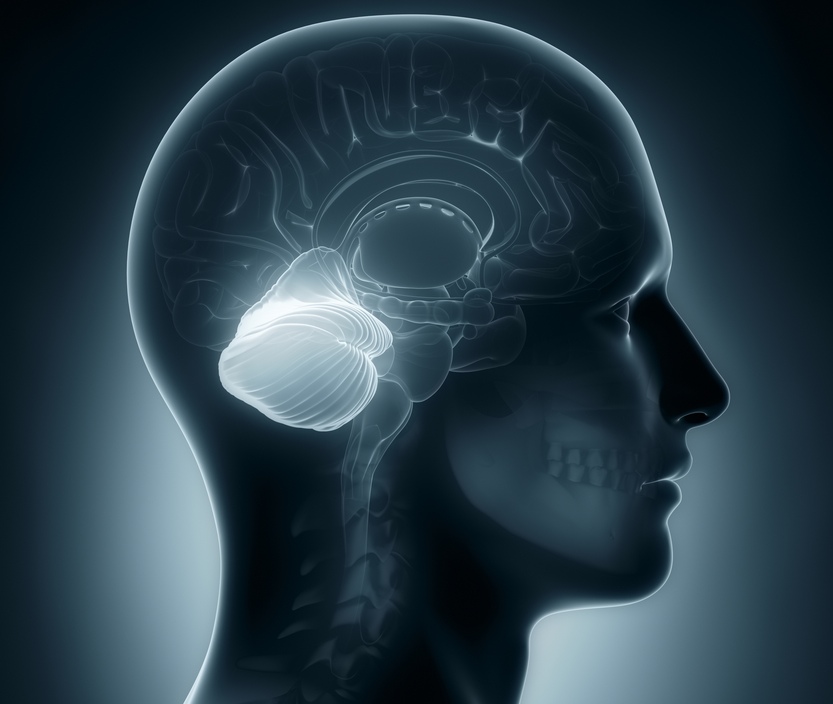

Does the Brain's Cerebellum Make Humans Special?

The brains of apes and humans evolved unusually quickly when it came to the cerebellum, a part of the brain involved in control of movement, researchers say.

The finding may change what is considered special about the human brain, scientists added.

The unique mental abilities of humans are usually attributed to the cerebral cortex, which encompasses about three-quarters of the human brain's mass. The largest part of the human cerebral cortex is the neocortex, which is thought to be key to conscious thought, sensory perception and language.

However, the cerebellum holds four times more neurons than the neocortex, suggesting the way it changed over time may have played an important role in human evolution as well. [The Top 10 Things That Make Humans Special]

"Our earlier work showed that evolutionary expansion of the cortex and the cerebellum were intimately linked in mammalian evolution — when one changes, so does the other," said lead study author Robert Barton, an evolutionary biologist at Durham University in England.

Prior research suggests that besides controlling movements, the human cerebellum may also be linked to a much wider range of complex mental functions than thought.

"In humans, the cerebellum contains about 70 billion neurons," Barton said in a statement. "Nobody really knows what all these neurons are for, but they must be doing something important."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The expanding brain

To see how much the human cerebellum evolved, scientists investigated how the cerebellum and other parts of the brain differed in size among humans, apes and monkeys. They also compared the timings of when the ancestors of humans diverged from various ancestors of apes and monkeys. For instance, humans last shared common ancestors with chimps and bonobos about 6.2 million years ago; with gorillas, about 8.7 million years ago; with orangutans, about 15.1 million years ago; and with gibbons, about 19.6 million years ago, said study co-author Chris Venditti, of the University of Reading in England. Using this technique, the researchers were able to estimate how fast each part of the brain expanded during the evolution of humans, apes and monkeys.

The researchers discovered the cerebellum expanded up to six times faster in apes, including humans, than anticipated when looking at how other regions of the brain changed.

"The relative expansion of the cerebellum in apes means that the human brain contains 16 billion more cerebellar neurons than would a monkey brain that was scaled up to be the same size," Barton told Live Science. Coincidentally, "it so happens that 16 billion is the number of neurons found in the entire human cortex."

These findings "turn the story of brain evolution upside down," Barton said. While the majority of research may have assumed the most interesting parts of human brain evolution took place with the cerebral cortex, "our new study shows that a structure traditionally associated with the control of movement has been more important than people realized," Barton said.

What triggered our big brains?

Since the acceleration of cerebellum size expansion started at the origin of the apes, the researchers suggest the initial trigger for this change may have been how large primates had to travel below branches in forests. [Image Gallery: Our Closest Human Ancestor]

"Large-bodied apes cannot run along the branches or leap between small branches, so they need to be more circumspect and plan their routes," Barton said. The need to devise and execute complex routes through forest canopies may have "kickstarted the evolution of ape intelligence," he said.

The scientists noted recent studies hint that the cerebellum is especially involved in the organization of complex sequences of behavior, "such as those involved in making and using tools," Barton said. "The ability to flexibly organize behavioral acts into complex sequences is obviously critical to human technology. It is also presumably something that underpins our ability to speak in complicated sentences, and evidence is now emerging from other studies for a critical role of the cerebellum in language."

The changes in the cerebellum may therefore have supported humanity's technical intelligence. These findings may "shift attention away from an almost exclusive focus on the neocortex as the seat of our humanity," Barton said in a statement.

"We are not saying, 'Forget about the role of the cortex' — just that we should pay more attention to the cerebellum," Barton stressed. "There was a shift in the pattern of brain evolution at the origin of the apes, which places more emphasis on the cerebellum as a crucial structure for the processes that make apes — including humans — cognitively distinct."

Barton noted some other species, particularly elephants, have a very large cerebellum. Future research could investigate whether this similarity could represent an example of evolution converging on similar mental abilities, he said.

Barton and Venditti detailed their findings online today (Oct. 2) in the journal Current Biology.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.