52-Million-Year-Old 'Ant-Loving' Beetle Caught in Amber

A newly discovered 52-million-year-old fossil of an "ant-loving" beetle is the oldest example of its species on record, and may help researchers learn more about this social parasite, a new study finds.

Like its descendants living today, the ancient beetle was likely a myrmecophile, a species that depends on ants for survival. The prehistoric beetle probably shared living quarters with ants and benefited from their hard work by eating ant eggs and taking the ants' resources.

Other myrmecophiles include the lycaenid butterfly, which lays its eggs in carpenter ants' nests, tricking the ants into caring for their young; and the paussine ground beetle, which also dupes ants by living alongside them as it preys on the ants' young and workers. [The 10 Most Diabolical and Disgusting Parasites]

The beetles' and butterflies' shared parasitic behavior suggests that myrmecophily (ant love) is an ancient evolutionary phenomenon, the researchers said. But the fossil record of such creatures is poor, making it unclear how and when this practice arose, they added.

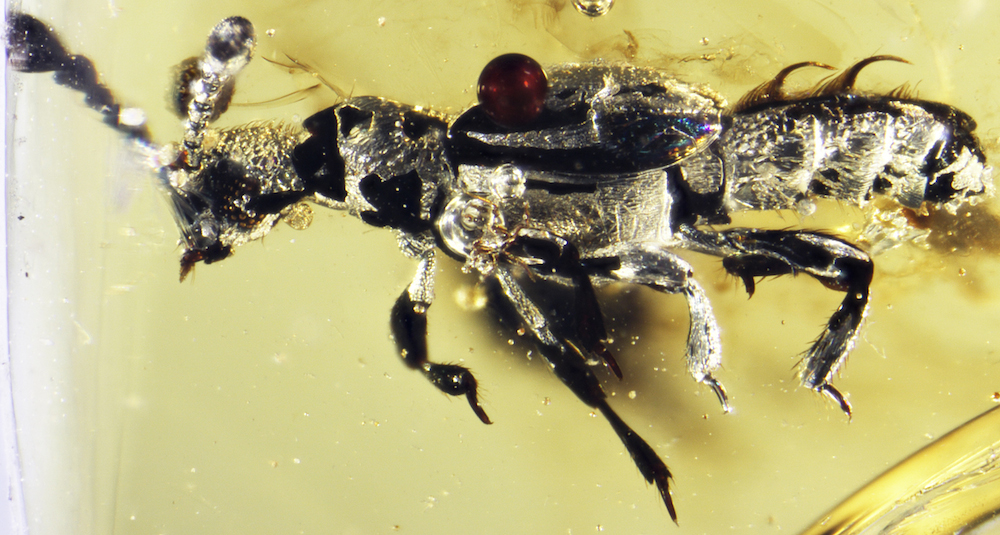

The amber-encased beetle, now known as Protoclaviger trichodens, and other stealth beetles began to diversify just as modern ants became more abundant in prehistoric times, the researchers found.

"Although ants are an integral part of most terrestrial ecosystems today, at the time that this beetle was walking the Earth, ants were just beginning to take off, and these beetles were right there inside the ant colonies, deceiving them and exploiting them," beetle specialist and lead researcher Joseph Parker, a research associate at the American Museum of Natural History and postdoctoral researcher at Columbia University, said in a statement.

There are roughly 370 known beetle species that belong to the Clavigeritae group, myrmecophiles that are about 0.04 to 0.12 inches (1 to 3 millimeters) long. But many more myrmecophile beetles are likely awaiting discovery, Parker said."This tells us something not just about the beetles, but also about the ants — their nests were big enough and resource-rich enough to be worthy of exploitation by these super-specialized insects," Parker explained. "And when ants exploded ecologically and began to dominate, these beetles exploded with them."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sneaky beetles

The beetles use a sneaky strategy to bypass the high security surrounding ant nests. Ants rely on pheromones to recognize intruders, which they then dismember and eat. In a feat that continues to mystify scientists, Clavigeritae beetles are able to pass through this smelling system and participate in colony life. [Mind Control: See Photos of Zombie Ants]

"Adopting this lifestyle brings lots of benefits," Parker said. "These beetles live in a climate-controlled nest that is well protected against predators, and they have access to a great deal of food, including the ants' eggs and brood, and most remarkably, liquid food regurgitated directly to their mouths by the worker ants themselves."

The beetles have evolved to look a certain way to reap these benefits, he said.

Clavigeritae beetles look nothing like their close relatives. The segments within their abdomens and antennas are fused, likely to provide protection against worker ants, which are somehow tricked into carrying the beetles around the nest. Eventually, the worker ants carry the beetles to the brood galleries, where the beetles feast on eggs and larvae, Parker said.

The beetles also have recessed mouthparts, which make it easy for them to receive liquid food from worker ants. They also coat their bodies with oily secretions from brushlike glands that may encourage the ants to "adopt" them, in lieu of attacking them. But the chemical makeup of these secretions is unknown.

"If you watch one of these beetles interact inside an ant colony, you'll see the ants running up to it and licking those brushlike structures," Parker said.

Rare beetle find

Yet it's rare to encounter Clavigeritae beetles in the wild, making the new specimen — which is possibly the first fossil of this group to be uncovered — a valuable find.

Researchers named it Protoclaviger trichodens, from the Greek word prótos ("first") and claviger ("club bearer"). To describe its tufts of hair, the research team used the Greek word tríchas ("hair") and the Latin word dens ("prong").

The fossil, from the Eocene epoch (about 56 million years ago to 34 million years ago), is an amber deposit from what was once a rich rainforest in India. The body may look like that of modern Clavigeritae beetles, but two hooklike brushes on top of its abdomen, called trichomes, give it a primitive appearance, the researchers said. Also, Protoclaviger's abdominal segments are still separate, unlike the fused-together segments in today's beetles.

"Protoclaviger is a truly transitional fossil," Parker said. "It marks a big step along the pathway that led to the highly modified social parasites we see today, and it helps us figure out the sequence of events that led to this sophisticated morphology."

The study was published today (Oct. 2) in the journal Current Biology.

Follow Laura Geggel on Twitter @LauraGeggel and Google+. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Laura is the archaeology and Life's Little Mysteries editor at Live Science. She also reports on general science, including paleontology. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and a master's degree in science writing from NYU.